"The secret of a great success for which you are at a loss to account is a crime that has never been discovered, because it was properly executed." Balzac, Le Père Goriot

Conversely, when execution is faulty and failure occurs, crimes are exposed, and an effort to apportion blame and punishment is launched by the guilty and innocent alike. This is an apt description of what happened when Bernard Madoff's investment firm collapsed. As long as high returns were being generated, no one wanted to ask questions, including the obvious "isn't this too good to be true?" When the music stopped and markets tanked, the entire scheme collapsed. Make no mistake: if his investments had continued to do well, Madoff would be in business today. But they didn't and he is now in jail, and at least four suicides, including his own son's, have been attributed to his crimes. Mr Madoff doesn't seem sorry for the risks he took, but certainly, he is suffering. Partial restitution has been made to his victims. There are certainly those who feel that although the regulators failed to prevent, the justice system was able to punish. The same applies in the Enron case.

This contrasts with the frequent refrain--why haven't more bankers gone to jail as a result of the global financial crisis? This has become a key demand of the Occupy Wall Street movement. The CBS news program 60 Minutes recently had a widely viewed and quoted segment that tried to answer this question, targeting Countrywide in particular. Many explanations have been offered, depending on your location within the political spectrum: the cause of judicial inaction is corruption, undue influence, the ability of the wealthy to hire the best attorneys, or simply that it is hard to convict people for making bad investment decisions in a free market environment.

This contrasts with the frequent refrain--why haven't more bankers gone to jail as a result of the global financial crisis? This has become a key demand of the Occupy Wall Street movement. The CBS news program 60 Minutes recently had a widely viewed and quoted segment that tried to answer this question, targeting Countrywide in particular. Many explanations have been offered, depending on your location within the political spectrum: the cause of judicial inaction is corruption, undue influence, the ability of the wealthy to hire the best attorneys, or simply that it is hard to convict people for making bad investment decisions in a free market environment.

Those who are most indignant point to the widely quoted number that more than 1,000 bankers were imprisoned as a result of the Savings & Loan Crisis of the 1980′s. The true number was 582, as reported by UPI in back in 1992, but that was still high in terms of the relative economic effect at the time:

The Justice Department said Monday it has charged more than 1,100 people so far in nearly four years of prosecuting the multibillion-dollar savings and loan scandal, winning 905 convictions but less than half a billion dollars in restitution. The department, in a release containing statistical information about the major savings and loan prosecutions, said 905 of 1,188 people charged in the scandal had been convicted in cases between Oct. 1, 1988, and June 30, 1992. Only 71 defendants were acquitted. The cases prosecuted represented $8.3 billion in losses to the thrifts. Of the 750 cases in which sentences have been handed down, judges imposed $11.2 million in fines and ordered $439 million in restitution. They ordered prison terms for 582 defendants but let off 168 without jail time. Among those charged, 137 were chief executive officers, board chairmen or presidents of savings and loan institutions. Of the high-level executives charged, 102 were convicted and 10 were acquitted.

Only $8.3B in losses--that certainly seems small beer by today's standards. Based upon 582 convictions, this represents a ratio of one jail term per $14.3M in losses. In his article in Foreign Affairs, Roger Altman estimated US losses as a result of the financial crisis to be $8.3 trillion. So add three zeros, and the number of people going to jail now at this loss-to-conviction ratio would be 582,000. Literally, half a million people! One-third by the way, would be high-level executives. California prisons are currently so full that they are turning out convicted criminals--where would we put all these people, and what would it cost to incarcerate them? To say nothing of the fact that we don't have enough prosecutors. The FBI has also decreased, not increased their manpower dedicated to white-collar crime since 2001, as priorities shifted to counterterrorism after 9/11.

The truth is that historically economic crimes, however they are defined, are not usually punished that severely even if they are uncovered; the S&L crisis was an anomaly. Not many of the tulip speculators ended up in jail, mostly it was the poorer blokes at the end of the chain who were thrown into debtors' prison. Another view: Economic crimes beyond stealing physical property aren't easy to discover, expose, define and differentiate from the normal market activity of selling something for more than it was bought. As Gary Becker, the University of Chicago economist explains his theory, "I was not sympathetic to the assumption that criminals had radically different motivations from everyone else."

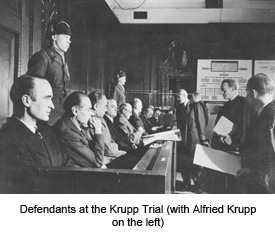

This ambivalence is true even in dealings between states under conditions of war and economic dictatorship. At the Nuremberg trials after the end of World War II, the industrialists who served the Third Reich by building gas chambers and weapons got off lightly compared with the likes of Adolph Eichmann. Alfried Krupp for example, one of a small group of businessmen who went on trial, was given the most severe punishment, and he went to prison for just 12 years. Krupp's firm lives on of course, as do the Japanese companies that built the weaponry of the Pacific--Mitsubishi is a name that has survived and thrived. One interpretation is that under the circumstances of war, or in times of financial distress, it is not possible or advisable to dismantle the infrastructure that holds a country together. This was certainly a tenet of US post-war reconstruction policy.

This ambivalence is true even in dealings between states under conditions of war and economic dictatorship. At the Nuremberg trials after the end of World War II, the industrialists who served the Third Reich by building gas chambers and weapons got off lightly compared with the likes of Adolph Eichmann. Alfried Krupp for example, one of a small group of businessmen who went on trial, was given the most severe punishment, and he went to prison for just 12 years. Krupp's firm lives on of course, as do the Japanese companies that built the weaponry of the Pacific--Mitsubishi is a name that has survived and thrived. One interpretation is that under the circumstances of war, or in times of financial distress, it is not possible or advisable to dismantle the infrastructure that holds a country together. This was certainly a tenet of US post-war reconstruction policy.

A popular view is that the lack of prosecution is the result of a lack of regulation, and there are now calls for new banking and financial industry legislation. However, this might just be the worst prescription possible. The real problem was lack of care in the enforcement process, as well as poorly written laws, according to Carole Basri, a legal ethicist and contributor to What's Next? She makes this point in her chapter 'The Future of Corporate Compliance':

The future of compliance lies in the shadow of the global financial crisis of 2008. Predictably, demands for greater regulation immediately followed the crisis. However, we do not need more regulations that will create more administration and more extensive compliance programs. We need better-targeted regulations that are consistently enforced, that foster corporate integrity, and that streamline the compliance process. Reductions in the number of compliance officers and of the funding of compliance programs will be counterproductive, yet this is precisely what is happening today.

Ms Basri's view is that ethics must be part of the 'compliance cocktail' and that ethics can be promulgated at an institutional level. All of this will require a more global outlook in order to be effective in the vast new marketplace for financial services in particular. This presupposes that people are motivated not just by greed, but also by doing the right thing professionally and as human beings, if given a chance. Which all harks back to the work of Adam Smith, especially The Theory of Moral Sentiments and the importance of values-based governance.

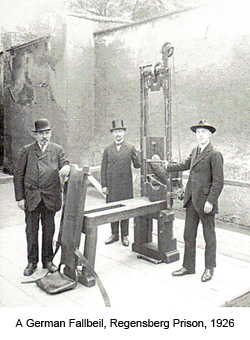

Another way of looking at this problem is from a revolutionary point of view. Financial crises can be seen as either the cause or the effect of political unrest, leading to what can be dispassionately described as a redistribution of wealth. The French Revolution was seen as a time of swift judgment against the wealthy, but in fact, economic crimes were not a focus at all:

The ultimate weapon in the war against the rich was, of course, the scaffold. In a period at which economic mechanisms were so unregulated that a large part of the population depended for their survival upon the black market, it was no longer possible to put a number to those guilty of a breach of the laws in force. Therefore sentences for economic crimes were relatively scarce. To be more precise, recent studies suggest that the Revolutionary Tribunal had pronounced 267 sentences of this sort, 181 of which were for hoarding or for failure to respect the maximum, and eighty-six for passing counterfeit money or for trading in assignats." -The French Revolution, An Economic Interpretation by Florin Aftalion

Disclosure is another critical issue that prevents a judgment of fraud. Many of the banks fully disclosed risks in the endless paperwork that accompanied both mortgages and mortgage-backed securities sales. The problem was that all of this was so difficult to understand that even Alan Greenspan, a math whiz, did not understand the risks. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that the Justice Department has concluded that criminal convictions might be difficult to obtain, and therefore it is doing the next best thing, which is offloading these cases to the regulatory authorities for possible civil penalties. Again, the upshot is no jail time. Indeed, cases against Countrywide, AIG, Citibank, Washington Mutual, and Goldman Sachs have gone nowhere. Loren Steffy, business commentator for the Houston Chronicle, also addresses this question:

Three years ago, I asked Sam Buell, the former federal prosecutor in the government's effort to indict Enron's Jeff Skilling, the question of whether we'd see widespread prosecutions from the financial crisis. His prediction: Don't count on it. As I wrote at the time:

In the current crisis, few people understood the complex debt instruments that had become common on Wall Street and therefore the firms failed to make good risk assessments. But what they were doing -- such as packaging dodgy mortgages into investment pools that were supposed to minimize risk -- was widely known.

"It's not a conspiracy if everybody's in on it," Buell said. "In order to have a fraud conspiracy you've got to have some effort by one group to deceived another group."

But what about the fact that America as whole seems deceived by what happened? Doesn't matter, Buell argues. Just because Main Street didn't understand what was happening doesn't make it a fraud. Those who are stand-ins for investor interest -- regulators, brokers, credit agencies -- "seem to have known what was going on," he said.

So the reasons that there aren't any trophy heads are plentiful: there are legal obstacles, practical obstacles, a lack of personnel, and general fuzziness about how economic crimes are defined. Convictions were high as a result of the S&L crisis, but it can be argued that few lessons were learned and a new banking crisis was not prevented as a result of vigorous prosecution. Still, it is early days, and political pressures are mounting. Surely prosecutors somewhere are carefully preparing their cases against high-profile bankers, just as legislators are drafting new regulations. Will any of this help the current situation or prevent another crisis? Most likely, no. But sometimes hungry crowds demand that heads must roll.

This post originally appeared at the Yale Books blog.

This post originally appeared at the Yale Books blog.

What's Next? Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy by David Hale and Lyric Hale is available now from Yale University Press.