Friends following the revolt on the Nile on their television screens in the U.S. are asking: "Are you leaving?" Planeloads of American expats, trapped tourists and other assorted foreigners are being evacuated. But the departures should not leave a false impression. Living conditions in Cairo and the risks to foreigners are not quite as bad as they may appear in the media. The streets could get ugly again but only if the Egyptian regime decides to use lethal force to snuff out the peaceful protests -- unfortunately, the violent, pro-regime gangs unleashed on protesters in Alexandria and Cairo Wednesday may be a sign of worse to come. As a longtime resident of Cairo, I have no hesitation whatsoever about staying put.

As the "million-man-march" was underway in downtown Cairo on Tuesday, I took a taxi with some Egyptian friends for a six-hour ride up and down the Nile and back. I traveled from the affluent southern suburb of Maadi where I live to the densely populated working class northern district of Shubra and home again. We were stopped at more than 50 checkpoints set up by citizens wielding sticks, knives and in some cases firearms. At each one we had to hand over our IDs, including my Navy blue American passport. Nobody complained about my nationality. A dozen times I was told, "Welcome to Egypt!"

"See?" my old friend Mohammed asked me. "Everything will be good in Egypt now." I certainly did not hear the words "Death to America," one of the famous sayings from the Iranian revolution in 1979. Despite the scaremongering of some American pundits, Egypt's uprising against an authoritarian ruler bears little similarity to the overthrow of the Shah 32 years ago next week. What I saw on the streets of Cairo--including a pop-in at the protests in Tahrir Square--was a population proudly taking ownership of their country, and displaying the hospitality to outsiders for which Egyptians are famous.

Our first checkpoint after leaving my apartment was at the end of the street. A dozen young men using a tree branch for a roadblock stopped our taxi. They were all armed with clubs. One of them brandished an axe. As would be the case at every checkpoint, they carefully scrutinized the IDs and inspected the car for weapons or explosives. Then they politely apologized for the inconvenience and waved us through. Riding around Maadi to inspect the local looting, which occurred in the wake of the initial protests, we went through another dozen similar checkpoints. It was quite remarkable: after Egyptian police abandoned their posts, ordinary people took over the nation's security.

Next we drove north along the riverfront corniche toward Tahrir Square. The usually gridlocked road was empty. We saw tanks and armored vehicles manned by the army at the entrance to Maadi, location of many diplomatic residences. In Old Cairo, site of churches and a synagogue dating back a thousand years, the police station had been attacked. In a scene we were to see in almost every neighborhood, there were burned out police vehicles on the roadside.

We crossed the Nile over to Giza where there were more tanks at a key intersection where a Sheraton Hotel stands near the residence of the late Anwar Sadat. To check out the Tahrir Square protests, we drove to the island of Zamalek and parked the taxi at the Cairo Opera House, where my daughter had violin lessons every Friday morning for 10 years. On the Kasr el-Nil bridge and in Tahrir, people were in a buoyant, confident mood. I have known the same atmosphere during the Beirut Spring in 2005 and in South Africa following the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990.

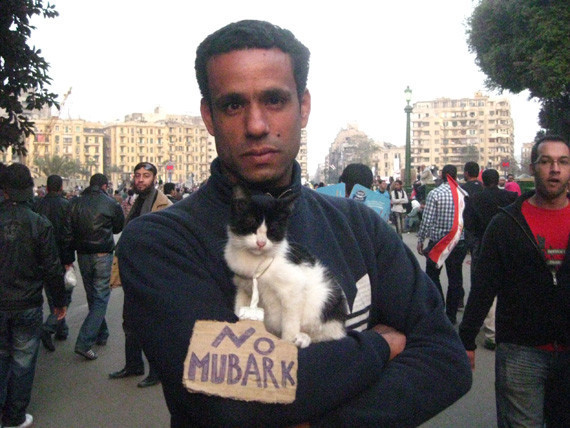

Many were there to just witness history. The hundreds of Egyptian flags--being waved or wrapped around bodies--reflected the nationalist sentiments. Scores of signs I saw read "Down, Down Mubarak," but I didn't see any placards against the U.S. or Israel. I asked a man if I could photograph him holding his cat, which had a little protest sign saying "No Mubark" around his neck. One of the protesters wore a t-shirt with "Lust for Life" written on it. "My generation was stupid," Mohammed reflected, as we left the demonstration. "We sat for 30 years with our mouths shut. My sons are smart. They have the Internet, and know what is happening in the world."

We tried to enter the upscale residential neighborhoods of Zamalek, where I had lived for a total of nine years. A band of armed residents were very aggressively keeping cars out, so we turned around and headed up the Nile again. We encountered numerous checkpoints where army personnel and local residents worked together to inspect vehicles and check papers. Finally, we arrived in Shubra, a massive garbage-strewn sector of the capital whose residents may be equal in number to half the population of Israel. Our car wound its way through crumbled streets partly flooded as usual by water main breaks. At one intersection after the other, we were stopped by tough-looking armed young men who seemed proud to be doing their part to protect Egypt. Surprised to see an American in this part of town, a few times different men told me, in English, "Don't be afraid, you're safe here." We drove by some of the numerous Christian churches in the area; they were untouched in the disturbances.

After night fell, the number of roadblocks increased. On the west bank of the Nile, we stopped at more than a dozen on the way south back to Maadi. At the last checkpoint before crossing the river to the east bank, men warned us not to take the new six-lane Ring Road bridge because bandits were ambushing vehicles there. So we turned around and crossed at another place. When we got to Maadi around 9 p.m., six hours after the start of the daily curfew, the army had completely sealed it off. As one Maadi resident flew into a rage about not being allowed to drive to his home, a local army commander shouted angrily and fired a half dozen shots in the air.

I said goodbye to the friends, got out of the taxi and walked the rest of the way home. A bit later, in my pajamas, I went down to the campfire on the street corner where the men of our neighborhood security detail were watching a TV with President Hosni Mubarak announcing that he would not run for another term of office. Mubarak was already president when I first came to Cairo 28 years ago. "Welcome to the new Egypt," I said to myself.

Scott MacLeod, Time's Middle East correspondent from 1995 to 2010, is managing editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs and a professor at the American University in Cairo.