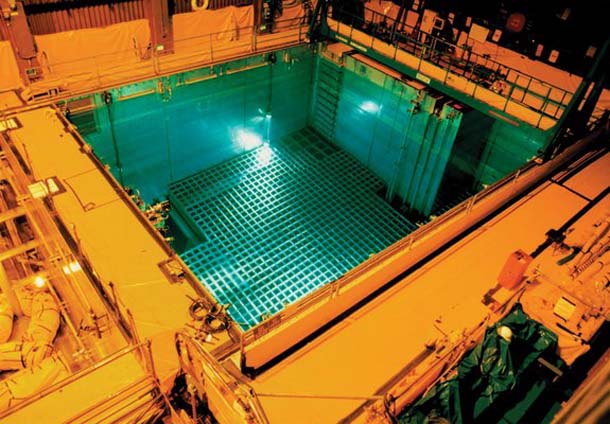

Some spent fuel pools hold five times the amount they were originally designed to accommodate. (NRC)

Haste makes waste--unless you're talking about nuclear power.

In that case, delay makes waste--tens of thousands of tons of it.

The waste--used, or spent, fuel--is dangerously radioactive and has to be sequestered from the environment for tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of years. And even though nuclear power is more than 50 years old, no one has figured out just where to put it. Right now that waste is piling up at nuclear power plants across the country, and most of it is sitting in congested, relatively unprotected cooling pools.

This problem received some media attention earlier this year when President Obama's Blue Ribbon Commission on America's Nuclear Future issued a report recommending what to do with the waste. One of the blue ribbon commission participants, geologist Allison Macfarlane, was approved by a Senate committee yesterday to become the new chair of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

The blue ribbon commission recommended building one or more interim storage facilities and reopening the search for a suitable permanent geologic repository site, given the Obama administration nixed plans to finish building one in Nevada. But the commission didn't offer any recommendations to strengthen on-site spent fuel management, and Congress hasn't addressed it, either--although there are signs that some lawmakers are beginning to snap to attention.

Trouble with a capital T that rhymes with P and stands for pool. Spent fuel consists of fuel rods that, after four to six years in a reactor, no longer produce energy efficiently. They still emit high levels of radiation and heat, however, so they have to be placed immediately in deep water pools to cool them. Initially the plan was for plant owners to cool spent fuel in pools for a relatively short period of time, and then ship it off to be reprocessed for reuse. But during the Carter administration, the government abandoned this ill-advised idea because it would have been more expensive than using fresh uranium, it wouldn't significantly reduce the amount of waste, and the reprocessed material could be used in bombs.

"When the plants were originally designed, plant owners thought that the spent fuel would remain on site only two or three months," said Dave Lochbaum, director of the Nuclear Safety Project at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). "When those plans changed, plant owners just filled the pools up to capacity without ever rethinking whether they should provide more safety and better barriers."

Some pools now hold as much as five times the amount they were originally designed to accommodate, according to UCS. That's not good. If a malfunction, natural disaster or terrorist attack triggered a leak or shut down the pool's cooling system, the rods would heat the remaining water in the pool, eventually boiling it off. If plant workers couldn't replace that leaking or evaporating water, the pool's water level would drop, exposing the fuel rods. And once those fuel rods are exposed to the air, the heat could damage their zirconium cladding, enabling radioactive gases to escape into the environment.

Spent fuel pools are located outside the primary reactor containment building and, according to Lochbaum, "are often housed in buildings with sheet metal siding like that in a Sears storage shed." In other words, spent fuel pools are a lot more vulnerable to a natural disaster or a terrorist attack than a reactor core.

Continuing to add spent fuel to the pools compounds the risk by increasing the amount of radioactive material that could be released into the environment. A large radioactive release from a spent fuel pool could result in thousands of cancer deaths and hundreds of billions of dollars in decontamination costs and economic damage, according to 2004 study in Science and Global Security, a journal published by Princeton University.

Everybody out of the pool. Even under the best-case scenario, a national interim storage facility -- let alone a permanent repository -- is decades away. And even if a disposal repository opened today, it still would take more than 30 years to ship the spent fuel from nuclear plant sites, according to a 2008 Department of Energy (DOE) estimate. That means that large quantities of spent fuel will continue to build up at reactor sites for many years to come. Today, approximately 74,000 tons of spent fuel is stored in 77 locations in 35 states. Of that, more than 54,000 tons -- 73 percent -- is sitting in wet pools, according to a May Congressional Research Service report.

Fortunately there is a way to reduce the safety and security risks associated with spent fuel pools: transfer the spent fuel to dry casks after it has cooled sufficiently, which generally takes five years. That was the conclusion of a 2006 report by the National Academy of Sciences, which determined that "[d]ry cask storage has inherent security advantages over spent fuel pool storage...."

UCS maintains that the waste can sit safely on site in dry casks for at least 50 years. A 2010 report by the nuclear industry's trade association, the Nuclear Energy Institute, was even more confident, stating that "existing dry cask storage technology, coupled with aging management programs already in place, is sufficient to sustain dry cask storage for at least 100 years at reactors and central interim storage."

In any case, plant owners eventually will have to transfer spent fuel to dry casks to ship it via rail or truck to an interim or permanent repository, so it makes the most sense to accelerate the transfer to the less vulnerable dry casks. Some plant owners have transferred some waste when their pools became too packed to add any more rods. Even so, only 25 percent of the spent fuel in the United States is now in dry casks, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Suing the DOE for damages. Plant owners aren't in a hurry to transfer spent fuel to casks for two reasons. First: the cost. According to a 2003 study by expected-to-be NRC chair Allison Macfarlane, UCS Senior Scientist Edwin Lyman and other nuclear experts, it would cost $3.5 billion to $7 billion to transfer all the spent fuel that has been in pools for more than five years to dry casks. Second: The NRC has not required plant owners to transfer the spent fuel because it maintains pool safety risks are not serious enough to warrant the expense. The agency points to the fact that, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, it required plant owners to disperse hotter fuel throughout the cooling pools to reduce the potential for a fire. But according to a blog Lyman posted earlier this week, declassified NRC documents cast doubt on whether this measure actually fixed the problem.

Meanwhile, approximately $26.7 billion is sitting in a nuclear waste fund established in 1982 by the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, which set an apparently unrealistic timetable for constructing a permanent underground geologic repository by the mid-1990s. That law required plant owners to make annual payments--now pegged at $750 million--into the fund to cover the cost of a permanent repository. That money can't be used to pay for transferring spent fuel to dry casks. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) introduced a bill in 2007 to amend the law so the fund could be used for interim waste storage. It died in committee.

Plant owners have filed dozens of lawsuits against the DOE, charging that the agency breached its contracts to accept spent fuel by 1998. Since 2000, the DOE has paid out approximately $1 billion in damage claims to cover costs incurred by plant owners "to construct dry storage facilities or additional wet storage racks, ... purchase and load casks and canisters, and [pay] utility personnel necessary to design, license and maintain these storage facilities," according to the Congressional Research Service.

Congress needs to act. Unfortunately there are no cheap or easy answers. Despite the Nuclear Waste Policy Act's restrictions, the courts are forcing the DOE to subsidize plant owners to transfer spent fuel, and the agency estimates that new lawsuits and other costs could eventually amount to a $16-billion legal liability. To stem those suits, Congress could pass a bill like Sen. Reid's. But that would raid the Nuclear Waste Fund to pay for spent fuel transfer, and drain the reserves needed to construct a permanent repository.

Congress needs to do something, and its primary consideration should be public safety. There is currently a bipartisan effort in the Senate led by Jeff Bingaman (D-N.M.), Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) to incorporate the blue ribbon commission's findings into a bill. That's heartening, but any bill they draft must go beyond the commission's recommendations to include language requiring plant owners to expedite the transfer of spent fuel to dry casks. If they fail on that score, the 120 million Americans who live within 50 miles of a nuclear reactor will remain at risk.

Elliott Negin is the director of news and commentary at the Union of Concerned Scientists.