A good night’s sleep in Waikiki is hard to come by for Roberta Huddy.

She became homeless about a year ago after losing her job as a guest services agent at one of the hotels.

Now Huddy, who was born and raised on Kauai, lives in a worn-down Chevy Astro with her husband, Greg, on Kalakaua Avenue next to Kapiolani Park. Their few belongings fill the vehicle from the passenger seat to the back hatch, blankets on the floor serving as a makeshift bed. The van is also their getaway vehicle. It allows them to avoid police and city park crews who have ramped up their efforts to clear the homeless out of Waikiki.

Like many others who live on the streets, the Huddys are on the run.

Roberta Huddy, 50, has lived in her van with her husband for about a year. They are constantly moving to avoid harassment and ticketing by the police.

Roberta Huddy, 50, has lived in her van with her husband for about a year. They are constantly moving to avoid harassment and ticketing by the police.

“All they say is that we should move around,” Huddy complained while perched on the edge of her Astro. “At night I like to go up to Kapahulu because at least there I can sleep in peace.”

An estimated 4,700 homeless people live on Oahu, 1,600 of them without any shelter. Those figures give Honolulu the dubious distinction of having one of the highest per capita rates of homelessness in the country.

By choosing to live in Waikiki, the Huddys and others are on the front lines of a campaign to combat homelessness in the tourist mecca. And lately, they’re part of a nightly migration resulting from city efforts to enforce park closure hours and other ordinances to keep the sidewalks clean.

Those efforts take two basic forms: occasional major sweeps that can result in dozens of arrests, and nightly visitations that drive the homeless from the streets for a few hours when even the most energetic tourists are asleep in their hotel beds.

‘Looks So Much Better’Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell said at a June 4 press conference that this approach has made a difference, particularly in Waikiki. The mayor lauded the efforts of the patrol crews, and said that on a recent trip to Waikiki he was approached by several people who had noticed the improvement.

“Police officers came up to me and said it looks much better,” Caldwell said. “Residents who live there came up to me and said, ‘Mayor, what are you doing? It looks so much better.’”

But the reality is — and Caldwell acknowledged this during the press conference — that Honolulu’s homeless aren’t moving indoors. They’re bouncing from sidewalk to sidewalk and park to park.

That’s because not everyone who’s rousted wants to go to a shelter, and the city doesn’t have permanent housing options for the homeless, which is the backbone of Caldwell’s Housing First initiative. And while the Honolulu City Council recently budgeted nearly $50 million to help build more housing for the homeless, the worry is that it will take years to do that.

“We need to do things quickly at this point, particularly in certain communities like Waikiki and Chinatown and on the Leeward Coast,” Caldwell said. “People are saying you need to act. We don’t have two or three years to see results. We need to see results next week, and I’m anxious to do exactly that.”

Among the bin and bags, a shirtless man sleeps directly on the sidewalk next to a planter on Kalakaua Avenue on June 9.

Among the bin and bags, a shirtless man sleeps directly on the sidewalk next to a planter on Kalakaua Avenue on June 9.

Feeling HelplessBut are the nightly sweeps effective when housing for the homeless is scarce?

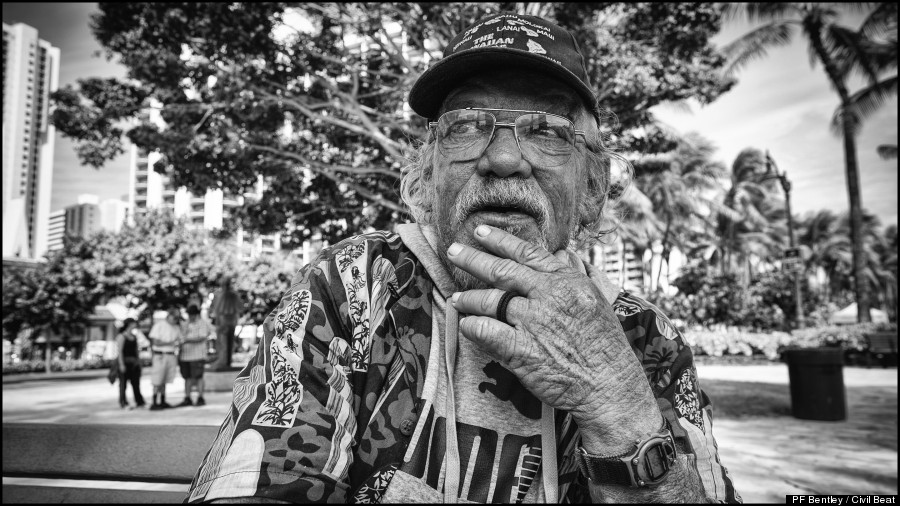

Bill Warren, 62, has had his tent and many of his clothes seized by city crews. He can’t afford to pay $200 to get his belongings out of municipal storage once they’ve been taken. He’s watched as city crews threw some of his belongings, including those that held his identification and other important materials, into the trash.

“Only ID I got is a bus pass with my picture on it,” Warren said.

Bill Warren, 62, said he has had some of his property confiscated and thrown in the trash.

Bill Warren, 62, said he has had some of his property confiscated and thrown in the trash.

He wants to move back inside, and perhaps even rent an apartment in Waikiki using his monthly disability payments. But like many others in his predicament he’s battling addiction and mental illness.

“I don’t know exactly what I’m going to do,” Warren said. “I’ve got depression, some anxiety and, of course, a drinking problem. That’s three strikes.”

It’s clear the sweeps — which cost about $15,000 each — are having an effect. Many who are living on the streets are becoming weary and upset.

Devin Goodwin came to Honolulu about six months ago. The 21-year-old was couch surfing in Alaska and spent the last of his money to fly to Hawaii. The first bus he hopped on from the airport brought him to Waikiki, where he panhandles with his friends, holding signs that say things like “Smile if you masturbate” and “My girlfriend thinks I’m ugly. Need money to get her drunk.”

Goodwin says he’s been caught up in at least two of the recent police sweeps and has also been arrested, once for selling marijuana and another time on a bench warrant for not showing up to court.

“We’re losing all our stuff,” Goodwin said. “It’s making other people leave.”

Devin Goodwin, 21, came from Alaska. The airport bus dropped him off in Waikiki five months ago and he’s been living on the streets since.

Devin Goodwin, 21, came from Alaska. The airport bus dropped him off in Waikiki five months ago and he’s been living on the streets since.

A homeless man walks out of park at 12:02 a.m. to avoid police who have been patrolling the park areas every night. He will be walking to another area of Honolulu for the night out of the boundaries of Waikiki.

A homeless man walks out of park at 12:02 a.m. to avoid police who have been patrolling the park areas every night. He will be walking to another area of Honolulu for the night out of the boundaries of Waikiki.

Goodwin says he doesn’t plan to abandon his life on the streets of Waikiki, and feels he should stand up to the authorities who “steal” from the homeless.

But at the same time he realizes he’s powerless so long as he chooses to live outdoors.

“What am I going to do?” Goodwin asked, arms outstretched as he watched people pass by on Kalakaua Avenue. “They’re tourists spending money. I’m homeless.”

Goodwin doesn’t want to go to a shelter. For one thing, he has a dog, Angel, that might not be allowed in. And like many others, Goodwin doesn’t trust that moving into a shelter is a better option.

Bed bugs are a concern. And some people living on the streets say that putting the homeless into such close proximity can lead to violence, theft and even rape.

Necessities of LifeLife is not getting easier for Honolulu’s homeless, especially those living in Waikiki where the tourism industry has put immense pressure on Caldwell and others to clean up the streets.

Even before the latest sweeps, the mayor had vowed to ramp up the city’s enforcement efforts as part of his “war on homelessness.” Police have been making dozens of arrests in areas such as Waikiki and Chinatown.

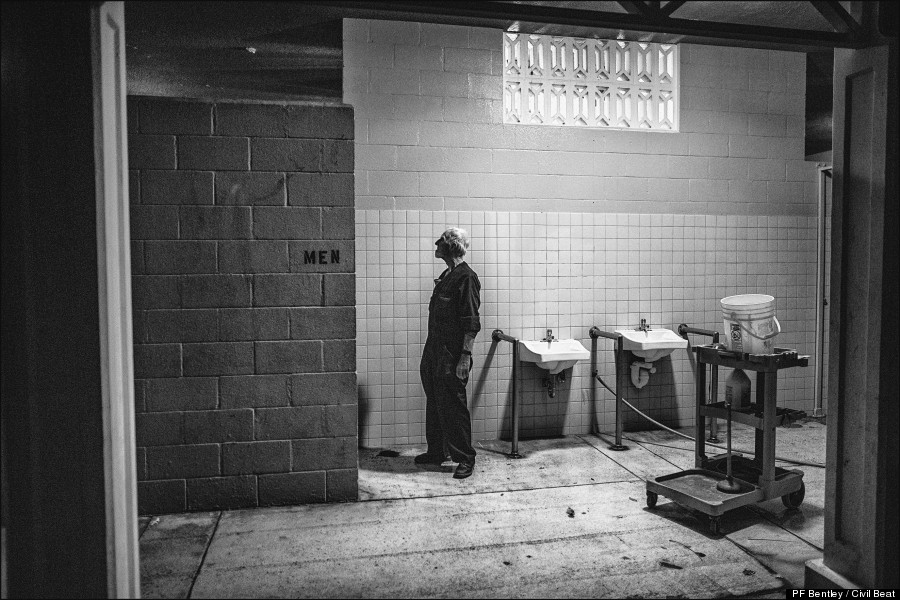

A homeless man checks a locked door on a public restroom at 9:10 p.m. in Waikiki. The restrooms are supposed to be open until 10 p.m.

A homeless man checks a locked door on a public restroom at 9:10 p.m. in Waikiki. The restrooms are supposed to be open until 10 p.m.

Caldwell also wants to enact new laws to give the police more authority to move Hawaii’s homeless off the streets. One idea he pitched is a new ordinance that would prohibit sitting and lying on public sidewalks.

The city is shutting down Waikiki’s public bathrooms early to make life on the streets a bit more difficult.

Candace Hilton said she’s fed up with the constant badgering, and claims the city is violating her rights.

Hilton is in her 60s. Her weathered face and rotted teeth tell their own story about a life without daily hygiene.

What few possessions Hilton had are gone. She used to spend her days knitting and crocheting as a way to help raise money for food. But her knitting needles and scissors were taken during a recent sweep.

A man passed out on a park bench along Kalakaua Avenue at 12:33 a.m. He did not awaken when the sprinklers were turned on.

A man passed out on a park bench along Kalakaua Avenue at 12:33 a.m. He did not awaken when the sprinklers were turned on.

Her only real source of income now, she says, is scavenging for recyclables left behind in the garbage cans lining Kalakaua.

“Quite frankly this is messing me up so badly,” Hilton said. “So much of what these laws revolve around are the basic necessities of life.”

But even the city’s disruption tactics haven’t been enough to change everyone’s mind about living in Waikiki. Each day the homeless come back. And as Huddy explained, their reasons are simple.

“It’s convenient, it has showers and bathrooms and water,” she said. “I like to bathe every day and use the bathroom when I want to.”

“I love the beach too,” she added. “That’s why I keep coming here.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Roberta Huddy owned a Ford Astro. The Huddy's own a Chevy Astro.

Nick Grube is a reporter for Honolulu Civil Beat. You can reach him by email at nick@civilbeat.com or follow him on Twitter at @nickgrube.