"Don't waste your time", the editor of a new magazine about television advised me. "We went to the old guy's house and just could not get him to focus. All he talked about was his place in Florida".

It was 1981, and the publication's debut issue noted that Vladimir Zworykin, known as "The Father of Television", was nearly 92 years old and living in Princeton, New Jersey, near the RCA Laboratories where he had served as director.

Despite the warning, I asked for Zworykin's phone number. At the time, I had successfully interviewed quite a few extremely old folks for the two radio stations where I was news director, and I was fairly certain the drive from New York City to Princeton would be worth it.

My conversation with Dr. Zworykin turned out to be one of the most memorable of my career, and I was reminded of it when I heard that the Television Academy Hall of Fame would be posthumously inducting Philo T. Farnsworth on March 11. On its website, the Academy refers to Farnsworth as "The Forgotten Father of Television", adding "the first crude television image was created from the Farnsworth system when a photograph of a young woman was transmitted... on September 7, 1927."

The debate over just who gets credit for the device that changed the world began in the 1920s and continues to this day. A play by Aaron Sorkin about the dispute made it to Broadway in 2007, and a popular video game created in 2011 called "Iron Brigade" features a character ironically named "Vladimir Farnsworth". Zworykin himself modestly said he was just one of hundreds of scientists involved.

Despite the fuzzy and complex history of TV's creation, it seems reasonable to say that the contributions of both Farnsworth and Zworykin were key to the development of electronic television. And when I arrived at Zworykin's tree-shaded home in Princeton on a warm July day in 1981, I let him tell the story.

Born on July 30, 1889 in a town a couple of hundred miles from Moscow, Zworykin recalled a pivotal moment in his childhood. His father owned a fleet of boats, and at age five, the captain of one of the vessels was showing him around.

"He took me on the top of the boat, and he pressed a button", Zworykin recalled in his thick Russian accent. "I heard some buzz from the bottom, in answer from the mechanic. That impressed me. Of course, I asked permission from the captain... and I pressed the button. That's the first time I touched an electrical appliance", he said with a chuckle, thinking back to that day in 1894.

"He took me on the top of the boat, and he pressed a button", Zworykin recalled in his thick Russian accent. "I heard some buzz from the bottom, in answer from the mechanic. That impressed me. Of course, I asked permission from the captain... and I pressed the button. That's the first time I touched an electrical appliance", he said with a chuckle, thinking back to that day in 1894.

In 1912, the young man earned a degree in electrical engineering, having studied with a pioneer of cathode ray tube technology, Professor Boris Rosing. He continued his education in Paris, then worked with radio in the Russian army during World War I. In 1919, he emigrated to the U.S. and soon was employed by the Westinghouse corporation.

It was there that Zworykin concentrated on the iconoscope camera tube, which, along with kinescope picture tube, laid the foundation for the first non-mechanical television system. I had read about the comment made by a Westinghouse executive who came to see what this Russian immigrant was up to, and asked the scientist to tell me the now-legendary anecdote.

"The first demonstration (of television) was in September of 1923, for the director of Westinghouse", Zworykin said. "Picture was very simple, but I was able to show from the window of my laboratory the boats going by, and that produced a very big impression on me. Finally, I succeeded to make the tube on which you can reproduce the moving picture".

But the director muttered something to Zworykin's immediate supervisor and left the room. "The moment he left, I come to my boss and said 'What did he say?' He said (to my boss), 'Will you put this guy to work on something more important?!'" Nearly 60 years later, Zworykin laughed at the memory.

We were sitting in a small parlor on the first floor of Zworykin's home for the interview. I had closed the doors to the room, saying it needed to be quiet, as this was being recorded for radio, but the real reason was to avoid any distractions. The ploy worked well, and we spoke at length about his more than 120 patents for devices ranging from the electron microscope to electronically-controlled missiles to radiation detectors.

And then we returned to the subject of television. "Let me ask you a simple question", I said. "Do you watch it?" Zworykin's face turned somber as he replied. "Frankly, no. The technique is wonderful. I didn't ever dream it would be so good, the color and everything. It is beyond my expectations".

Suddenly, the frail old man's voice became loud and strong, as he continued. "But the programs! I would never let my children even come close to this thing! It's awful what they're doing!"

"What's wrong?" I asked. "What should they be doing?" "First", he said, wagging his finger, "they have to remove the majority of the sex pictures!" Settling back a bit in his chair, he added, in a softer voice, "Probably they're making a lot of money".

The remark, reported a couple of weeks later by UPI on Zworykin's 92nd birthday, made headlines. The New York Times wrote "TV Turns Off Its Father", and the audio version was broadcast coast to coast.

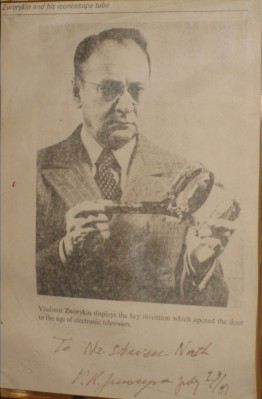

I concluded the interview, which turned out to be his last, by speaking with Zworykin about the 27 major awards he'd received, including the National Medal of Science, the nation's highest scientific honor. I took one photo of him gazing at all the plaques and statuettes, and another of him holding a replica of the iconoscope.

Then I asked how he'd like history to remember him. "Personally, I not care. I'm very flattered. But I wouldn't work for that (recognition) only. I worked for 70 years in television."

Zworykin passed away the next year. More than three decades later, I often think of him as I watch my 52-inch flat-screen HDTV, imagining what his reaction would be to both the technology and the content. And I'm always grateful that he ignored the advice of that executive who, back in 1923, couldn't realize the significance of those blurry images on that flickering screen.

Steve North is a broadcast journalist with CBS News.