When you hear the words "Iraqi prime minister" and "third term" in the same sentence, you start to wonder. While Iraqi politicians gather in smoke-filled rooms in Baghdad to haggle over April's parliamentary elections and choose the next prime minister, 11 years after the removal of Saddam some are asking, is Iraq sliding into another dictatorship -- or all-out civil war -- under Nuri al-Maliki?

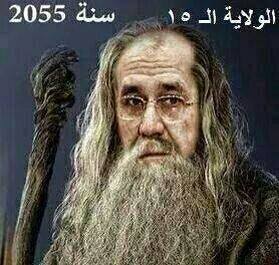

Maliki has served eight years as prime minister and doesn't appear to be in any hurry to leave. A picture doing the rounds among Iraqi Facebookers shows a rackety, grey-bearded Maliki in 2055, celebrating his 15th term as prime minister. As the leading Iranian stooge in the Middle East, he may be here to stay.

"A dictatorship can take many forms," says Samir Sumaidaie, a former Iraqi minister and ambassador in Washington. "It rarely appears suddenly from nowhere. In Iraq there are many of the warning signs that despite the trappings of democracy, the people will gradually be cowed, opposition smothered and a despotic regime based on a mafia-like, corrupt ruling class would emerge."

Sumaidaie says regime survival is Maliki's sole achievement. "As a politician who is bent on staying in power as long as possible and milking the state for all it's worth for the benefit of his family, cronies and mercenary Dawa Party followers, he is a success. But as a head of government responsible for building and preserving the institutions of the state and serving the people, he's a spectacular failure."

The charge sheet against Maliki is comprehensive. Critics say while he has been relentlessly concentrating power in his own hands and taking personal control of the security forces and intelligence services (straight out of the Saddam handbook), virtually all key indicators have gone backwards.

Public services, such as healthcare and education, are barely functioning. Infrastructure is crumbling. Sitting on a lake of oil, Iraq should be one of the richest places on earth yet it remains strangled by a command economy with a massive and dysfunctional public sector, a legacy of the Baath Party under Saddam. "Iraq is one of the last centrally planned economies on earth and this must change if they are to have any hope of creating the jobs they need," says Zaab Sethna of Northern Gulf Partners, which specializes in Iraqi investment.

As for security and the violence that continues to tear Iraq apart, Maliki, despite monopolizing the state's coercive powers, has been an abject failure. Last year was the deadliest for five years, with almost 9,000 killed in raging violence, an average of 25 a day. Astonishingly he has managed to lose control of swathes of western Iraq, which have slipped into Al Qaeda's hands. At least Saddam kept a lid on things -- and held Iran, the great winner of the 2003 war, at bay.

Maliki is an unlikely dictator. A charisma-free zone, he is no rabble-rousing Castro or Chavez. Yet behind the balding, bespectacled exterior lie a ruthlessness and steel that have many worried about Iraq's future direction. Those who cross him, such as Vice President Tariq al Hashimi, framed on terrorist charges and sentenced to death in absentia in 2012, are soon disposed of. Amnesty's latest annual report could be describing Saddam's Iraq: peaceful protesters shot dead, thousands of detentions, hundreds of death sentences after unfair trials, dozens of executions, torture and ill treatment "rife."

Should we be surprised? Probably not. As a rule, Iraqi leaders don't willingly step down from power -- or pay attention to human rights. In the 40s and 50s, Nuri Pasha served eight terms as prime minister. When he was killed during the 1958 revolution that brought the monarchy to a bloody end, Iraq entered a turbulent period, punctuated by coups and assassinations that only ended with the rise of Saddam to the presidency in 1979. He wasn't very keen to stand down, either.

Whatever Iraqis may tell you to the contrary, there's nothing new about sectarian division here. Although some blame Americans for unleashing it after 2003, the fact is Iraq has been at the fulcrum of the Sunni-Shia divide since the seventh century. When the Sunni Abbasid caliph Al Mansur, founder of Baghdad, died in 775, he left a crypt full of corpses. Every one of them was a Shia. Sectarian strife has been a regular feature of life ever since.

I've heard Sunni aristocrats talk about Shia politicians as "upstarts," "kebab-sellers" and "car-dealers" with a visceral loathing. With only a fleeting exception in the Middle Ages, Sunni minority rule over the Shia majority has been the norm. The loss of power to the Shia has been a cataclysm for Sunnis. Many refuse to accept it.

So sectarian tensions, ethnic rivalries, Iranian influence, Islamist extremism and terrorism all on the rise. National unity as elusive as ever. Corruption rampant. An unreformed command economy strangling development. Whoever becomes Iraq's next prime minister, don't expect things to get much better anytime soon. One of my old friends in Baghdad sounds bleaker than ever. "Iraqis have lost all hope in the future," he says.