It is a truth universally acknowledged that being a mother who is a writer is difficult. Something I like to remind of myself as I, say, scroll HuffPost Parents for commiseration, is that it used to be much harder.

As an example, my maternal grandmother always wanted to be a writer. But how, in the era before microwaveable nuggets and iPads, was a mother of four to eke out time to write? She had a quirky wit and a penchant for the outrageous; she would have made an excellent mom-blogger, a superlative tweeter. But in the 1940s and '50s, there were no blogs or online lit journals. Writers published books, or stories in women's magazines. If you were a housewife in a Midwestern small town, you only dreamed of those things.

Still, she wrote. Her children remember her "banging away at an ancient portable typewriter and emitting blood-curdling whoops and hollers whenever she thought she had written something especially funny or blood-curdling." Even if no one was going to ever read it, she kept on banging away at that old typewriter her whole life long.

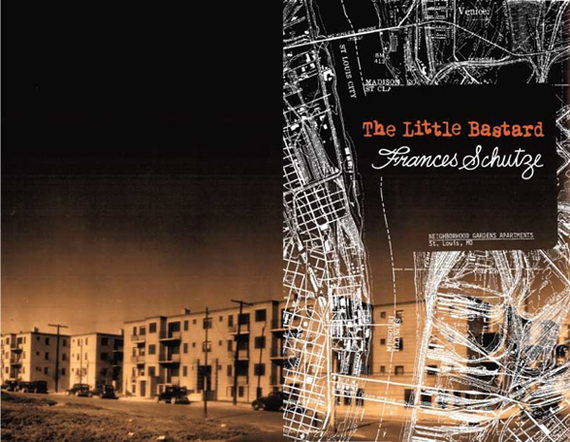

After my grandmother's death, my aunt found some suspiciously heavy black trash bags in her room at the nursing home. Sifting through them, she found sheaths of my grandmother's writing, dating back decades: letters, journal pages, a few radio plays, and a short story irreverently titled The Little Bastard. "How sad," she thought, and saved them.

The thing is, these bits of writing were good. I read The Little Bastard several times over the course of a few years before I realized that I could retype those illuminated onionskin pages, combine the working drafts together. And it took me a while after that to think of trying to share the story further. There are other stories in the pile, too, and a few radio plays and countless letters and journal entries. Even when no one cared, even when no one wanted to read them, even when it would have surely been easier to just stop, my grandmother wrote. And it all almost ended up in the trash.

When I asked my mother why her mother had never been able to publish her work, my mother hypothesized that "she didn't feel entitled to make it be a priority. She had all these other duties as a mother, minister's wife and teacher, and in her free time felt a responsibility to do Good Works for her community." In other words, there were a lot of duties to juggle. Of course, we all have lots of duties to juggle. I have a lot of duties to juggle; you have a lot of duties to juggle. As the writer Anne Morrow Lindbergh put it, "What a circus act we women perform every day of our lives."

What lesson can I, a writer and a mother, (can any of us, for that matter) glean from my grandmother's thwarted literary ambitions? I think the key lies in what my mother said her mother couldn't do: feel entitled to make it a priority. It's hard to say, I need to make the time to make this, even if that is inconvenient for everything else. My story is important and I need to make it. It goes against the grain of what we are supposed to do and be as wives and mothers. After all, what good is a short story to your family? If they're being honest with themselves, our families would probably prefer that our creative urges resulted in delicious pies. Writing a short story -- working hard on it, writing and rewriting, making countless marks and notes again and again -- all so it can sit in a drawer for 70 years? How dare one make that the priority? What good is that? When the kids are hungry, need help with their homework, want your attention now now now?

I know what good it is. If a writer doesn't write, she goes mad. So we write. And I'm willing to bet that many more mothers than we know have written (or painted, or played music) and had no one save their work from the Hefty bags of time. Seeing The Little Bastard make its way out into the world feels like a literary fist bump to all those women out there. Let's do this, mamas. As my grandmother wrote, "There's no limit to a woman's imagination."

The Little Bastard is now available from Anchor & Plume Press.

The Little Bastard is now available from Anchor & Plume Press.

Like Us On Facebook |

Like Us On Facebook |

Follow Us On Twitter |

Follow Us On Twitter |

![]() Contact HuffPost Parents

Contact HuffPost Parents

Also on HuffPost: