Iranians have been protesting for centuries -- if you could read Persian, you'd know.

They are a nation with a keen sense of their rights, and an audacity to speak up for themselves, whether it's in the streets, on the page or on the web.

They are also a nation that has never had a truly representative government and thus has adapted its discourse to the guile and euphemism which are required to express thoughts -- political in nature -- which could otherwise tempt misfortune.

Double entendres, metaphors and symbolism are a part of the gift of "gap" (the Persian word for "gab") so it is no wonder that literature holds such an eminent position in Iranian culture.

For centuries, poetry in particular has been the ultimate form of expression for Iranians: Iranian poetry is a manual for life and thought, a centuries-old avenue for political dissent.

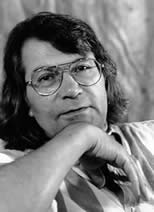

"In its essence, literature is not tied to politics. If literature has any duty, it is a commitment to language and the creation of beauty," says Esmail Kho'i, Iran's pre-eminent poet philosopher, "however in certain circumstances, writers and poets become forced to give rise to politics. The reality is that they do not seek politics, it is politics which obliges them."

Kho'i leads the pack of Iranian poets who have turned to their craft to protest not merely a disputed election, but a system of government which for 30 years has mandated a life of religious fundamentalism for a nation which doesn't exactly like being told what to do.

"Today's Iran is the victim of one of the ugliest, most anti-human, most anti-culture, most anti-woman, most anti-beauty, most anti-smiling, most anti-happiness, most anti-everything systems of government in its entire history," Kho'i says.

The poet -- bright, sensitive -- captures the collective anger and pain of three decades of holy governance and the fear and inhumanity which has become its legacy. Kho'i's newest collection of poetry includes the poem "Elegy for Mousavi", a conversation with Mir Hossein Mousavi, the presidential candidate whose loss in the disputed election sparked the initial protests.

Mr. Mousavi, if you hear me, you will never forget

The blood of Neda, Bahman, and Ashkan

With deception and sedition, the Ayatollah advanced his workNow, you must move past this sedition

Now is the time to choose, and nothing elseWoe be upon you should you take it lightly

The Republic and the Caliphate are as water and fireThe presence of one will eliminate the other

Esmail Kho'i

Esmail Kho'i

In the wake of this summer's anti-government protests in Iran, poetry in particular has again stepped into its comfortable role as a purveyor of political dissent for Iranians. Poet Mahnaz Badihian runs Mahmag.org, a multilingual (English, Persian, Spanish and Italian) literary web magazine which derives much of its Persian-language content from unsolicited literature from within Iran.

"We've always received much attention from Iranians in the country -- they are extremely passionate about having their voices heard," Badihian says, "but since the election, the number of submissions has significantly increased." The poets and writers, she says, are doing what they have done for years now: "escaping the void of censorship and fear to express their deepest emotions, experiences, and thoughts."

Badihian's own poetry has reflected the solidarity that many Iranians abroad feel with their fellow ham-vatanis (literally: same-nationers) and their courageous efforts to protest against the system of government. In her poem "The Rooftoppers," she reflects on the reports of the thousands of Iranians who have regularly taken to their rooftops at night to perpetuate the protests beyond dusk -- at the risk of having their homes invaded by security forces.

Our home is possessed

At night we turn to our rooftop

From rooftop to rooftop we protest

Asking ferociously: where is the compassionate God

Our voice echoes with the wind, blow dear courageous wind

Our voice grows taller than poplar trees, so together we stand

Up there, our naked souls together invent bravery, in the moonlight

From rooftop to rooftop we go, till the gaze of morning glories calls us

Up there, again we ask ourselves: who measured God on the rooftops

But we know up there the hands of fear are bigger than the eyes of truth

For poets like Badihian and Kho'i the inescapable necessity of engaging with politics is beyond the control of any Iranian writer or poet. "For Iranians anywhere they live right now, their heart and thoughts are with what is happening in Iran right now," Badihian says, "for poets and writers in particular, our reply to the painful memories of the past decades and the continuing pain of today is expressed in the way we weave our words."

When all else fails, even silence is a defiant statement in Iranian literature. "The power of silence and the intentional refusal to take pen to paper can be a political act," Kho'i says. Poets and writers, Kho'i contends, can also be paralyzingly overwhelmed by the troubles in Iran.

"When Khomeini says Islam governs a human being from before he or she is born until long after he or she dies, this means we are faced with a system of government which even in our place of rest, or in our hospital room, or in our bed, or in the toilet concerns itself with governing its citizenry," Kho'i says, "then even lovemaking becomes a political act. Even going to the toilet becomes a political act. In such circumstances, anything you do or don't do is political."

There is an old saying in Persian, that every Iranian has written at least one line of poetry in their lifetime -- one can only imagine how many millions of lines have been written this summer alone.