Wearing a fitness bracelet from FitBit, Jawbone, Microsoft, Withings, and others has become increasingly common. About one in ten people in the US now do some sort of fitness monitoring.

As we become more comfortable with the idea of monitoring our own footsteps, calorie-burn, sleep patterns and other health indicators, we should be mindful that it's more than just individual data that's being collected. The companies behind these inventions are also monitoring and analyzing the collective data they are acquiring. What are companies looking for and why?

I spoke with Alexis Normand who oversees the Withings Health Institute. The Institute has created an Observatory which offers a view of the cumulative data of all Withings band wearers, free to the public. Much of the data is displayed in real time as it's being collected.

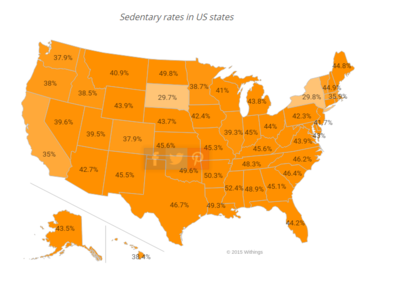

Recently, for example, the company's Observatory showed that Withings users in NYC and DC were the least sedentary of all American cities. It also offered a real time look at obesity (pictured below), with North Dakotans being most obese in the US.

Of course, conjecture and analysis help look at why certain cities score differently. After conducting an analysis of activity levels in nine major cities, Withings learned that Moscow clocks in with the highest number of steps during the workweek (7610 average steps) and that Madrid is a close second reporting 7512 steps per day. Madrid and Moscow are both known for their nightlife, a possible explanation for increased activity levels.

Withings is not alone. Apple's HealthKit (supported by Withings and most other activity trackers) is busy soliciting participants for clinical studies and recording a vast amount of data from users of the Apple Watch as well as other bands. Some of the data will be made public.

According to Jawbone user data, people in Tokyo sleep the least number of hours a day, while residents of Melbourne sleep the most. They turn in for bed earliest in Brisbane and stay up latest in Moscow.

Who cares? Public health officials, legislators and the medical community to name a few. Weight, along with high blood pressure, tobacco use, hyperglycemia and a lack of physical inactivity are leading causes of death. While a fitness band doesn't directly measure all of these things, it paints a picture of overall health.

This is the world of user-generated health information. By tracking our own bodies and donating the data to a growing pool of information, we are speeding up the process of understanding the many factors and variables that contribute to wellness.

Normand says that in the past, most data has been collected from two groups: athletes, and those who are ill. As the use of fitness bands and equipment usage spreads to the general population, we'll get a clearer picture of the practices that lead to good health. Data is a public health miracle.

After hearing about the results of Oklahoma City's rankings in these data collections, the city's Mayor decided to tackle his city's obesity problem. Standing in front of an elephant cage at the zoo the mayor announced he was putting the city on a diet-- together they lost over a million pounds.

"The research community is starved for data," says Normand. "Better data about health empowers individuals, but it also empowers those looking for comprehensive public health solutions."

Today, user-generated data collection and analysis is still in its infancy. Each fitness product generates its own data. Consumers are a bit leery of what companies and governments will do with this data. But over time, data from our fitness wearables will help determine best health practices, and will most certainly improve our quality of life.

Robin Raskin is founder of Living in Digital Times (LIDT), a team of technophiles who bring together top experts and the latest innovations that intersect lifestyle and technology. LIDT produces conferences and expos at CES and throughout the year focusing on how technology enhances every aspect of our lives through the eyes of today's digital consumer.