What Donald Trump Teaches Us About How We Become Americans

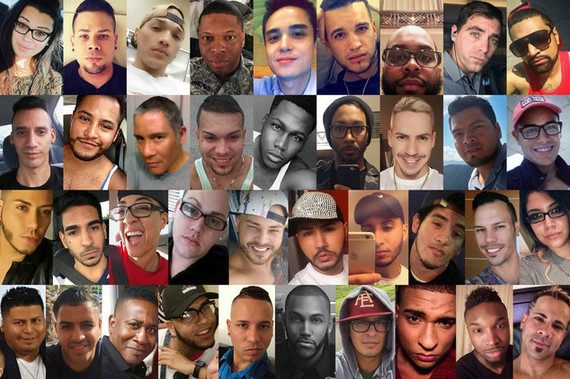

Grammar made the news this month, pushed into the spotlight by Donald Trump's renewed campaign to limit the terms of American citizenship. In the wake of the Orlando shooting Trump reaffirmed his pledge to stand strong against "the Muslims," promising not only to keep out those seeking refuge from distant shores but, more ominously, to monitor Muslim families already living in the United States. "They have to work with us," Trump pronounced the night after the tragedy, speaking to a crowd in New Hampshire.

"They have to cooperate with law enforcement and turn in the people who they know are bad...They knew the [the shooters in Orlando and San Bernardino] were bad. But you know what? They didn't turn them in."

To his adherents in the audience there was no confusion in the choice of language. The power of Trump's rhetoric lay in the deliberate placement of pronouns: They, set against us. Us, not we. On either side of each sentence, between the teleprompter and the candidate, Trump diagrammed permanent division, a forever abeyance of citizenship for American Muslims, a community reimagined for the purposes of the election as native informants in the twilight struggle against radical Islam. That the Orlando shooter had been born American, born as one of us, to immigrant parents in a Queens hospital not far from where Trump's own immigrant mother had given birth, made no difference. Islam presented as a special case, a pathogen carried by immigration, passed on genetically across generations. They could never become us. "I'm talking about second and third generation," he mused to Sean Hannity, "for some reason there's no real assimilation...[The shooter] was born here. His ideas were not."

The same might also be said about Trump, whose campaign to restore American greatness employs a blood-and-soil nationalism never before seen in modern presidential politics. Trump would make America European again, his proposition that surname and place of parental origin serve as fixed tests of national loyalty a localized version of herrenvolk democracy espoused by far-right parties in the UK and on the continent.

Trump's barely concealed skepticism that non-European immigrants can become fully American, what Dara Lind has described as a "zero-sum identity game," runs counter to core and native myths of what makes America great. If there is an American exceptionalism, it is in our namelessness and rejection of personal detail, in the belief, if inconstant practice, that where we come from has no bearing on who we can become. Michael Walzer once wrote that in the absence of a common ancestry or an ancient homeland we become Americans anonymously, our symbols and ceremonies invented rather than inherited from a particular place, "the flag, the Pledge, the Fourth...are, as it were, all we have." The script prepared in advance, the arriving immigrant needs only to learn her lines, meet her marks, and recite the part.

In fact, the new American debuts without rehearsal or direction, an improvisation performed, at least for a time, badly. There is no prepared text, the story written on the go, without beginning or end. The truth is that we arrive not knowing what to say. Assimilation occurs in the crucible of an ordinary life lived in trial and daily error, far away from global struggles or religious crusades.

It begins in the futility of the fast food drive-thru, in an order placed over and over again into the speaker, accented and unable to be understood by the scratchy voice on the other side. America takes place inside the sit-down restaurant, in the negotiation of a menu by sons and daughters who, better with the language, order on behalf of their parents.

We become citizens in the classroom explanation, foreign children made interlocutors for an entire country, religion, or race by what's in the news: Impromptu lectures in a Peoria kindergarten by the Iranian student on why Americans were being held hostage in their own embassy, a mini-seminar on religious persecution in sixth grade social studies led by the Yazidi refugee in Lincoln, the itinerant student from Michoacán anxiously explaining to his classmates the contents of his packed lunch.

Citizenship emerges with the impromptu staging of national holidays, in the fearless mix and match of ritual, Vietnamese Thanksgiving, Ethiopian Fourth of July, tahdig placed alongside the turkey, pho served before the Easter lamb. It takes place on the first tour of Halloween, when my mother and I held our neighbors at bay with a take-it-or-leave it demand: "Tricky tricky! Tricky tricky!"

We are met along the way by the Americans who were already here, their citizenship affirmed in the encounter with ours. "Son, it's not 'tricky tricky.'" Our hallway neighbor gently corrected my technique, slipping an extra handful of chocolate into my bag. "It's trick or treat." We do not singly become Americans. We become we.

American exceptionalism begins with the pronoun, a grammatical fiction that can draw out the better angels of our nature as well as lead us into bigoted temptation. "When we talk about [who gets to come here and call our country home] in the abstract," President Obama warned in a 2013 address on immigration reform, "it's easy sometimes for the discussion to take on a feeling of 'us' versus 'them.' And when that happens, a lot of folks forget that most of 'us' used to be 'them.'"

The Trump campaign thrives on the distribution and division of pronouns, on the easy difference between "us" and "them." Pronouns are an abstraction in Trump's hands, held "like a box with a false bottom" that allows him to "put in it what ideas [he] pleases, and take them out again without being observed." Trump wastes no opportunity to fill those boxes with falsehoods, doing so in plain view, suggesting that American Muslims condone Islamic extremism when they do not, warning that immigrants do not adopt American customs and activities, although the evidence shows that they do.

There is, of course, nothing new in the story that Trump is selling, nothing original in the nativist impulse to deny new generations the privileges of the old. For all of his spontaneous behavior on the stump and campaign trail, the naked celebration of "common sense" and political incorrectness, Trump represents one of the most constant tropes in American politics, the notion that the new American is somehow fundamentally, permanently, different from the old.

Few are buying it. Recent poll numbers suggest that that a growing number of Americans view Trump for what he is: A showman who has lost the plot. Nearly half of Republican voters want Trump dumped from the ticket, including an unprecedented 65 percent of all voters in Utah, a state that has not voted for a Democratic nominee in 52 years. As the country becomes more varied and diverse, as it becomes more American, our script deviates from his, more so each day.

"He doesn't know how to speak properly." My immigrant mother delivered her judgment in translation, rendering into English a sentiment borrowed from her native Iran. Forty-one years as an American had taught her something of the national grammar, of what was beyond the pale. This man doesn't know how to speak properly because he lacks decency. Translated from the Farsi, the sentiment was, from the first, already American.

Shervin Malekzadeh immigrated with his parents to the United States from Iran in 1975. Formally a professor at Swarthmore College, he will be a visiting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania's Middle East Center starting this fall.