I am serializing an unpublished book in this column. It's about an amazing, mysterious manuscript I discovered in Scotland. It's a little book with nothing in it but 50 watercolor paintings. No one knows who painted it, or when, or where, or what it means. I was so entranced by this that I wrote a whole book of comments and thoughts on it. I call the book What Heaven Looks Like because the person who painted this was dreaming, I think, of an ideal world, a kind of heaven.

You can read the first installment here and the second installment here, if you want to: but if you're coming in late, no problem. No one knows what this book is about, so you can suggest your own ideas, and we can build a collaborative interpretation.

I am collecting people's suggestions, both here and on Facebook, and I am going to put them -- with full credit of course! -- into the book when it's published. So feel free to add your ideas.

Several comments to the earlier posts are especially intriguing: one person thinks this is really a book about hell, not heaven, and about psychosis, not meditation. Another person says that these pictures are like looking up through water, or down into water. I agree with parts of those ideas, and many other ideas people have posted. Thanks so much, everyone!

7

That (the previous plate -- see last installment) seems to be the end of the first story about heaven and earth. This plate starts something new: landscapes where interesting events are unfolding.

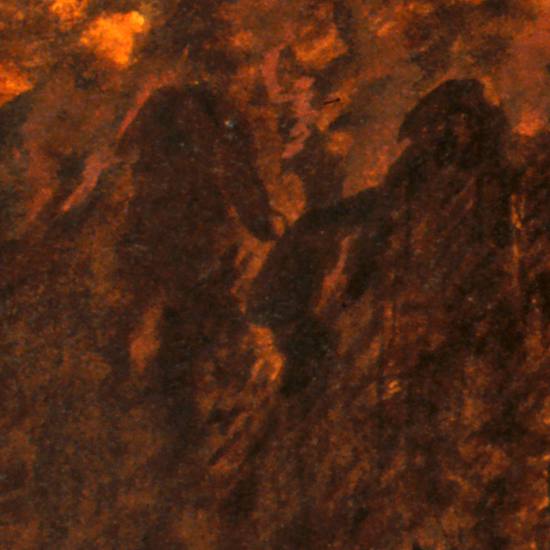

This is a sulfurous, volcanic place that seems to be on fire. The sky is choked with dusty clouds, and it shimmers with heat like the inside of an oven. Even the earth glows as though it were stoked with embers. In the middle is a heap of rocks, freshly congealed from lava.

In this infernal place -- could it be Hell? -- there stands a holy figure. He has a beard and the mitred hat of a bishop. A man kneels in front of him and crosses his arms on his chest. The bishop is holding something. It may be an open book, but the two pages are canted at angles to one another, and so they could also be the tablets with the ten commandments. The bishop's arms are not in the right position for holding a big book (which would be grasped by the sides, not the bottom); but on the other hand no Catholic bishop should be holding the ten commandments. If it were Aaron bowing before Moses, that would make sense, but of course Moses was never a bishop. Through a famous misunderstanding, Moses was often painted as if he had horns, and that may have been the artist's first thought before she turned them into a hat. I take she wanted the paradox. But what could it mean?

There is no help to be had from the figures at the left. One leans back, recoiling from laughter or astonishment. The other points up into the rocks, and if we follow his gesture, we find people there.

These are very shadowy creatures, the hardest to see of any in the manuscript. One scampers up the hillside away from the man who points. It has a funny hat, perhaps with sharp corners. The others are fused to the rocks themselves. A large figure seems to stand to the left of the fleeing one; it looks headless. Another vaguer figure remains locked in the rock up where the scampering figure is climbing. There may be more, but the artist has made sure we cannot see them.

In the library in Glasgow, this book is in a collection of alchemical manuscripts, and the artist does sometimes draw on alchemical themes. This may be such a case: there is a tradition in alchemy of the "planetary mountains," places where the earth produces mercury, sulfur, gold, and the other metals and stones. The planets and the Greek gods were used as symbols of the metals: the planet Jupiter, for instance, stood for tin, and so a picture of a hill with Zeus on top meant the metal tin. Parmigianino, the renaissance artist, made pictures of such mountains, and this looks a little like his work.

What happens here, though, is much less literal. These are mountain spirits, not gods, and nothing is being explained about metals. This is the "universal Catholic" nature, the world pervaded by inexplicable continuous creation. To understand it, an adept needs knowledge of metals and knowledge of the divine purpose -- whether it comes from the Old Testament or the New.

8

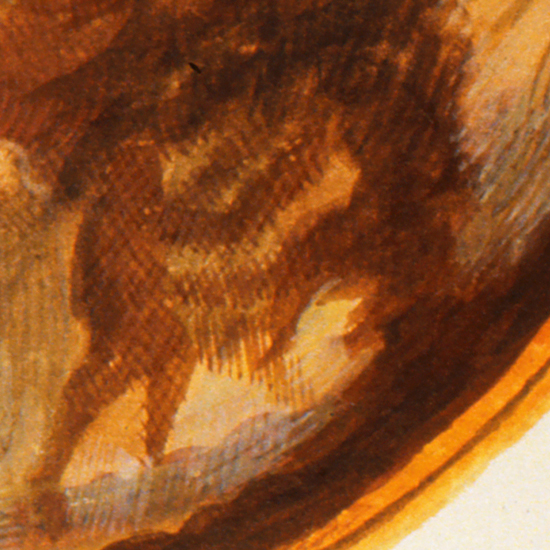

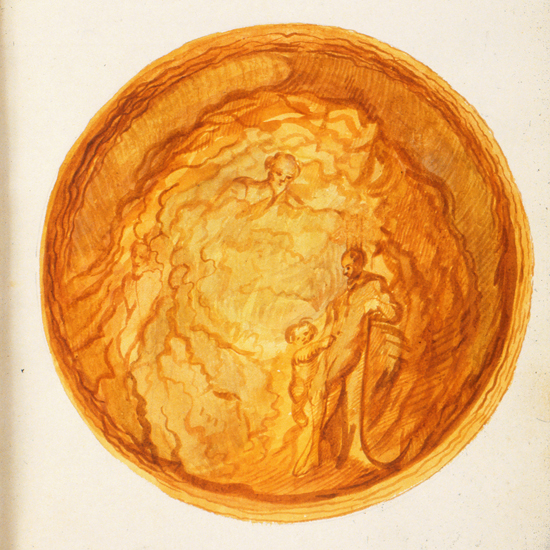

Now the landscape has shrunk and we are looking at just a bit of it, cut off from the rest like the weightless planets in The Little Prince. Viewers back in the seventeenth or eighteenth century would have thought of cameos and carved gems, and we might think of coins: the figures and their scrap of rock float against a round backdrop, like the embossed head on a coin on its field.

This time the action centers on a boy who is running across the scene and gesturing in a somewhat operatic manner. His pose might well have reminded people of Hermes (who was a messenger and a guide, and so was always running). There were statues of Hermes in more or less this pose, and in paintings his clothes tend to billow the way they do here.

But there is plenty of room for uncertainty. Although it is clear that he is borrowed from painting or sculpture, it is not as certain that he is Hermes. At the least, he should have wings on his sandals, and normally he also carries his trademark attribute, the caduceus (snakes twined around a staff, the emblem of the medical profession). His cloak flies out in front of him and is caught by a woman, and the two of them together might well have reminded people of Venus and her disobedient son Eros.

Once again, there are two meanings that seem incompatible, and again, they fit together like the front and back of a single coin. If this is Hermes, he represents one of the alchemists' favorite metals, mercury. Mercury was said to be "volatile": it runs everywhere, and even evaporates into thin air. If it is Eros, the same ideas apply: Eros (who stands for sexual desire) is unpredictable: anyone might be the target of one of his arrows, and he even stung his own mother.

All this makes some sense: it's a meditation on uncertainty, on things that cannot be pinned down, on fleeting thoughts and desires. At least that is what it would be if this were a normal painting. But in this book, it might be something entirely different. This could be just a woman and her son, playing. And it is important not to forget the fat dragon who lies on top of the rock, wagging its big tail and sticking its toothy jaw right in the woman's face.

9

That dragon (in the previous painting) may seem gratuitous, and it makes no sense I can think of. Yet it would slight the artist's achievement to say that she just stocked her paintings with whatever came to mind. The dragon is very deliberately painted. The hatchmarks that go round the plate stop at its tail, and resume on the other side. Its body is clearly segmented (like a worm's) and it has a cute little plume at the back of its head. The details are carefully balanced; the dragon's feet, for instance, may once have been more detailed, but the artist has masked them in dark umber tones. I think there was originally a figure to the right of the boy, but whatever was there has been painted out. The scene has all the traits of something that grew slowly and organically in the artist's mind, and was only finished when it reached a pitch of perfection. Even a blatant non sequitur like the overweight dragon has its value. It says, in effect: You will never understand this picture. And that, I think, is a wonderful and deeply modern frame of mind.

Here is an even less comprehensible arrangement, an impression of more disturbed thoughts. In the middle a gigantic bear holds a tiny man's head in its mouth. They are floating in a swirl of visceral globular shapes, as if the painting is a view into intestines, and the bear's head and man's head are both being digested by some even larger animal. (Stepping back, it is a gnarled stump or root: but it is always a question of how far back we went to step.)

In the lower-right corner a man steps up to a seated figure (probably a woman) and offers her something, or takes her hand. The little vignette would be a love scene, if the woman were a little more real: she is a slightly frightening blur, and she reaches out to the man with long hazy legs -- more like a spider perching on its prey than a person shaking hands.

This is a gloomy and threatening painting, and that mood is perfectly congealed in the second bear's head at the upper left. It has a glassy blue eye, and it seems to brood over the scene with amused detachment.

10

The habit this artist has of looking into stumps and finding fantasies was not original, but other people found stories that were obvious, and therefore comforting. There was a custom of cutting stones -- especially marble and agate -- and finding pictures in them. For a while in the seventeenth century it was said nature sometimes started a painting inside a stone, but left it unfinished and artists would add figures and reinforce shapes to make simple landscapes or mythological scenes. Certain rocks, called "picture agates," were already so similar to landscapes that they were considered finished paintings. In the previous century, people had prophesied by finding shapes in deformed animals and in the gnarls and burls of trees. Nature painted and sculpted, and people tried to understand what she meant. But in every case the things they thought she meant were simple: a prognostication of war, a bucolic landscape, a portrait of the Pope. Here all that has been given up, and it seems trivial. Nature speaks much less clearly in this book. The artist is looking as closely as she is able, and setting everything down in its place: but the results are disquieting, and they often verge on meaninglessness.

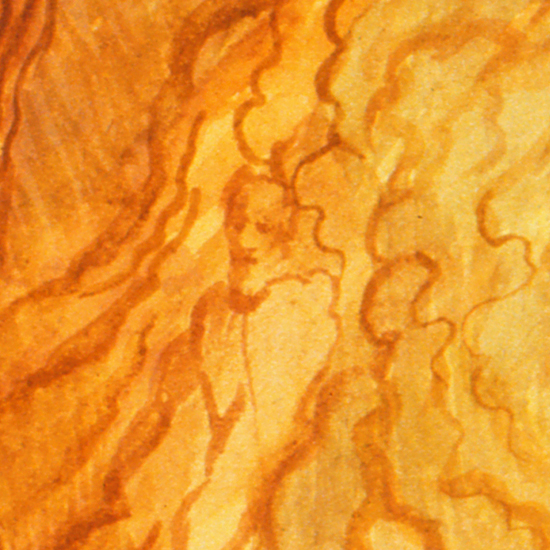

This time she sees a figure of Saturn with his scythe, looking down absentmindedly at a little boy who clings to him. The man could be Saturn or Father Time -- the two were occasionally interchangeable -- but either way he is significantly less fearsome than usual.

The scythe, after all, is for harvesting souls. Saturn and Eros were sometimes paired, and perhaps the artist was thinking abstractedly about Love and Death.

This artist has a sweet, familial streak in her, and she has soft dreams as well as terrifying ones. Here it's as if Saturn were in retirement, thinking over a day's work -- or as if he had become a simple peasant, whose scythe cut wheat and not people.

The pair are illuminated by a golden light from behind (notice the elegant shadow cast by the boy's foot). In the cloudburst there is an even more comforting figure, very much the kind that people painted in cut marble. He is a benevolent old man, possibly also God himself, looking down on his work. And at the left, another old man, gazing out of the scene. All three men look the same: perhaps the artist was a man after all, and these are three self-portraits, versions of himself made on a day when we was thinking more about the passing years of his own life than about the miracles of nature.

Next installment: one of the strangest pictures painted before the twentieth century.