Now we see why the ancient Mayans built their cities inland from the coasts.

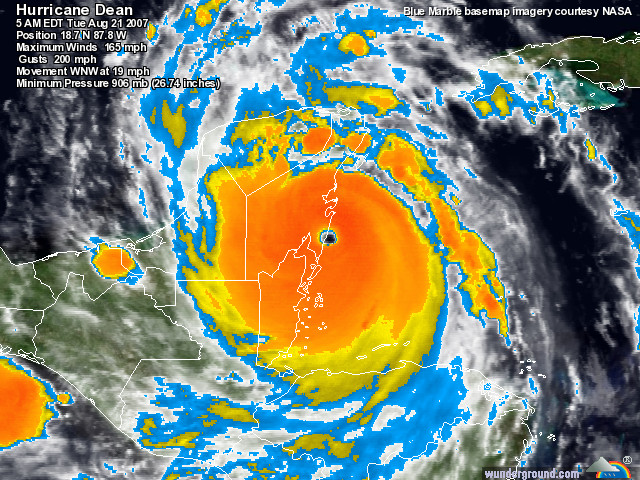

Early this morning, Hurricane Dean slammed the Yucatan as a still-intensifying Category 5 storm with sustained winds upwards of 165 miles per hour. Dean required some troubling readjustments of our hurricane records, and as a result, we may hear some serious chatter today about the relationship between these intense storms and global warming.

For that reason, the purpose of this post is to lay out what we can and can't reliably say about Hurricane Dean. The upshot is this: We have to be careful what we claim and how we claim it, but even so, Dean fits into a worrisome pattern.

Here are the key records that Dean either broke or otherwise affects:

1. With a minimum central pressure of 906 millibars, Dean was the ninth most intense hurricane ever observed in the Atlantic basin (for comparison Hurricane Katrina's minimum pressure was 902 millibars).

2. That 906 millibar pressure reading was at landfall, making Dean the third most intense landfalling hurricane known in the Atlantic region and the first Category 5 storm at landfall since 1992's Hurricane Andrew.

3. When measured by minimum pressure, six of the ten most intense Atlantic hurricanes--Wilma, Rita, Katrina, Mitch, Dean, and Ivan--have occurred in the past ten years.

We can't blame any one hurricane event on global warming directly. Nevertheless, the information above is certainly consistent with the idea advanced by some scientists that global warming is causing an intensification of the average hurricane. We're apparently seeing the strongest hurricanes recur in the Atlantic with a higher frequency than before -- or at least, than we've ever been able to measure before.

Measuring systems weren't as good in earlier eras, you see -- a fact that makes our records somewhat impeachable. A "record" is only what's recorded, after all. And so skeptics will inevitably quibble with our imperfect data and challenge it. There might well have been a storm much stronger than Dean 200 years ago -- we just don't know.

Nevertheless, if you look at the data we have, Dean fits into a very troubling pattern and context. Moreover, the present data, with all their admitted imperfections, aren't all we have to go on. There's also the theoretical expectation that hurricanes ought to intensify, for basic thermodynamic reasons, as global warming adds more heat to the oceans. Add together this theoretical expectation with the new records today and, well, anyone would be justified in feeling pretty worried by Hurricane Dean.

Dean was also the strongest hurricane anywhere in the world so far this year -- and by far the strongest at landfall. We can only hope that somehow, the damage is lighter than expected as the storm tears across the Yucatan today and then prepares to cross the Bay of Campeche and make a second expected landfall in mainland Mexico.

For a further and more detailed discussion of Dean in its Atlantic and global context, see my "Storm Pundit" post at The Daily Green, available here.