Today, a conversation with author David Pace about the growing numbers of "ethnic Mormons," those who grow up Mormon, but for various reasons leave the church, and how Mormons may need to mage a bigger tent to include them.

1. When I first started to articulate some of my doubts about Mormonism with non-Mormon friends, they asked me why I didn't create my own church. Take what I loved about Mormonism and move on. Or find a splinter group that matched my own ideas better. It's a very Protestant view of religion, and I struggled to explain to them that the choices in terms of splinter groups were slim and grim pickings. As for creating my own church, growing up as Mormon meant that I had an abhorrence of "priestcraft," quite apart from my introverism and general disinterest in organizing large groups in any form.

David, what are your thoughts on this?

Protestants, God love 'em, would've recommended you jump spokes (or create your own). Seems like easy jumping from Methodism to Presbyterianism. Mormons would not be telling you this, however, because to date we as a people have lived in a closed and totalizing system. This is a good thing in that you have an instant community wherever you go--a group where assumptions are held tacitly and comfortingly. But it's bad when you finally figure out that you don't fit in, that you disagree with something. Where do you go then? As with political refugees, something that's very much on everyone's mind right now, you don't volunteer to leave your country because you can't imagine life apart from what you hold to be reality in your bones. There is no life outside the Mormon's observable universe, except a life that is compromised by not living in the light of Truth, with a capital Mormon "T."

2. Out of eleven children in my extended family, two of my sisters have now left Mormonism formally and one of my brothers is less active. But the rest are all some flavor of active. Watching many Mormons resign in the last few weeks, I have wondered how many will seek a new religious identity in other religions. It has been my (somewhat limited) experience that most Mormons who leave the church become atheists or leave because they are atheists. Do you agree with this? If so, why would this be? How do you think growing up Mormon forms an identity that tends to be black or white, in or out?

My experience with exiting Latter-day Saints is that they are left wandering and that it is often a tortuous wandering. Some do self-identify as atheists, as you mention. But many others affiliate with other faith communities. I resigned my membership in 1996 for reasons similar to what's happening right now in Mormon America, and I joined with my wife in her faith, the Episcopal Church. That was my "home" for 10 years. (I was an "EpiscoMo."). Still others, I think many, especially those who don't leave formally, will return to the ward because the only moral center they have been allowed to have is the collective. It's the result of pernicious paternalism. That's where the in/out and black/white thinking stems from. Since my exit, I have had to form (as opposed to adopt another) moral compass. It's been the most excruciating experience of my life. I wasn't willing to stop calling myself a Mormon, though for years, I didn't know why. That's when it occurred to me that there was a third option between in or out: secular Mormonism or what I've called ethnic Mormonism.

3. You've written about ethnic Mormonism, [Pace's foundational essay on ethnic Mormonism can be found here], an identity for those who grow up Mormon but no longer identify as active or believing members of the church. What does this mean? If you reject the truth claims of Mormonism, what is left? Stories from The Book of Mormon that become myths like Santa Claus? Is there more than that? Is it about the habit of Family Home Evenings, moving people in and out, jello salad and funeral potatoes as favorite foods, pot luck meals on lawns?

Ethnic Mormonism is all of that, and more. It's accepting that (spoiler alert) there is no Santa Claus (the LDS Church's truth claims, or at least some of them) but that the spirit of Christmas (the traditions, culture and even teachings of Mormonism) is a real and valuable thing that should be honored and preserved. We have a model for it in the fractured state of world Judaism, which I think is a blessed thing for Jews. Except for perhaps the fundamentalists in Judaism (the ultra-orthodox), Jews accept Jews of other stripes. It's time for that to happen for Mormons with its legacy of being a "chosen" and sometimes persecuted people historically, but also the standard bearers (for better or for worse) of a new religious tradition, not just a new Christian denomination. That said, it's not likely to happen too quickly. And maybe it shouldn't. There is a crucible (a gethsemane in Christian terms; "Liberty Jail" in Mormon terms) that a tradition and ethnic identity must move through. I'm proud to be someone who is bobbing around in that gumbo trying to get footing for myself and the people I still claim as mine.

4. Devout Mormons often think of former Mormons as being "unable to leave it alone." From within Mormonism, this is seen as proof that the church is true and that once you have left it, you either seek to disprove it as a gesture of self-justification or out of sheer evil, to lure others away from "The Truth." How do you reinterpret this?

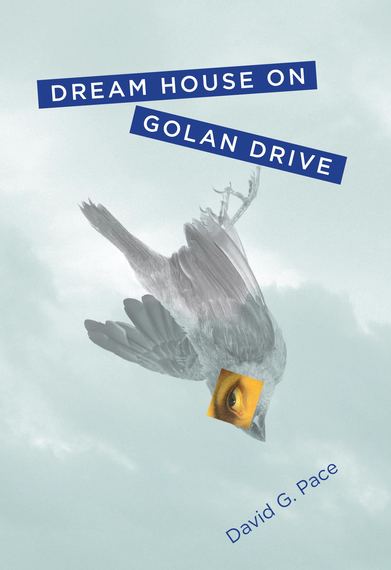

The genius of the LDS Church (if you want to call it that) is the paternalism I was talking about above. What results from that is a fusion of the individual to his/her family and the family to the institutional church. That's where the loyalty to the church largely comes from. Mormons don't know where their skin ends and (often) where the skin of their family of birth and church begins. That's why, as an orthodox Mormon, every time the church was criticized from within or without, I felt personally attacked. Of course Mormons can't leave their faith alone: it's their identity and it's their moral compass. In my experience, the church requires that you adopt through strict obedience the voice of LDS authority the collective (including LDS authority) as your moral compass. How does a Mormon in Transition navigate that? Very badly, I'd say. I have tried to recount this in my recently released novel, Dream House on Golan Drive. Very badly indeed. That's why I'm not particularly thrilled to see people leave their Mormon homeland. Instead, to put it metaphorically, they need to leave the Soviet Union while at the same time honoring and living for Mother Russia.

5. Can ex-Mormons and more conservative devout Mormons be allies? My experience within the church was that members are encouraged to stay far, far away from people who have left the church. Not just in the sense of avoiding associations with groups that work against the church according to the temple recommend question, but in a kind of fear of contamination. Ex-Mormons are far more difficult to stay friends with than people of other religions and perhaps not just because there is the hope of converting others who haven't already rejected our religion.

The short answer right now is no. Ex-Mormons and active, card-carrying Latter-day Saints aren't likely to be allies, or even friends. The most fearsome and damaging anti-Mormons are former/ex- Mormons, not the Evangelical hotheads who want to tear at LDS doctrines, and not the militant atheists and agnostics who, in my view, are just as fundamentalist as the believers they claim are deluded and even dangerous to society. There's a saying among those outside the LDS faith that Mormons make great neighbors, but lousy friends. That's because our people tend to be excruciatingly "nice" and civil, which is a good thing (they keep their lawns mowed). But they can't connect intimately with others who are not of the faith, in my view, especially because they are required to try to convert non-Mormons. That isn't intimacy, because, in my view, that isn't respectful of others. Remember active Latter-day Saints live in a closed system, inoculated from the world. Their lives lie totally within the program of the religion. Practically, the orthodox LDS and secular Mormons are going to have to start caucusing. There have got to be options for being Mormon other than being a card-carrying Latter-day Saint. And the common ground these disparate Mormon groups can meet on is the culture and great traditions of the Mormon Corridor here in the Rocky Mountains and elsewhere: the literature, the history, the mythologies, the customs and yes, even the funeral potatoes. That's why I applaud Mormon authors like you. You dignify the culture and the people, especially the heroine Linda Waldheim. And you do it by mining the culture and setting rather than the faith's doctrine itself.

6. Ex-Mormons sometimes complain that they lose their family and friends as well as their religion when they resign, but is this partly on both sides, because it is frustrating on the other side to see people making mistakes that you've come to see as perpetual problems with the organization itself. How much of the shunning is intentional from Mormons and how much is just lack of anything in common?

Currently, those who start coloring outside of Mormon lines do lose their family. I lost mine. I lost the respect of my friends, most of whom were and remain part of the fold. Because my family (which includes 11 siblings) is what Kendall White called "neo-orthodox" there is no meaningful connecting tissue between them and me any longer. That I've married a non-Mormon makes it even more onerous for both parties. We are loving with each other, but we are not intimate. Those of us who have changed the rules, like me, are the ones who have to help open up a space in which a broader Mormon community can emerge on its own. In my experience, devout Latter-day Saints do not have the tool kit to do that on their end, nor the motivation. Right now, they MUST circle the wagons as the majority are right now in light of the recent policy change equating gay parents with the term "apostate." Even so, devout Latter-day Saints grieve for their losses. But they grieve like a child or an animal grieves: uncomprehendingly. One must never dismiss the pain of another. But for the good of lapsed / or the currently lapsing Latter-day Saint, I and others have tried to identify ways they can manage LDS relationships. Consider a mantra I personally use for this enterprise and one that, incidentally, might help heal the current, seemingly intractable divisions in the United States: Stand your ground. Check your Fundamentalism. Compromise for the good of the collective. [Go here for Pace's example of how this might work for Mormons as they navigate the exclusivity of their temple wedding ceremonies.]

What this little verbal triptych means is that we need to stop just adopting the opinions of other individuals found on, say, Facebook and received from institutions, and instead start developing opinions and stances through critical thinking. Checking your fundamentalism means we all suffer from the disease of rigid and condemning thinking, whether we're religious or not, and that we need to keep that in check by acknowledging how each of us is implicated in the issue. Only if we do the first two can we functionally compromise for the good of the whole which is the best, most healing way forward. To be clear--for my Mormon brethren and sisters--"collective" can no longer mean just the institutional church.