My granddaughter is a homework burnout in second grade. Every day for the past almost two years, she dutifully takes those homework sheets out of her backpack and completes them. If she has dance class after school, she still completes them before bedtime. And what has she learned from doing this? Well, she asked if she could be my guest blogger this week, as she has developed a hatred of homework at the tender age of eight.

She doesn't actually hate all homework. On the rare occasions she is given a project to do, she dives in enthusiastically. Recently, she was assigned to learn about a community institution and she selected her dance program. She made a diorama of the studio in a shoebox and interviewed the program's director. She voluntarily wrote five pages for the project, all on her own.

So what does she hate about homework? First of all, it's always the same. Second, it's totally rote. Third, she never gets to write or draw anything. Fourth, it's "really, really, really boring."

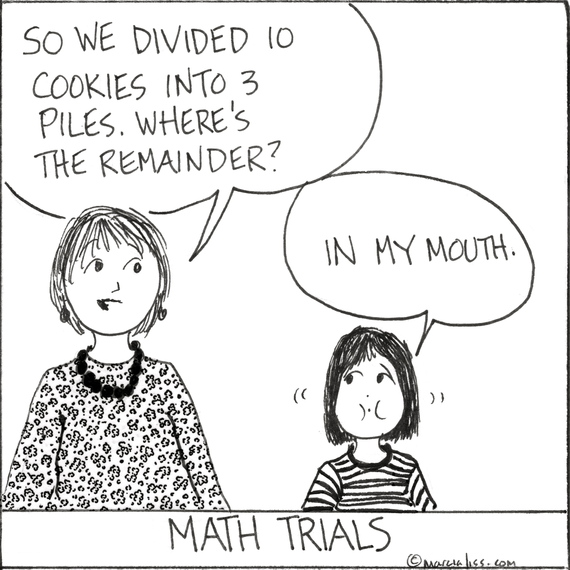

Cartoon by Marcia Liss, Huffington Post contributor

Her homework is always one or two math pages and a spelling worksheet. About that math homework -- don't get me started. When she doesn't understand it, neither do I. Recently, she had to take something in her house and divide it between three people. I grabbed ten mini-cookies, and she put them in rows. Then she counted and filled in the answer sheet. "Where's the remainder," I asked. "I ate it," she replied, "so I put zero."

Spelling is an example of homework that takes time while teaching very little. Even though she gets 100 percent on her spelling pretest, she is still expected to write the words in bubble letters and rainbow writing, type them on a computer, and put them in alphabetical order. Yes, keyboarding is a skill, as is alphabetizing. But she can do these things already. If the point is to spell them correctly, she knew that before she started. She would rather write a story using the words, but that's not a choice.

When my children attended grammar school in the 1980s, some homework started to appear in third grade, with expectations that children would write reports and complete long math assignments. At that time, being a former teacher, it was natural to become a teacher again and pitch in to explain or re-teach concepts that were unclear. I had to teach my children how to write in sentences and then paragraphs so they could actually write a coherent essay for the history or science reports that were assigned. So much for reinforcing what was learned at school.

Back then and now, I suspect, homework is also assigned as a punishment for the children failing to complete work in school, or for the class misbehaving. I will never forget one of my kids slaving over a difficult third grade assignment that consumed most of Thanksgiving Break, only to be told later that the teacher didn't really expect her to have done it so well. The homework was a punishment directed at children who were "goofing off" in class. Of course, those children simply ignored the assignment.

In recent years, homework is so accepted and expected that even very young children come home from a long day at school, have a snack and crack the books. Alfie Kohn writes about the negative effects of homework, especially when given to kids in lower grades. He feels it is stressful for children and parents, causing unnecessary conflicts over getting it done. It robs kids of time to spend with their families and to do other activities like play outside or draw.

In The Homework Myth, Kohn cites numerous studies that show homework to be of little value for young children. In fact, he believes it usually has the opposite effect of making them feel negative about their schooling and less inclined to do things that will enhance their education like reading for pleasure. In addition to limiting the sheer volume of homework, especially in elementary school, it is also important to consider the quality of what is assigned to children. If children are asked to complete assignments at home, at least make the work interesting, fun, and doable by the child.

Kohn sides with Dr. Lilian Katz, Professor of Early Childhood Education at the University of Illinois, who disagrees with vertical relevance, the notion that children need to do homework in early grades to "get ready" for doing even more homework as they grow older. This concept should be replaced by "horizontal relevance," which makes learning meaningful to children in the here and now because it relates to and builds upon their current life experience.

Trends in education come and go. The nature of homework -- at what age it should start and what it should ask of children -- will continue to evolve. For now, perhaps we should want something better for our children than subjecting them to the same pressures that make our lives so hectic and stressful.

Please take a few minutes out of your busy day to ponder the words of John Holt, educator, author, and advocate for school reform. Although I am not a home schooling proponent as he came to be at the end of his life, I think there are some powerful lessons in his books.

I have somehow missed the chance to put much joy and meaning into my own life; please educate my children so that they will do better.

If homework cannot be joyful, can it at least be meaningful? And at what age should we expect children to start doing it?

I invite you to join my Facebook community and subscribe to my monthly newsletter.