I read David Copperfield as a student in 1970, and until recently the single detail that I remembered from it was that of Uriah Heep's handshake. Heep is a law clerk working for a kindly attorney named Wickfield, who has just taken over the very young David's care. The boy has struggled through a years' long, brilliantly described journey to free himself from the clutches of his cold, distant stepfather Edward Murdstone and Mr. Murdstone's horrid sister. David is overjoyed by his new good fortune with Mr. Wickfield. But he does have to tend with Uriah Heep: "Oh, what a clammy hand his was! as ghostly to the touch as to the sight! I rubbed mine afterwards, to warm it, and to rub his off." Later, David mentions the trail of Uriah's sweat across the page as he traces with one finger what he is reading. I could imagine the very paper disintegrating with the destructive acid contained in that finger's touch.

I just finished reading David Copperfield once again, and there is more to it--a great, almost insurmountable deal more--than Uriah Heep's perspiration. Young David has lost both parents, attended school, been abandoned and traveled alone and homeless through a vast English countryside. He has been treated sometimes badly, sometimes well by many and various people, he has entered the legal field, fallen in love more than once, gained, lost and regained many friendships, and been forced to deal with terrible people, who have had significant influence over his affairs, many times.

All the while, his adventures have been described by a fully adult David Copperfield, working alone with pen and paper on this autobiographical manuscript, telling the tale of his youth. Copperfield frequently interrupts the flow of the tale, to cogitate on what the events he has been describing from those years meant to his emotional development and his ultimate personal character. If ever there were an understanding witness to the boy David's travails and difficulties, this older man Copperfield is surely that. When we are listening to his observations, told many years after the fact, he makes those observations with an always-clear eye, contemplative feeling, and compassion.

There is a distinct difference between this memoirist's adult reflective style, and that which he employs to describe the boy David's fractious growing up. The older Copperfield is calm and reflective. The younger David (who, when not in the arms of the few who really love him, is always on the run or being challenged, beaten, rejected, fooled by someone or relieved of his few pennies) is a seriously threatened, sweet-minded naïf (although, as he grows older, he eventually becomes wiser.)

On this new reading, I was almost incapable of following David's youthful peregrinations in a calm state of mind. He is in some kind of crisis almost always, and the language is so full of movement, surprise, hurry and abrupt contemplation that even my breathing was affected by my reading. To use the old phrase, I could not put the book down, and until I started writing this piece, I could not understand what the actual writer Charles Dickens had done to make the book so electrifying to me.

But now I know.

The clue is that everything in Dickens's writing pulses with movement. All of the detail that seeps from the end of his pen shimmers. This is so even when the simplest, most pedestrian every-day object is being described. Clothing, papers piled on a desk, a woman's sleeping cap, the appearance of something as simple as the whiskers on a man's's face...nothing escapes Dickens's attention and his wish for a kind of completion and humor that the reader, trying breathlessly to keep up, can not possibly expect before reading it. All, whether good for young David or ill, moves. Everything steps back and forth, looks to the side, reflects constantly changing light and color, and beats with life. The language Dickens selects describes in phenomenal detail, throughout the novel, the character being described, the place being visited, the vista being observed, in ways in which nothing is static. Everything is excited and, in its language, dancing.

For example, after a few hundred pages, we meet a certain Mr. Spenlow, who is considering training young David to become a proctor, a kind of sub-lawyer in the court system in London. Mr. Spenlow himself is not a central character, although his daughter Dora later does have a deep effect on young David's emotions. But Dickens, in the paragraph in which he first brings Mr. Spenlow on stage, celebrates the very unusual manner and dress of this minor man, thus making him unforgettable. When I recall that Spenlow is just one of many, many characters described with such originality, I shake my head with wonder at the depth of Dickens's ability.

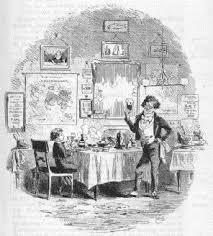

"Mr. Spenlow, in a black gown trimmed with white fur, came hurrying in, taking off his hat as he came. He was a little light-haired gentleman, with undeniable boots, and the stiffest of white cravats and shirt-collars. He was buttoned up, mighty trim and tight, and must have taken a great deal of pains with his whiskers, which were accurately curled. His gold watch-chain was so massive, that a fancy came across me, that he ought to have a sinewy golden arm, to draw it out with, like those which are put up over the goldbeaters' shops. He was got up with such care, and was so stiff, that he could hardly bend himself; being obliged, when he glanced at some papers on his desk, after sitting down in his chair, to move his whole body, from the bottom of his spine, like (the puppet character) Punch."

With this passage, my eye was going over Spenlow so quickly, the author Dickens's attention to the details of Spenlow's appearance so hurriedly provided and then moved from, left behind for the next detail and then the next...and with such ravishing color and noisy precision...that I was a couple of paragraphs further along before I realized the wondrous manner in which Spenlow had been described. I stopped and went back. I have had to calm myself, reading this novel, so that I could enjoy what I was reading while I was reading it. But on dozens of occasions, I was so driven on nonetheless to the next event by the power of Dickens's language that I had to go back, to read this or that sequence again.

I loved having to do so.

Terence Clarke is writing a new novel--The Splendid City--that has Pablo Neruda as its central character.