With the release of such cultural touchstones as Michael Pollan's The Omnivore's Dilemma and Robert Kenner's Food, Inc., the late-aughts of this century saw interest in food systems make the leap from middle-America ag-extension stations to parental gossip sessions in playgrounds from coast to coast. A keyword search for "sustainable agriculture" on the New York Times' website yields 1,366 results since 2000, covering subtopics that range from locavorism to cover-cropping to Walmart's sourcing practices. In this unlikely intersection of agricultural science and popular culture, certain questions seem to dominate the discussion: Pesticides or no pesticides? Local or organic? USDA-certified or farmer's word? Natural or hormone-free or cage-free or free-range?

This is a consumer-oriented discussion, designed to answer the (not-uncomplicated) question of, "What should I buy?" And although media coverage of grower-oriented sustainability metrics does exist, there's one factor that's been largely missing from this chemicals-are-killing-our-planet vs. chemicals-are-feeding-the-world broken record of a debate. It's a factor so big and so obvious that its omission feels like a symptom of some weird post-industrial amnesia. That factor is the weather.

When you work in an office, the weather is the difference between a 30-minute and a 45-minute commute. But when you work on a farm, the weather is the difference between a decent harvest and a terrible one. Between paying your mortgage and foreclosure. Between making a living and--not. So it's no wonder that while metropolitan farmers market clientele talk themselves blue over the value (or lack therein) of a carbon footprint label, when you ask farmers what they need to know more about in order to improve their operations, they say the weather.

Energy company Schneider Electric has been providing services to farmers for over 20 years through its agricultural brand, DTN/The Progressive Farmer. When they introduced weather forecasting as part of their platform, it quickly became one of their most popular services.

Up until this time, farmers relied on regional weather forecasts from airport weather stations that were updated once or twice a day. So in order to provide farmers with a more accurate and specific forecast, Schneider created the WeatherSentry program, which relies on sensors the company installs in farmers' fields.

According to Ron Sznaider, Vice President of Schneider Electric's weather division, WeatherSentry now has more than 4000 subscribers. With an average farm size of 1500 acres, that's six million acres that are now managed with an eye to the particular microclimate--not just of each farm--but of each field where a WeatherSentry Weather Station is installed. And because the WeatherSentry platform pulls data hourly from those sensors, subscribers can now make operational decisions that reflect what are often rapidly changing conditions.

"Rainfall in particular can vary so much over relatively short distances," Sznaider says, so a farmer relying on the regional airport forecast might decide to fertilize his fields in the morning, only to see it all washed away in the afternoon by a storm that those sensors didn't pick up on: money down the drain.

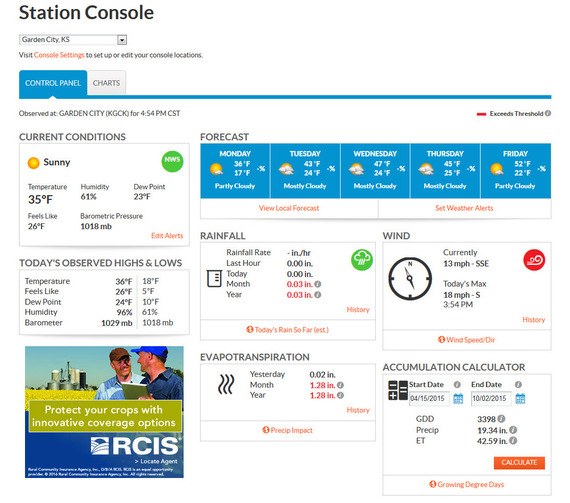

For a one-time installation fee of $500 and an ongoing service fee of $50 a month, WeatherSentry subscribers gain access to an online platform that pulls the data from their field sensors onto the internet. The website features weather forecasts, rainfall over time, wind conditions, temperatures, and evapotranspiration rates specific to the farmer's land; historical weather data is also provided, as well as regional trends, to provide temporal and spatial context. This information allows subscribers to use their time more wisely and save money on inputs by reducing waste, Sznaider says. But this isn't just about farming's economic viability--it's a matter of environmental sustainability as well, with the potential to mitigate agriculturally-associated ecological damages over millions of acres in this country's heartland.

In order to understand how that might be, we need to take a quick look at the nitrogen cycle. Farms like those that subscribe to the WeatherSentry program tend to amend the soil of their corn and soy fields with synthetic nitrogen-based fertilizers. Once the nitrogen is on the fields, it can either be taken up by the plants and used for growth or lost through leaching and denitrification. This loss is where environmental damage happens: contaminated drinking water and eutrophication from leaching; increased atmospheric nitrous oxide (a greenhouse gas that is 300 times more potent per pound than carbon dioxide) from denitrification.

Two factors that have a big impact on how much nitrogen is lost from a given fertilizer application are temperature and rainfall. Without a highly localized, highly accurate weather forecast, it can be very difficult to predict how these factors will play out, so farmers tend to apply more nitrogen than would be strictly necessary under ideal conditions in order to make sure that at least some of it gets to their plants. But if farmers had access to precise weather data, they would be able to schedule their fertilizer applications for times when there would be minimal loss. Less uncertainty, less fertilizer in the fields, less nitrogen in the ecosystem.

Whether you're a corn farmer trying to save money on inputs or an organic proponent advocating for reduced agricultural chemicals, pretty much everybody agrees that less nitrogen fertilizer would be better--except, perhaps, the fertilizer companies. But as agricultural operations become increasingly vertically integrated, finding an agricultural company that still focuses on only one product - in this case, anhydrous ammonium fertilizer - is getting more and more rare. And if farmers are more interested in buying weather IT than they are in buying fertilizers--or tractors, or herbicides, or whatever else--then it's in the interest of agricultural companies to diversify their offerings and meet that demand with a supply.

This may have been part of the thinking behind agribusiness giant Monsanto's 2013 acquisition of the San Francisco-based weather information company Climate Corporation. Unlike WeatherSentry, Climate Corporation doesn't install hardware in farmer's fields, but rather pulls data from external sources in order to create a similar value proposition: field-level weather forecasting delivered to a frequently updated online platform designed to help farmers maximize efficiency of both time and inputs. And despite the reputational risk of fraternizing with the much-hated Monsanto, the nearly one-billion dollar deal has afforded Climate Corp the opportunity to scale its impact to an acreage the size of which dwarfs WeatherSentry's current reach by two orders of magnitude. Potentially, that's a lot of nitrogen fertilizer saved.

Mark Bomford, director of the Yale Sustainable Food Program, considers Monsanto's purchase of Climate Corp to be a telling barometer-reading for the future relevance of agricultural weather services--emphasis on services. "Precise weather data is good, but does very little on its own. It's the prescriptions that emerge from this information that are really important." He maintains a certain wariness regarding the inevitable intersection of corporate and agricultural interests. "Who's doing the prescribing? What are the prescriptions worth? Who owns them? That's likely where the value proposition is, as well as the locus of power." So how to avoid a collision of competing stakeholders: farmers versus shareholders?

One way is to eliminate shareholders from the picture by implementing open-source versions of weather sensing technologies and leaving it to farmers to maintain and interpret the data themselves. Bomford came to Yale by way of the University of British Columbia, where he worked with Davis Vantage Pro2 weather stations on the university's farm. But while he was impressed by the hardiness and accuracy of the sensors, the instruments were expensive and the associated software nonintuitive. "My experience with this makes me skeptical of claims for turnkey, user-maintained climate data."

Instead, Bomford says, "If I were to turn distributed climate data into some kind of social enterprise, I would offer open-source hardware so that those who want to maintain their own equipment could if they wanted to, but the core value proposition would be climate monitoring services with a prescription package that promises to reduce purchased material inputs, not increase them."

While Schneider Electric is making no such overt promises to WeatherSentry subscribers, it did recently commit to open the use of its weather data to the global research community. Speaking at COP21 in Paris this December, Schneider pledged to grant researchers access to what Ron Sznaider calls the company's "emerging rural climatological record" as part of the UN's Data for Climate Action campaign.

According to the company's data, "the weather is becoming more volatile and more dynamic," Sznaider explains. "Individual storm events are becoming more intense. High temperatures are higher, low temperatures are lower. Heat waves and cold arctic blasts are lasting longer." And it's not just what is changing, but how: "total rainfall amounts over a long period appear to be the same, however the rain is happening in shorter bursts," which causes more flooding. With it's accuracy and richness--both spatially and temporally--Schneider's WeatherSentry data offers a remarkable window into the evolving climate of the North American interior. Through research partnerships, its applications need not be limited to agriculture.

They also need not be limited to North America. In addition to promising to share data with researchers, Schneider announced plans to develop WeatherSentry platforms for use in developing nations. "Developing nations are frequently lacking in both availability of accurate weather information as well as capabilities to mitigate adverse effects," Sznaider says. How, exactly, the weather stations might need to be adapted to meet the needs of different farming and infrastructure conditions is still an open question. Ultimately, Sznaider hopes, this expansion could help support a safer and more productive food system throughout the world.

Whether it's at a field-by-field scale or international scale, the systems-level change proposed by weather information technology does seem stylistically out of step with the food movement's usual MO. These technologies aren't radical or romantic. They're incremental. They're patentable. They're geeky. And they come with some serious corporate baggage.

All of which might make some in the sustainable ag old guard nervous--and understandably. Agribusiness does not have a tremendous track record when it comes to ecological (or social) responsibility. But luckily, there is room in the food system for more than one kind of change to be taking place at the same time. In fact, simultaneous change along multiple pathways might be an imperative in the struggle to fix what's broken about current methods of global food production. Some strategies will peter out, and some will stall, and some will backfire. Hopefully, though, some will work.

Work for whom? is an important question to keep asking. There's nothing inherently oppressive about technological solutions to environmental questions, but the possibility for manipulation and co-optation is ever-present. Opening up data access to external researchers is a good step toward encouraging the use of agricultural weather platforms for positive outcomes at the community, not just the corporate, level. But to ensure that the innovations generated in the corporate sphere are used in a responsible manner requires constant engagement--not just from producers, but from consumers as well. Rather than demanding organic at all costs, we can become flexible enough in our buying habits to create a market for lower- (as opposed to zero-) input agriculture. And once we're willing to buy produce that occupies this middle ground, we can use our buying power to hold growers accountable for reducing their fertilizer applications.

As the disruptive force of climate change looms, we all have an interest in the insight that companies like Schneider Electric and Climate Corp have to offer. But whether or not that interest is respected is up to the mechanisms we put in place to govern its application and distribution. For better or for worse, knowledge is power.