Last month, at the age of 71, after 41 years in solitary confinement, and less than three days of freedom, Herman Wallace died of cancer in Louisiana. He once asked me: "Why would you be my friend? Are you forgetting that I don't believe in God?" I don't know that I answered his question, but I was struck by the depth of friendship he expressed in one of his letters: "You are my friend, in my heart, all because you looked past the color of my skin, because you looked past the bars that physically separated us, and foremost, never once did you judge me."

Herman Wallace was a Black Panther, a political prisoner, and he was my friend.

Herman Wallace was convicted in 1971 of armed robbery in Louisiana. He was part of the Black Panther movement. If you talk to some - the Black Panthers were viewed as militarized anarchists who wanted to "deliver black people" from oppression while turning the tables against white power and the political establishment. If you talk to others, the Black Panthers were the ones who protected kids at the crosswalk in inner city Oakland so children could get to school safely. In 1968 they were classified as a hate group and deemed ""the greatest threat to the internal security of the country" by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. If a movement is deemed that threatening and scary even in cities like Los Angeles and Oakland, you can imagine how people in Louisiana would have responded.

So when in 1971, 29 year old Herman Wallace, as a participant in the Black Panther movement, held up a convenience store at gunpoint, the repercussions were severe. Wallace was sent to serve his sentence in Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, notoriously the bloodiest prison in America. So much so that in 1952, 31 prisoners sliced their Achilles heals to draw attention to the atrocious conditions. In 1974, Wallace, along with Albert Woodfox, was convicted of the murder of Brent Miller, a prison guard at Angola. Wallace served the majority of his sentence in solitary confinement.

I first met Herman Wallace in 2005 during my first trip to Angola as the leader of the prison ministry at Willow Creek, my church at the time. I was taken aback by our encounter. After 33 years of solitary confinement - 23 hours a day in a 6' by 9' jail cell with an hour a week outside - Herman was sharp in mind, engaging with questions, and deeply committed to ideologies of black liberation and freedom.

Herman once told me: "In order to be liberated we must first liberate ourselves." As a Christian, I believe my liberation comes from faith in the person of Jesus Christ. The way I, and often the Christian community around me, overlook the humanity of individuals like Herman and leave them out in the cold is a sin from which we need liberation. I am so convicted that the body of Christ must allow our hearts to be broken and repent of the ways that we have not responded to the needs of both victims and prisoners, how we have not been advocates of both love and justice - and from our repentance - I believe that God will help us discern what we are called to do to engage. And engage we must.

As a follower of Jesus, I wish that I were better able to love. In Herman, and other prisoners in the United States and around the world, I see a population of men, women, and children who have been rejected by society. In the United States, the makeup of those prisoners is predominantly black men. They face the consequences, often of their own poor decisions and actions, which further isolate them from society and reject their very humanity. The prison system often makes things worse as it has become increasingly punitive rather than rehabilitative. Our common idea of how to treat prisoners can be pretty much summed up in the idea of "just lock them up and throw away the key." Once someone commits a crime, it is almost as if they have lost their redemptive potential; they are no longer human, no longer worthy of love, respect, and the opportunity to change, grow, and experience forgiveness.

As I reflect on Herman's death, one of our particular encounters in Angola comes to mind. It was nearly six years ago on November 1, 2007. I was leading a ministry team from the church where I was serving as an executive pastor in California. One of my travel companions was Debbie Blue, the national leader of Compassion, Mercy, and Justice for my denomination. She and I had the opportunity to visit with Herman that day. Usually when I speak to inmates, my hope is that they might experience the love of God through a "ministry of presence." I don't think it is my job to beat them over the head with the Bible, as many of them know the Bible better than a lot of ordained ministers! However, I believe the love of Christ can be revealed by showing respect and entering into authentic relationship with one another. On this particular day, Herman was deeply interested in questions of faith. He led the conversation to talking about God, the person of Christ, and what it means for Jesus to be the liberator of our souls. Then he asked for my Bible.

For me, this was a profound question. What would this self-proclaimed atheist, convicted prisoner for life, want to do with my Bible? I also wasn't sure the prison guard hosting me would give permission for me to be able to pass the holy text between the bars. I was pleasantly surprised when permission was granted! Herman kept my Bible and in one of his letters told me a little more about what the experience meant for him:

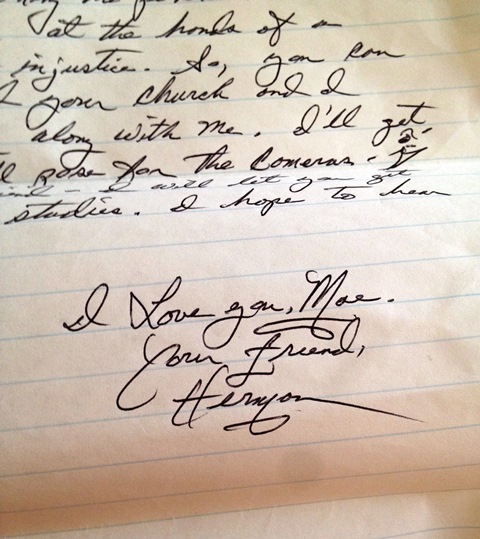

Let me explain our connection and then you can make of it whatever you like. I'm sure you recall my asking for a Bible. At that point you were quick to offer your personal Bible. I know it is dear to you because I see all of your highlights dating back to 2005. In our discussion Debbie challenged me on the next time I read a selected passage from the Bible that I should not read it with a fix opinion or to review it for any special purpose - but rather to allow the words to penetrate my soul. Ok, you do recall I promised I would. Well, I picked up the Bible and went straight to the back to choose a particular subject. My eye caught the word understanding - I looked under it and it referred me to Job 42:3 and so I flipped the pages to carry out my promise to Debbie. Upon that page were your markings - 11/1/07 - plus highlighting the blessing God gave to Job. You had to have done this shortly before your visit with me. Much of our conversation can be said to have centered around a similar subject. Out of 1,234 pages, how is it possible I could intentionally seek this particular page (498) of the very same message you were embracing prior to visiting me... How much more divinely connected could this be?

"You asked, 'Who is this that obscures my plans without knowledge?' Surely I spoke of things I did not understand, things too wonderful for me to know." Job 42:3 (NIV)

During Herman's 41 years in solitary confinement, his thoughts and writings often focused on what it means for one to be free. Certainly he was referring to the material freedom of being released from prison and not being confined to 23 hours a day behind bars. But he also wrote about freedom for the soul. He was determined that he would be released. He wrote of how he would take the message of his suffering around the world as an example of someone who suffered at the hands of injustice:

In anticipation of freedom, I am already booked to speak before Parliament in London - members of the ANC in South Africa, numerous schools in the Netherlands, and a few churches who have been instrumental in raising the consciousness of members of their community and congregations concerning the persecution Albert and I have endured at the hands of a corrupt system of injustice.

I do believe there are injustices within our criminal system. Even more so, I believe that poor people of color are often those the most adversely affected by the brokenness in our system. Michelle Alexander goes so far as to call the U.S. prison enterprise The New Jim Crow, the title of a book she has written about the deeply concerning ways the penal system adversely affects black communities and further perpetuates injustice. This brokenness is a great tragedy.

Herman's story reflects this tragedy. I am grateful for the judge's ruling that deemed Herman's 1972 indictment unconstitutional and allowed him to see freedom and sunlight before he died. I wish that I could have seen him, to say goodbye. I will forever be indebted to him for the things he taught me through his strength of character, his fortitude, and his personal quest for freedom.

As I think about what Herman might have said to me if we had the opportunity to say good-bye, the words he shared most often at our departure both in person and in his writings come to mind:

Mae, one day you will look out over your congregation and you will see me and my people sitting in the back of your church. I will bring company with me. And when you see me, then you will know that I am free.