These days, everyone rides on planes. But have you ever ridden in a blimp?

Although we often see blimps gliding gently over cities and football stadiums, vey few people have ever flown in one. There are no regularly scheduled passenger blimp routes anywhere in the world. Blimp tickets are almost impossible to come by.

That's why I jumped at the chance to take a short demonstration ride in an advertising blimp on a promotional cross-country journey sponsored by Hendrick's Gin. I could finally answer a question I've pondered since childhood: What's it like to ride in a blimp?

Preparing

Everything about blimp-travel is unexpected, right from the start. Where do they even land so people can climb aboard in the first place? You won't find any blimps at most major international airports; too risky to have these slow-moving craft crisscrossing the flight paths of incoming jetliners. Instead, blimps generally dock at small, sparsely used local airports. (Goodyear also runs three dedicated "blimp ports" for their fleet).

In our case we travel to a little-used grassy field at the back end of the Livermore Airport (on the outskirts of the San Francisco Bay Area), where the Hendrick's staff are marshaling a handful of journalists two-by-two for brief excursions on a small promotional blimp decorated to look like a giant cucumber.

When it's our turn, there is no Homeland Security checkpoint, no X-rays -- we simply walk across the lawn to reach the blimp. We've already stepped into the past.

Boarding

The seemingly simple act of climbing aboard a small blimp's gondola is actually a comical do-si-so waltz in which the previous disembarking passengers are not allowed to get off until, one by one, the new passengers get on. This is because the lifting power of the blimp's helium is perfectly balanced with the weight of the passengers; if everyone got off first, then the blimp might start to drift away or ascend (should the winds blow the wrong way) before the next passengers got on. Fully loaded, blimps are designed to be just barely heavier than air, so embarking and disembarking is a carefully choreographed square dance designed to ensure the load is never underweight.

Did I mention helium? A few basics before we take to the air:

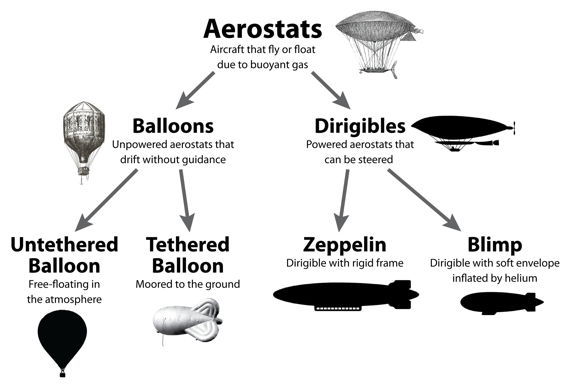

A blimp is basically a large soft bag inflated with lighter-than-air helium gas, and guided by engine-driven propellers. Zeppelins, in contrast, have rigid frames, and used to be filled with hydrogen, which is cheaper than helium -- but explosive. After several high-profile accidents in the 1930s, hydrogen-filled zeppelins stopped being made. But blimps were safe, because helium can't burn, so they remain popular to this day.

As the illustration above shows, blimps are a type of "aerostat," meaning any kind of aircraft (including balloons and zeppelins too) that floats on lighter-than-air gas.

Ascending

Our pilot, Charlie Smith, is as affable and easygoing as the blimp itself. "The experience of riding a blimp is actually more like sailing on a boat than flying in a plane," he explains as we buckle ourselves in. "We'll be floating, low and slow, not flying aerodynamically."

And with that, the ground crew lets go of the ropes (more on that later), Charlie angles the nose up, and within moments we're airborne. There's no runway, no need to accelerate, no big buildup. Just start the engines, and off you go.

The initial giddy sensation of effortless flight is tempered by the next big surprise: the noise. I had always imagined that riding in a blimp was completely silent, drifting peacefully through the sky, waving at the little people below. But no. The engines that power the propellers aren't silent at all; they're not even quiet. And because the gondola isn't pressurized, a small blimp's engine noise sounds like you're standing next to a 18-wheel truck.

Luckily, Charlie has outfitted us with headphones that not only cancel out the noise, but which allow us to communicate easily over the gondola's internal sound system.

Flying

We slowly float upward to about a thousand feet in the air and start a meandering joyride above the Livermore Valley. Peering out the rather flimsy-looking windows, I mention to Charlie that I'm a bit acrophobic. He reassures me: "Blimps really are the safest aircraft: even if the engine died and we lost power, we'd still stay floating and eventually we'd descend very slowly for a soft landing."

After a while we become accustomed to the noise from the engines, the fear drains away, and before I know it I feel perfectly at home in the sky, as if all those childhood dreams of flying had not been dreams at all, but premonitions. "Flying" peacefully in a blimp doesn't make you feel like Superman; it makes you feel like a cloud.

A jolt of terror interrupts my reverie when the nose of the blimp (and the gondola along with it) suddenly dips downwards at a precipitous angle. Were we about to crash? Charlie laughs. "Dips like that happen all the time in a small blimp -- even on calm days it will sway up and down," he explains as the gondola quickly rights itself. "It's due to swirling wind currents. But the dips are not dangerous, because the blimp is not kept aloft through aerodynamics. Although we were pointed down, we weren't going down. You can't stall or dive in a blimp. The helium always keeps us afloat."

As we watch cars stuck in traffic jams below and jetliners rocketing through the stratosphere above, the relaxing, gentle sensation of effortless blimp transport began to feel vastly preferable to either. I ask Charlie why blimps aren't used as the dreamt-of "flying cars" futurists have always predicted.

"Well, blimps are more fuel efficient than planes or cars: For this entire half-hour flight, we'll probably burn just one gallon of fuel. The support vehicles on the ground use a lot more fuel than the blimp itself!" He's interrupted by another hair-raising dip. "But that right there is the main problem: Blimps are somewhat at the mercy of the winds, unlike ground vehicles. Also, we go pretty slow, maybe 30 miles an hour. A car will almost always be faster."

The main cost of operating a commercial blimp service, he explains, would not be flying the blimps, but landing them. "As you can see, it takes just one person to fly a blimp," Charlie says, slowly steering us back toward the airport, "but it takes at least ten people to take off and land. The expense of the ground crew's salaries is the main reason you couldn't make a business out of it. If there was a way for the pilot to just safely land all by himself, that would change everything and make commuter blimp transport affordable."

Landing

Moments later we witness first-hand what he meant. As we drift lower and lower to the landing field, a small swarm of sturdy men begin chasing the blimp, leaping for the many ropes trailing from the nose. In under a minute eight men have firmly grasped the ropes, and their weight is enough to bring the blimp to a halt. The landing is so soft we barely even notice it.

Because ours was the last flight of the day, there is no waltz with the next set of passengers; instead the ground crew ties the blimp to a heavy, fixed mast to keep it from blowing away while unoccupied.

Dirigible masts don't necessarily need to be on the ground. During the heyday of zeppelins in the '20s and '30s, it was assumed that they'd become the dominant form of mass transit between big cities, so that the "flagpoles" you see atop many skyscrapers from the era -- including the Empire State Building -- were actually designed originally to be mooring masts for zeppelins and blimps. (How they expected people to get from the blimp into the building has always mystified me.)

Disembarking

Once the blimp is firmly tied to the mast, the crew brings heavy sandbags over to the gondola, and we're only allowed to disembark after our bodyweight had been sufficiently replaced by the sandbags.

And once our feet hit solid ground, we understand why blimps are compared more to boats than to airplanes: Having acquired "blimp legs" from the the mellow swaying of the blimp aloft, the ground by comparison is disorienting in its unmoving permanence. We stagger a bit at first, but as we quickly grow re-accustomed to land-based stability, we can feel the magic ebbing away.

Riding

Sadly, there is no reliable way to snag a blimp ride in the United States. Goodyear only very rarely offers rides on its famous blimps "by invitation only" to the media and dignitaries, or as a promotional exchange with major charities. A small company called Airship Ventures formerly offered sightseeing zeppelin rides for a few years but closed in 2012. Zeppelin NT in Germany (of course) is the only company worldwide with regularly scheduled (and pricey) zeppelin rides. If you're in the US, your only chance at the moment is to look for the Hendrick's cucumber blimp in the sky during the summer of 2015 and tweet a photo of it to hopefully win a promotional ticket.

(All photographs and illustrations © 2015 by Kristan Lawson.)