Although I've devoted my career to teaching entrepreneurship, I've been a physics fanatic ever since I was a precocious 11-year-old with an unusual gift for math and science. Today, I would probably have been diagnosed as being somewhere along the autism spectrum, but back then my gift was just considered a bit unique. Moving to Princeton last July fulfilled a lifelong dream in part because ever since childhood I've been fascinated with the bucolic Institute for Advanced Study, where such geniuses as Albert Einstein, John Von Neumann and J. Robert Oppenheimer received the support and latitude to conduct their research and wrote groundbreaking books and articles.

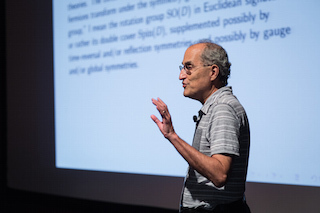

During the IAS Prospects in Theoretical Physics program. Photo credit: Dan Komoda

One of the first stored program computers was designed and built on the Institute's campus with von Neumann architecture that greatly influenced the development of today's computers, and formed the mathematical basis for computer software. The foundations of game theory, a powerful tool in economics, were laid in the School of Mathematics at the Institute, and research at the School of Natural Sciences has greatly advanced particle physics, including string theory and astrophysics.

The Institute for Advanced Study's mission to support pure research makes it all the more admirable to me. I also believe that research done at the Institute for Advanced Study contributed significantly to American victories in both World War 2 and the Cold War, thereby saving civilization from totalitarianism and tyranny. Even John Nash--the Nobel Prize-winning economist portrayed in A Beautiful Mind who sadly passed away earlier this year--spent time in the 1950s and 1960s there. It is impossible to quantify the good this incredible place has done, and will continue to as it encourages and supports scientists from all over the world who come to Princeton to share ideas and collaborate. One key benefit to continued research into quantum physics, for example, is that it holds the potential to forever solve the world's energy problems by enabling us to create energy far less expensively, which would improve all our living standards enormously.

So, this summer I spent two weeks of my vacation attending the Prospects in Theoretical Physics program. The first week was held at Princeton's Fine Hall, where the university's math department is housed, and the second week was at the Institute.

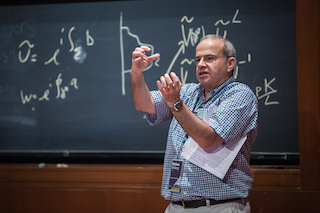

Nathan Seiberg at the IAS Prospects in Theoretical Physics program. Photo credit: Dan Komoda

What a wonderful opportunity this was to be among an inspiring community of scholars, including roughly 200 of the world's top post-doctoral students in theoretical physics! The presenters were inspiring, charismatic and exuded passion for their fields. I could feel the energy in the room. The global talent represented was truly impressive.

The Institute is a very convivial place, and most of my new friends at Princeton I have met at Institute luncheons. I enjoyed the daily lunches with students and am sure I'll stay in touch with several of the post-docs I met at the conference.

On a personal level, spending time at the Institute has not only reconnected me with my long-lost passion for quantum physics, it has also reminded me of a childhood encounter I had with a certain redheaded physicist.

In 1964, my parents and I were vacationing at the Isles of Shoals off of New Hampshire. My parents, who were lifelong educators, made friends with a tall redheaded man named John. Kind and funny, he had a striking Irish accent, was living in France and worked at CERN, which I had learned about from my father.

Edward Witten the IAS Prospects in Theoretical Physics program. Photo credit: Dan Komoda

John told us that he was on sabbatical, and had been at Stanford, and then Wisconsin, where he had been working on a paper on an error he believed Von Neumann had made in his legendary textbook Mathematical Foundation of Quantum Mechanics, in which Von Neumann had stated (incorrectly in John's opinion) that "quantum mechanics does not permit a hidden variable interpretation" (p325). John told us he was on his way to Brandeis to finish a second paper, a comment on the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paper, before his sabbatical ended and he had to go back to work at CERN.

I was instantly awestruck, and although he was only on a day trip to the Isles, John very kindly took an interest in me and offered to show me some pointers in quantum physics, as I had been auditing a course at the University of Michigan that was way over my head. He showed me some very basic math he was planning on using in his next paper, and talked to me about the interconnectivity of particles and how he believed that someday we would find that everything is interconnected, including our minds.

My once-strong abilities in math and physics faded as I grew up, and instead I devoted my career to entrepreneurship education for at-risk youth. In my capacity as NFTE's founder, I often traveled to Davos to speak at the World Economic Forum. On one such trip I met a physicist who told me about the Einstein Museum in Bern. I visited the museum the very next morning, and fell in love all over again with my childhood romance: physics.

Nathan Seiberg, during the IAS Prospects in Theoretical Physics program. Photo credit: Dan Komoda

I enlisted my brother-in-law Michael Schmidt--who was head of the physics department at Yale and had also been on one of the Particle Teams at CERN--to help me get caught up with quantum physics. The first thing he had me read was John Bell's paper "On the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox," published in 1965 by the short-lived journal Physics Physique Fizika.

To my surprise I recognized some of the math in the paper, and I have believed ever since that the kind physicist who made time to tutor me in the summer of 1964 may have been John Bell himself. Now here I am living in Princeton, where I was recently allowed to enter the Institute's archives and read a copy of John Bell's seminal paper in which he laid out his famous "Bell's Theorem." I have to admit that seeing it brought me to tears. I felt in that moment confirmation of the belief I have held ever since meeting him the shy genius as a child that, as he told me, "everything is connected and nothing is wasted."

Robbert Dijkgraaf at the IAS Prospects in Theoretical Physics program. Photo credit: Dan Komoda

If you are interested in physics, you might start with the book Quantum by Manjit Kumar, which provides a very clear overview of the current debates in physics. If you feel inspired to dig a little deeper, check out my column Curious About Quantum Physics? Read These 10 Articles!

John Bell Lecturing: