For the past several months, the Obama administration has been considering a trade dispute with important implications for all 50 states. The massively subsidized, state-owned airlines of Emirates, Etihad, and Qatar Airways have taken unfair advantage of the Open Skies aviation agreements that the United States has signed with the governments of the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. These agreements permit the three Gulf airlines unlimited access to the entire U.S. - the largest airline market in the world. In exchange, U.S. airlines can fly to Qatar and the UAE from anywhere they want, as much as they want.

Contrary to the willfully misleading rhetoric advanced by the Gulf airlines and their supporters, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, and United Airlines strongly support the Open Skies agreements the United States has with more than 110 countries, which have benefited the airlines and their workers. The U.S. trio have formed joint ventures with European and Asian airlines to expand their networks, and these have been good for travelers and carriers alike - and for U.S. cities and states, all of whom welcome tourism, inward investment, and other economic advantages that air service confers. But Open Skies agreements are clear on a key point: to access the vast U.S. market without constraint, a foreign airline cannot be subsidized. Thus, it's time for our government to take action.

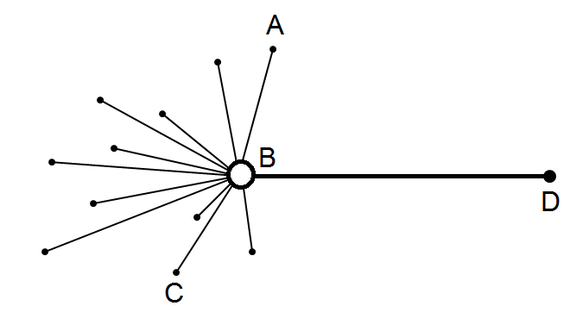

One of the less understood implications of the continuing, subsidy-fueled Gulf expansion is the threat to the U.S. domestic airline network. To understand how this works, you need to know how hubs work. Let's start with a little diagram. The picture below shows a greatly simplified hub-and-spoke network - using a single hub as an example. B is the airline hub, while A, D and C represent the spokes, or additional routes from the hub to other airports. Just as a bicycle wheel gets wobbly if spokes are broken or missing, in a hub-and-spoke network each spoke depends on the other for strength and viability. For example, there may not be enough demand for an airline to profitably operate a flight from A to B (a hub city in this case), but when the A-to-B flight "feeds" passengers onto flights from B to C and the other spokes, as well as onto the long overseas flight from B to D, the A to B flight becomes viable.

In the past two decades, U.S. airlines have been adding a lot of long-distance international services - like a Delta flight from Detroit to Amsterdam - made possible by the growth of tourism in both directions, the rise of multinational businesses, immigration, and other factors. The new Amsterdam services would not be possible without the passengers that connect through Detroit and from cities like Grand Rapids, Michigan; Kansas City, Missouri; Little Rock, Arkansas and dozens more. More than half of all passengers on a typical American, Delta, or United overseas flight make a connection to or from a domestic flight.

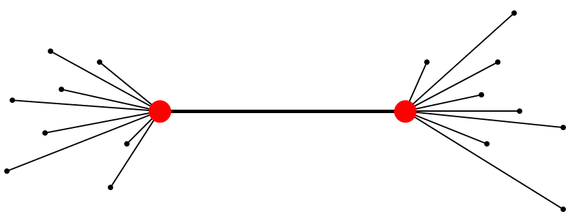

These long-distance (B to D) flights become even more viable with the growth of airline alliances like Star Alliance, SkyTeam, and oneworld, co-founded, respectively, by United, Delta, and American. These ventures are truly win-win: customers enjoy the benefits of a larger global network and, of course, perks like frequent-flyer points for connecting flights on the partner airline; and the airline is able to build a "virtual network" with its ally with much less capital and risk than if it were to fly its own planes. It's worth noting here that the Gulf carriers don't face these capital and risk constraints, because of the wheelbarrows of cash they can tap from their government owners.

With alliances, U.S. airline networks become even more robust, because now they are truly worldwide, and look more like this (but with many more spokes from multiple hubs):

While the benefits strong and robust networks is clear, global networks also present risks because the much larger network adds more interdependency, and is more vulnerable to external threats. And today, the biggest threat to the U.S. aviation networks comes from the state-owned Emirates Airline, Etihad Airways and Qatar Airways, none of which are subject to the expectations of real investors and lenders. So instead of prudent network expansion, the route planning strategies that the Gulf carriers becomes a question of where they strategically want to fly, rather than demand: "Airbus has just delivered another 500-seat A380; where should we fly it?" The Gulf trio claim that their expansion in the U.S. has not harmed American, Delta, and United, but the facts prove otherwise. Each new U.S. gateway that Emirates, Etihad, and Qatar Airways add reduces the viability of 1) U.S.-operated transatlantic flights; 2) the services U.S. airlines' joint venture partners operate beyond European hubs (like Frankfurt for Lufthansa, allied with United) to points in Africa, the Middle East, and all of Asia; and 3) crucially, the whole U.S. domestic network.

American and Delta have both withdrawn service to the huge U.S.-India market because they could not compete with the subsidized Gulf carriers. As U.S. airlines are forced to cancel long-distance international routes, domestic spokes lose traffic, and at some point a flight becomes unprofitable and gets canceled. That doesn't affect people who live in New York, Washington, or Los Angeles, but it should be a real concern to people in Birmingham, Alabama, Grand Junction, Colorado, and dozens of other small and mid-sized cities.

Civic leaders and economic-development experts know that loss of air service is not just a blow to local pride: it causes real economic pain. Airlines and airports generate enormous economic activity - it's been estimated that each U.S. daily widebody roundtrip lost or forgone because of subsidized Gulf carrier competition results in a net loss of over 800 U.S. jobs. Whether a long-haul international flight disappears or a domestic "feeder" flight is canceled, the job loss and reduction of economic activity is of three kinds: direct (a U.S. flight attendant is laid off); indirect (the U.S. airline buys less from local suppliers); and induced (the direct and indirect declines cycle through the economy - the flight attendant doesn't go out to eat, so the restaurant and its suppliers lose business). This is not pie in the sky - it's how the economy works.

One of the fibs that the Gulf airlines and their supporters keep repeating is that U.S. airlines are being "protectionist," which couldn't be further from the truth. American, Delta, and United don't need protection from competition. U.S. airlines are able to effectively compete with airlines from across the world when the playing field is level. In the case of the Gulf carriers, the U.S. needs to protect its aviation industry against unfair competition that distorts the market. By doing so, the Obama Administration will protect the rule of law and American jobs.