As a mother of three boys, I would sometimes ask them during their adolescent years, "Are you practicing to be ventriloquists? Is that why you don't open your mouths when you speak?"

Eventually, I realized that, since teenagers are often expected to stop saying what they mean, and instead say whatever the adults think they should say, most of them just shut up for about five years.

One of the first things we communicate to our young children is that it's sometimes not all right to say what they think. In fact, we teach them that it's more appropriate to tell small lies.

It's a lot for our kids to process, especially since they have a huge need to communicate and to share what they're thinking, which helps develop their speech and language.

Then we complicate it further for them by saying things like: "Don't do that." "It's not nice to say that." "You shouldn't think that." "Stop crying." "You're not hurt." "Stop worrying." "Be strong."

And at the same time we're telling them to be and do something other than what they're feeling, it's not working for us either. It's not possible to tell a lie without telling the truth at the same time, so our true intentions always reveal themselves. We'll communicate the truth through our voice, our facial expression or our body language.

That's why, whenever we're communicating with someone, it's important to watch the whole person in order to know the whole message. The secret is in caring about what others want to say and why they want to say it. Taking the time to ask, "What does that mean?" without feeling threatened by what it means.

And it's especially true with children because they've developed a coded language for disguising what they mean when they're afraid to say it. It's called kid-code.

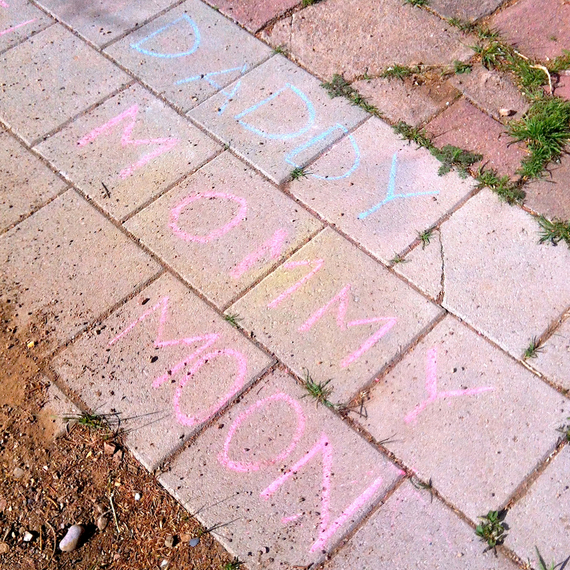

They start out expressing freely, and then we begin to censor them, so they begin turning their message around backwards.

They learn to talk in a code. And if we don't understand the code, we're likely to feel hurt and to react in ways that are not in everyone's best interest. So we need to learn to consider opposites, which is one of the keys to unraveling the code.

If a child has a cool toy, our child might say, "What a stupid toy!" which could mean, "I wish I had that toy, but I don't think my parents will get it for me." Or "I want to play with your toy, but I think you won't let me, so I'll act as if I don't want it."

Or if a child makes a good drawing, our child might say, "That's ugly!" which could mean, "That's a good drawing, and I'm afraid I can't do as well, and I don't want to look bad, so I'll pretend I know better."

What else? "Do you love me?" might mean, "Am I important to you, and will I get to always be with you?"

"Did you bring me something?" might mean, "Did you think of me while you were away, so I know I'm still important to you?"

"I hate you!" might mean, "You're disapproving of me right now, and I can't stand the feelings, and so I hate myself."

"I hate my life!" might mean, "I don't understand what's going on, and I'm afraid of what will happen next."

We all want to be understood and accepted, especially kids. It's a driving force in our communications and interactions. And understanding occurs more through empathy than through logical thinking.

When we care so much about what our kids want to say that we forget about ourselves, we're able to discover not only what they think and feel, but also why they think the way they do.

It doesn't work if we to try to simplify and make unimportant the problems of our children when what they want is to be understood.

We've all had a child come to us with an impossible situation: Someone broke her toy, we can't fix it, and the other child can't replace the original one. "See, it's hopeless!" is our child's message. If we say, "Well, it's not that important. We'll buy another toy," she'll probably say, "No! I don't want another toy!"

That's kid-code, and the true message is masked. She's right that she doesn't want the toy. What she wants is understanding that it was important to her. If she feels heard and understood, she might say, "Oh, it's all right. I don't need that toy anymore."

Children want to know why about everything, and that's always the question for us to answer. If they don't understand why something is so, and they can't word their question effectively, they might conduct little experiments. "Here, Mom and Dad, look what I'm doing! What's your response now?" which could mean, "Will you still love me if I go this far? Will you accept me no matter what?" If we miss the kid-code, life can become a chaotic roller coaster ride of trying to control what we believe is inappropriate behavior.

If we can't figure out the code, we may just have to sit down and ask our kids what they really mean. "How do you feel about that?" works better than "What are you trying to tell me?"

Our children might not even know what they really mean or what they're trying to say. So guiding them, by asking questions, can help us discover their concerns and anxieties, and what they're trying to work out in their minds. Not as an interrogation, but rather, friendly and loving questions, for the purpose of helping our children express themselves honestly, without fear. Then they won't feel the need to come at the truth from the opposite side.

We parents have to be geniuses... because our children are!

This article is posted on Grace's blog at gracederond.com. You can also follow her on Facebook and Twitter.