Fifty-one years after Marshall McLuhan first wrote "The Medium is the Message," Paul Ford's 38,000-word magnum opus on programming embodies that vision. The print version of the story, which covers 72 pages in a special issue of Bloomberg Businessweek, strains the definition of "article." It's really a short book about computing, computers and culture, and an excellent one at that.

For readers who see that length and snarkily say TL;DR ("Too Long, Didn't Read"), Bloomberg produced a short video that condenses the main thrust of the massive feature into three minutes.

What this piece was fundamentally meant to do is help the public answer the question about what code and coding are and what they mean in today's world.

"It's not obvious to people when they look at the web that every bit of text, every block, every graphic can be cracked open," said Joshua Topolsky, the editor of Bloomberg Digital and chief digital content officer of Bloomberg Media, in an interview with The Huffington Post. "This story gets into the code of what coders do and why they're so powerful. One of the coolest things is explaining to a reader who doesn't get this subject that all of this stuff is malleable. Nothing is what it looks like: it is code, and being able to show it, so clearly and visually, is magical."

The way this piece works is quite intentional, going back many months to when Ford and Josh Tyrangiel, the editor of Bloomberg Businessweek started talking about how to present the article online. The idea for the article was proposed over a year ago, Ford said. The first draft landed in July 2014, at almost 10,000 words, and grew and grew as the editors asked for more. On the Web side, a team of two editors, two developers and a designer were dedicated to working on the code behind "What is code?" for the last month.

"This is about understanding a mindset, and that then led to a feature set and characters," Tyrangiel said. "It's much less about 'learning to code' than seeing how characters interact."

"Think about what happens when you type the letter A," he continued. "You probably never thought of all of the functions that go into code. That then informs what interactivity should be: It helps get across what he's meaning. It's not feature sets for the sake of feature sets, but [for] the sake of telling the story."

The online version of the story integrates interactivity in unexpected and delightful ways. Spanning text and video, the dominant media of the 19th and 20th centuries, the result is a story about software built using software, augmented with explanatory elements about how software works. Combined with Ford's narrative, the sum total works better on that level that anything else I've seen before online. I should disclose here that I have a personal connection to the author: Ford was one of my father's university students, although I didn't meet him in person until more than decade later, at an O'Reilly Media conference in 2011. We realized then how we were connected and have stayed in touch as his writing career has blossomed.

To publish a 38,000-word article online in an era where capturing and holding attention has become more challenging than ever might seem like a risk, but it was clearly a calculated one, based in no small part on Ford's writing history. Three days after launch, it looks worth it: the code story was the most popular article on Bloomberg's website on Thursday and Friday, with people spending much more time on it than the average article.

While Bloomberg declined to give hard traffic numbers, Topolsky said that traffic was "very, very, very healthy," with engagement time on the page "really high" compared to their norm. That fits with the experience of Tyrangiel, who credited the power of the narrative and the creativity of the team of editors, producers, designers and technologists who brought the story to life online.

"What we've seen consistently is the best, most industrious stories perform best on the Web," said Tyrangiel. "In an infinite publishing platform... There's a basic differentiation when you go long or deep or the prose is really polished. It really stands out. So much of what you're reading is ephemeral."

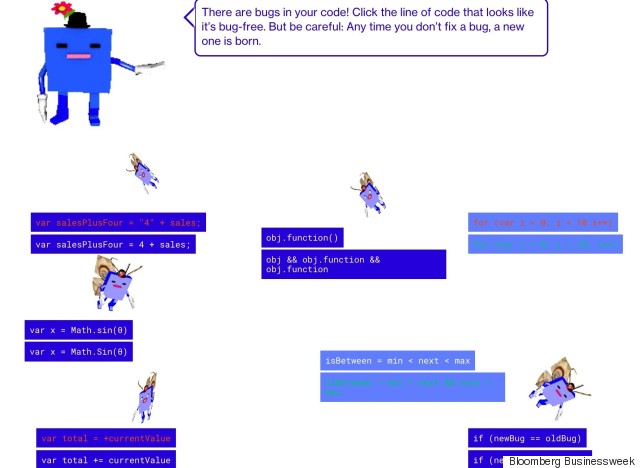

To get to that point, the editors, producers and designers tried to step outside the basic article format. They also had to decide how much to challenge readers. Early in the development process, the editors and producers considered making readers complete coding challenges to advance in the narrative. They scrapped that idea as putting up too high of a barrier.

"There was a debate about whether we leave code in the story," said Tyrangiel. "Some people see it in the text and say 'hell no, this is not for me.'" He added, "There's going to be some things that go over people's heads, and that's ok. Those flourishes, technologically, are sort of like the Russian names in 'The Brothers Karamazov.' You don't read each one, but you know that you're in Russia, and you know that the names matter. I don't know anyone that got 200 pages into that book and said 'no way, sunk costs, I'm done.'"

That metaphor is apt: if you don't understand what code is or how it works or how and why syntax looks the way it does, you really are in a foreign country, confronted by a foreign language. But if the article succeeds, the reader will find it a guide book to this world, an augmented version of a well-thumbed Frommer's guide.

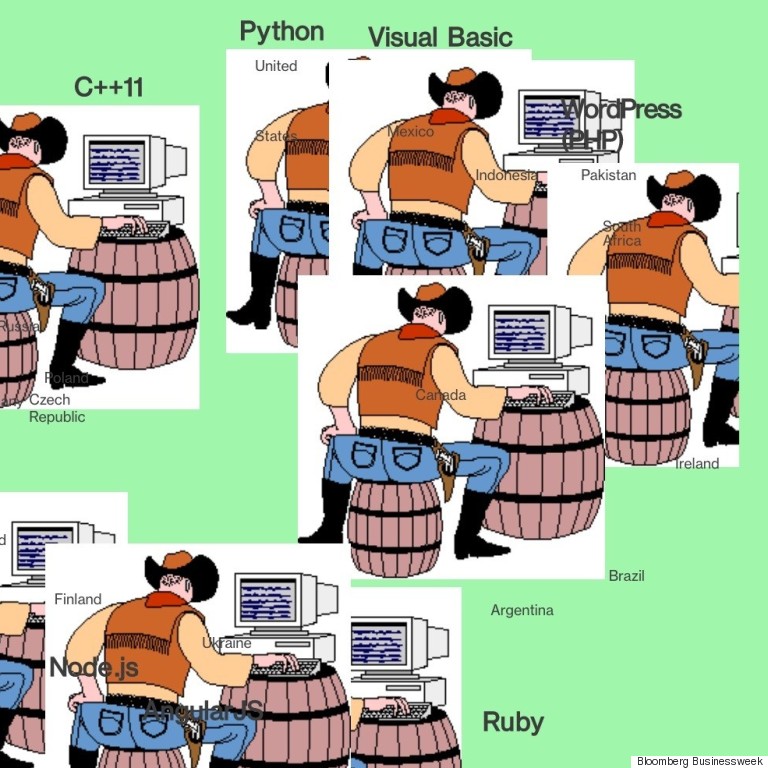

The interactive features integrated throughout include fun asides and hidden treasures, from cowboys to a button that makes the entire page fall apart.

For instance, to unlock one of the most entertaining secrets in the piece, just use your arrow keys to recreated the famous Konami cheat code from the video gaming world: left, left, right, up, up, B, A. While this Easter Egg is fun, the other interactives are meant to teach us something, just like the narrative itself.

"We wanted all the interactives to work really closely with Paul's text," said Stephanie Davidson, the designer who worked on the article. "It's not to teach you about what code is, but to help you understand what he's talking about. We pack a lot in there to keep people reading all the way to the end to get certificate."

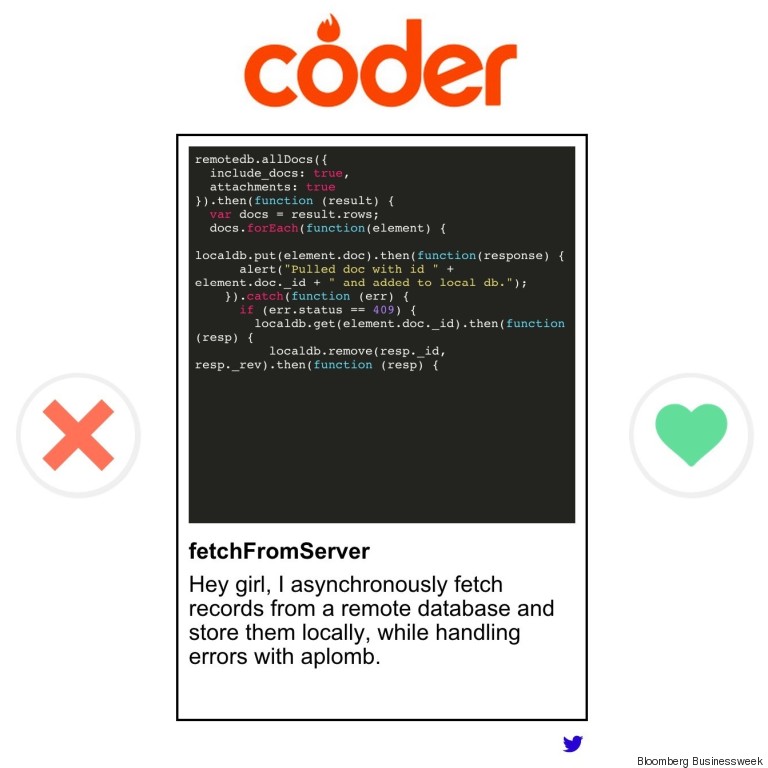

One cool Web app lets users compare two excerpts of code and decide which is sound. "It's the Tinder for code," said Topolsky. "We thought, 'what about 'hot or not' for code?' Well, now it exists."

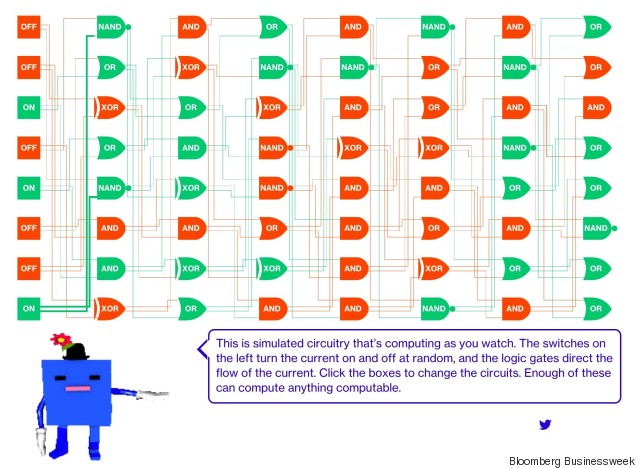

Another interactive describes a fundamental element of computing: the circuit.

"One of the reasons I called out the circuit diagram is that it's actually doing the thing Paul is talking about," said Toph Tucker, a Bloomberg Businessweek software developer who worked on the project. "Data journalism is very exciting. This is 'simulation journalism,' in that it doesn't just take data and visualize it but takes data and does something with it. The Upshot has a taken a great job with that, with the rent calculator or the World Cup draw.

The diagram also accomplishes something quietly awesome. "It's not complete, because you can't rewire it, but the fact that there's a circuit in the article makes the page quasi-Turing complete," said Tucker. "There's an almost Turing complete simulation running on a Turing complete computer." What that means, in layman's terms, is that the circuit diagram can be used to simulate a Turing machine, a theoretical device named for iconic British mathematician Alan Turing that can be used to symbolize the logic within any computing algorithm, or set of instructions.

To pull that off is almost transcendently nerdy, in a way that may also be lost on you, dear reader, but for people who live and breathe computer science, it may well prompt a good chuckle.

Inside jokes aside, it's impossible not to notice the blue cartoon character who follows you along as you read and leads you through the interactive.

"The bot was a bit risky, because everyone hates Clippy," the animated paper clip in Microsoft Word, said Davidson. "But it seemed like a good fit. With so many high-level interactive demos, it's good to have a motif to balance it out."

Variously called Paulbot, Robot or Buddy by the team, the cartoon has a snarky personality that comes out over time, particularly if you scroll quickly through the article.

"I love that the story talks back to you," said Tyrangiel. "We know that you scrolled three-quarters of the way down in a few seconds. The story is colloquial, and having a buddy along the way makes it more fun."

There's something else going on behind the scenes of the article that will be much less obvious to the casual reader than the Paulbot: the piece is steadily improving as the code and data behind it is updated from the "What Is Code" repository on Github, the social software platform.

Corrections to code and copy for the piece are being submitted as pull requests, not letters to the editor. It's a perfect metaphor for how a story made out of code is edited differently and can work differently than a static article, infographic or visualization. While calling this arrangement the future of news is a cliche, it's hard not to look at the phenomenon of people helping to fix or improve programming elements of a story made out of software as another step on that journey.

If you look at all of this from a step further away, this story about the hidden workings of software is really an interactive form of service journalism.

"This whole article is conceived with the idea of service," said Ford. "It's teaching people what I know, spreading power around and giving people the ability to understand and manage their own environments with more awareness. Computers are wonderful teaching tools. I would love to see a tutorial framework bloom inside of the Web content world."

Now, Bloomberg Businessweek is having its own "Snowfall moment," as Clinton Nguyen put it at Motherboard, referring to an award-winning 2012 interactive in which the New York Times pushed the boundaries for designing articles online.

"This is one of the most important things we will do in journalism on the Web right now, telling stories in way that's new," said Topolsky. "You don't have to just have a picture and a wall of text."

David Leonhardt, the editor of "The Upshot," the Times' data-driven journalism blog, acknowledged how the world has changed in a letter to readers this past April.

"The tools of digital journalism mean that blocks of text are not always the clearest, best way to deliver information," he wrote. "I know that some word lovers will argue that the alternatives to text “dumb down” journalism, but I disagree. When done right, photo essays, maps, charts, videos and interactive calculators can be smarter than paragraphs."

For Bloomberg Businessweek to not only acknowledge but fully embrace the Web as a medium for great storytelling is notable, particularly in a moment when more and more publishers are moving to native news apps on mobile devices.

"I like to think the spirit of play and fun in the tech world is what is so desperately needed in the media industry, as we try to talk about platforms and publishers," said Ford. "This is not about 'content.' This is about making the Web platform do something exciting and reactive, and building up libraries of code that can be reused to make later experiences."