Walgreens just rocked the boat for companies fleeing U.S. soil to avoid paying taxes.

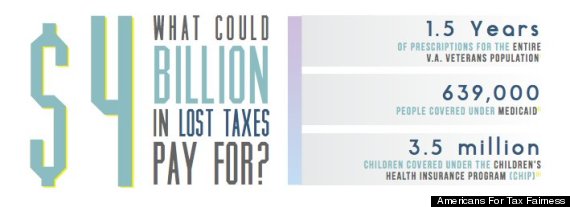

Walgreen Co., the drugstore chain's parent company, announced Wednesday that it would not move its headquarters to Switzerland to take advantage of its relatively low corporate tax rates after the company completes a purchase of European rival Alliance Boots. Such a move might have cost U.S. taxpayers $4 billion over five years, according to a report by the nonprofit group Americans For Tax Fairness and the labor group Change To Win.

Walgreen's decision bucks a growing trend of "tax inversions" -- essentially, renunciations of U.S. corporate citizenship, in which an American company buys a business in a foreign land with low tax rates and then moves its headquarters there. President Barack Obama and some lawmakers in Congress are considering steps to end the practice. But it took the threat of a consumer boycott to make Walgreen take notice and keep its headquarters in Deerfield, Illinois.

During a conference call with analysts and investors Wednesday, Walgreen CEO Greg Wasson said a move to Switzerland was "not the right course of action," as it would have led to "potential consumer backlash and political ramifications."

Walgreen's decision probably does not mark the beginning of a new inversion-free era, but it's certainly a sign that political opposition to the practice has grown fierce.

"This is a shot across the bow of any U.S. corporation that is considering leaving the United States," said Roger Hickey, co-director of Campaign for America's Future, a progressive nonprofit that collected more than 300,000 signatures on a petition demanding that Walgreen not "desert America."

A chart from the report by Americans for Tax Fairness and Change to Win offers perspective on how Walgreen's tax dollars can be used.

Inversions have grown more common in recent years, particularly in the health care industry, as businesses try to avoid paying taxes in the U.S., where the top corporate tax rate is 35 percent -- although in practice, most companies pay nowhere close to that.

Last month, U.S. drug maker AbbVie bought its British competitor Shire in a $54 billion deal and now plans to move to the United Kingdom, where the corporate tax rate fell to 21 percent in April. Pittsburgh-based Mylan Pharmaceuticals, a maker of generic drugs, bought $5.3 billion worth of overseas operations from Abbott Laboratories in July, allowing it -- after a failed attempt to move to Sweden -- to pledge allegiance to the Netherlands, where corporate profits are taxed at up to 25 percent. Pfizer, another pharmaceutical giant, tried to invert this spring by buying AstraZeneca in a failed hostile takeover.

Most of those companies, however, aren't household names to the average American. Walgreen is different.

"Walgreens, that's a real retail company -- that's the kind of company that everybody knows," Brian McQuinn, an associate law professor at Boston College, told The Huffington Post. "It's a very high-profile target for political attacks."

Walgreen took a month of public drubbing while it mulled a move to Switzerland. Calls for a national boycott proliferated.

Politicians applied pressure, too. Former Labor Secretary Robert Reich recommended freezing the company out of political lobbying circles. Sen. Dick Durbin, an Illinois Democrat, wrote a public letter to Wasson, mocking the chain's slogan with the question: "Is 'the corner of happy and healthy' somewhere in the Swiss Alps?"

In May, Senate Democrats introduced the Stop Corporate Inversions Act of 2014, which recommends, among other things, forcing a large portion of a merged company's management and workforce to relocate to the new overseas location if the company wants to dodge U.S. taxes.

The bill "allows corporations to renounce their corporate citizenship only if they truly give up control of their company to a foreign corporation and truly move their operations overseas," Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who backed the bill, said last month.

Obama has signaled support for the bill. And Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew told The New York Times on Tuesday that the administration is "looking at a very long list of possible ways to address the issue" of corporate inversions.

Shareholders who stood to benefit financially from Walgreen's inversion are no doubt disappointed by the company's decision to stay put. But Walgreen might enjoy some positive publicity for a change.

"If the media goes out and says, 'Look at Walgreens, they're not moving, look how patriotic they are,'" Steven Halper, senior vice president at FBR Capital Markets, told HuffPost, "there could be more people saying, 'Hey, I like Walgreens, I'm going to shop there.'"

But even if this is a win for critics of corporate inversions, the trend is unlikely to stop unless the U.S. lowers its corporate tax rate to compete with smaller countries, Halper said.

"Over the long run, the capital will move away from the United States regardless of the stopgap measures," Halper said.

And the public may lose interest in the mechanics of corporate tax law long before Congress reconvenes to vote on a bill to close the loophole.

"Congress is in recess, and therefore there's no visible movement on any legislative front," Edward Kleinbard, a professor at the Gould School of Law at the University of Southern California, told HuffPost. "There is a moral failing here -- but the moral failing is the Congress of the United States failing to do right by its citizens by addressing what are obviously flaws in the [tax] statute."