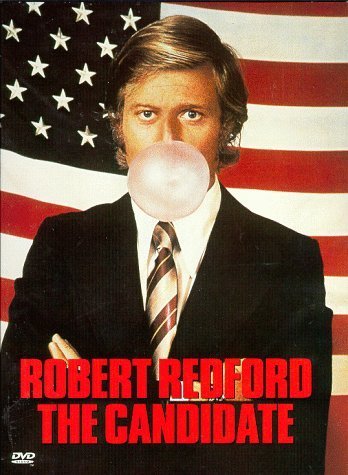

"What do we do now?" -- Bill McKay (aka Robert Redford), The Candidate

One of the big races this November is the campaign for mayor of New York City. This race is worth watching not because it is close (it isn't -- the Democrat, Bill De Blasio will win by a landslide) but because it is indicative of one of the real problems in our electoral system -- we judge candidates not on their fitness to serve but their ability to campaign.

If you haven't been paying attention, the Democrat De Blasio -- former public advocate and manager of Hillary Clinton's race for the U.S. Senate -- is set to win by a landslide. His incumbent is the beleaguered Republican and former deputy mayor of the city, Joe Lhota.

By almost any objective measure, Lhota's record trounces de Blasio's when it comes to experience. Lhota not only served as head of the MTA and as a deputy mayor under Rudy Giuliani, but he held both posts during times of crisis. In fact, Giuliani credits him with "keeping the city running after 9/11." Lhota has gotten as close to doing the job of mayor as anyone could without being an incumbent -- and, by all accounts, he did it successfully.

Compare that with de Blasio's much thinner record. His first major managerial experience was leading Hillary Clinton's campaign for the Senate in 2000. But, as David Chen noted, in this role he was "frequently indecisive [and] could be agonizingly inefficient in a high-pressure, ever-shifting situation." Things apparently got so bad that de Blasio was eventually replaced. His only other consequential experience is his heading the public advocate's office, which has about two dozen employees and a budget of less than $3 million. By contrast, as mayor, de Blasio will be in charge of more than 460,000 employees and a budget of almost $70 billion.

Lhota and his team bear responsibility for not making this case about the experience and readiness gap more forcefully. But the truth is, even if he had done a better job on the campaign trail of selling his experience and readiness to be mayor, it probably wouldn't have mattered. The reality of campaigns in the U.S. -- not just this one -- is that voters aren't that interested in these sorts of mundane things. We saw this most recently in the 2008 campaign for president when Hillary Clinton tried to argue that she was better prepared to serve than Barack Obama. Democratic primary voters largely tuned the argument out, opting instead for the arguably less experienced candidate with a message of change and an optimistic vision for the future.

That lesson wasn't lost on De Blasio. He has taken more than a page out of Obama's 2008 campaign manual: He has hired members of the Obama team, all of whom learned the lessons of 2008 well and applied them successfully in 2013. What both de Blasio and Obama understand is that campaigns are usually not won by selling managerial skill, experience, or expertise. The truth is, in American elections, experience and a proven track record don't count for much. Few voters will be moved by a candidate who proclaims the ability to manage large complex organizations. What does move voters is a call for change -- a change in specific program, policy, philosophy, or style -- as well as the promise that better days are ahead.

We have an electoral system that asks people to excel at certain skills. Like Obama before him, De Blasio has done that; Lhota has not. The question is whether the skills we ask our candidates to exhibit on the campaign trail (such as shaking hands, debating, giving speeches, raising money, selling their vision, etc.) are really those they will need to succeed once they are in office?

What does it really take to be mayor of New York City or president of the United States? Are we measuring the candidates based on those criteria or something else entirely? If the answer is the latter, we are destined to keep getting officials who are very good at campaigning, but perhaps not as skilled at governing.