Helen Keller's birthday was earlier this week. Icon of perseverance, symbol of hope, heroine of my girlhood. For years, I finger-spelled with classmates, later learning rudimentary American Sign Language because I was intrigued by the idea words could be made with fingers, bodies and faces as well as with letters.

I've read several biographies of Helen Keller. The idea that she born fine and then she wasn't horrified me. That Annie Sullivan arrived and used her fingers to teach Helen how to communicate fascinated me; the family's inability to help her, their well-meaning thwarting of Annie's techniques made sense to me, a career school teacher, the leader of a school. The Kellers indulged their daughter because they did not know better. It was Annie who saw what Helen needed and offered structure, discipline, and ultimately, language. Teachers sometimes see in our pupils what parents cannot. Helen Keller went on to be a formidable scholar. Her resilience continues to inspire me.

My fascination with the moment Helen understood language stretches back long before I could finger spell or had watched the Patty Duke-Anne Bancroft film. From the wings of a theatre in a former Chataqua auditorium in the summer resort of Eagles Mere, I inhabited Helen's story. In 1967, I was six. The Eagles Mere Playhouse produced The Miracle Worker, and I played the role of the smallest blind girl in the Perkins School for the Blind, hoping Annie would not leave me.

"Don't go, Annie, where the sun is hot," I said, loud and confident. And, "Don't go, Annie, away."

I was not the youngest of the little blind girls. Ginny was younger than I, but she was taller with red hair. When I fussed to Cherie, the actress who played Annie Sullivan and whom I worshipped, she consoled me, "You say your lines well; that's why the director gave you more of them. It doesn't matter that you're not really the youngest. You're acting." I was soothed. My love affair with theatre began.

The sound of Jimmy in the poor house calling out for his big sister, Annie, sent chills rippling through my scratchy dull shift, as I peeked from the wings. When I heard the lullaby that Helen's mother sang, "I gave my love a cherry that has no stone," I imagined I was Helen. I loved Annie. I'm not sure I made much of a distinction between Annie and Cherie, the actress. I know that I believed I was a blind child, hoping my favorite wouldn't leave me. I remember being off stage, transfixed by what I could see unfolding on stage. I had gone to the theatre before, certainly, watching the matinees for children, but this was a real play and I had a part in it. Ecstasy.

As a drama teacher and as a mother, that amazing summer floats back to me. Now, I watch young actors I have trained taking risks, soaring. For years, I crooned to my own fretful children, "The story that I love you, it has no end; a baby when she's sleepin' has no crying." That particular summer theatre experience marked me, sent me down the path that would become my life -- all because the theatre company needed a few local children to play the blind girls.

One afternoon, waiting outside for our cue on a damp mossy staircase, I lost my footing and tumbled all the way down the wooden flight in my grown-up flats. When I came to, I was lying on the grass outside of the Playhouse, Dr. Brackbill looming above me. I heard Ginny saying MY lines, and I struggled to get up. The good doctor gently pressed me down again, insisting on rest. I lay in Grannie's high bed, gazing out the window at the lake, jealous of Ginny worried I might be replaced. I wonder how my mother felt, if she worried because I did not come around quickly? We were decades away from the concussion protocol schools now take so seriously. The next day, recovered, I was back in the theatre, no worse for my fall, leaning against Annie's knee, wishing she would keep her cool hand against my cheek a little longer.

A few years ago, I "friended" Cherie, my Annie, on Facebook and thanked her for the care she had shown me, for kindling my love of theatre, my commitment to teaching.

In college, I auditioned for the play again, hoping, hoping to be Annie. Instead, I am Aunt Ev, ineffectual, dithering. Still, it was a Dramat show, so though the part was not much, I was still excited to be a part of the production. Kay was our director, and she was a teacher, guiding us to become a strong ensemble. I admired Becky, who played Annie, and I loved Nancy, who played Helen's mother. I was old enough now to have spent lots of time in the theatre, aware how a production came together, but it still felt as magical as it did when I was six. And, it was during that production that I met Seth, the man I would marry though, of course, I don't know that then. One December day, I left rehearsal early, not feeling well, and when I returned, Seth was alone in the theatre. The time of the call had been changed, but no one had told me.

"Well, as long as you're here, would you mind sitting on stage, so I can focus the lights?" he asked, skinny in jeans and a t-shirt despite the cold theatre.

Mind? Of course not. He was cute. I moved from one spot to the other on the set as he climbed up to refocus fresnels and lekos. Did we talk? I can't remember. I do remember the feeling of being there with him, the glow of the lights. We didn't get to know each other well during that production, though I learned he had a serious girlfriend back in Ann Arbor. He was the lighting designer; I, a lowly freshman. But over the next few years, we grew to be good friends and later, much later, we fell in love and started a theatre program of our own.

The Ensemble Theatre Community School was the six-week summer theatre program Seth and I and our friend, Eleanor, founded and ran for almost 30 years in Eagles Mere. Our stage was in the DeWire Center, the Playhouse having fallen down one winter, the weight of the snow too much for the elderly wood. But our little company of student actors lived in the same house that actors from the Playhouse had lived in each summer for decades, The Players' Lodge, in between The Sweet Shop and the Presbyterian Church. Alvina Krause, the Playhouse's artistic director, was long dead, but I conjured her as we made plays. I hoped she would be proud we had brought theatre back to her mountaintop.

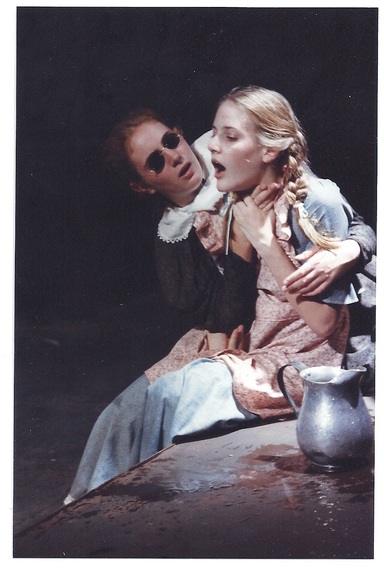

In 1994, we produced The Miracle Worker. Our daughter was small and I was pregnant with another baby -- our own miracles -- so Peter directed the play with a concept that each character had a doppleganger. Kyra played Annie. She was tall, coltish, strong and young; she struggled to learn her lines, but her determination mirrored Annie's own. Barbie played Helen, daring, feral, brave in her trust of the others in the cast, rehearsing with a blindfold and earplugs. I watched, again from the sidelines, as an Artistic Director does, seeing the play take shape, suggesting "I gave my love a cherry" as a lullaby, transported back to my own first moments in the theatre.

Decades after that first Miracle Worker, I, myself, was an acting teacher, helping kids learn to be authentic on stage, to eschew overacting, to allow themselves to be vulnerable. For some, I hope I served as a metaphorical Annie, unwilling to give up on connection, no matter how defended and fierce a young person might seem.

In that production in Eagles Mere in the 90's, Seth figured out how to make the pump actually pump water. On opening night, I shooed away my disdain of cliché and cried a little bit as Kyra pumped water into Barbie's hand and spelled, W-A-T-E-R. Triumph. Connection.

There are moments that shape us. Helen Keller's story; Annie Sullivan's story -- these are stories that have taken root inside of me, cliché or no cliché. I am awed, grateful to William Gibson for writing this script, lucky to have spent portions of my life in close proximity to wonder and revelation and struggle and awe.

I am a teacher because I stood in the wings of a theatre when I was six and fell in love with a story... and with a girl and her teacher and what they accomplished. Happy birthday, Helen. Thank you, Annie.