This year, my son with autism became a member of his school's track team. Barrett wouldn't be able to be on the team if it weren't for the village of people who support him. A fellow student (who's not on the track team) attended practices with Barrett and ran with him in the meets. The student who helped is an autism peer at his middle school. He's one of many. Forty students volunteer in Barrett's class, which has been dubbed by everyone as, "the Awesome Class."

To be a peer volunteer, you have to have certain characteristics. For starters, you must have a lot of patience, show respect (to teachers and students) and be flexible. All peers in the program had to apply, provide two staff recommendations and write an essay explaining why they want to help in the classroom. After that process, the potential peers must participate in what I'd call a mini boot camp. They have to work in the classroom for a week (after signing a confidentiality agreement), take an autism tutorial online and meet with the teacher (Mrs. Corcoran). At that meeting, the teacher and student discuss whether or not it's a good fit.

For the sixth graders, their first tour of duty is a nine-week session. Their primary responsibility is to work with the students in a group setting, so they can get to know them and gain a more comprehensive understanding of autism. It also gives the teachers an opportunity to emulate and determine if they can handle a semester-long assignment in seventh grade.

During the seventh grade semester, peers are given a one-on-one assignment with a student so they can develop a connection. Each day they attend an elective class with their assigned student, usually art or PE. They help the students by breaking down the assigned tasks into easier to understand steps. Often, a parapro helps them determine the steps. Peers also help the student stay focused in the inclusive environment -- they're the wing-man in a world that is bigger world than the self-contained classroom. If it were not for the peers, Barrett and his classmates wouldn't be able to attend electives every day.

Those peers who return in help in eighth grade usually stay for the full year. At this point, they're veterans and as such, take on more responsibility. They are assigned 15-minute cycles to rotate with different students and/or different tasks. The tasks are more academic-focused and have specific teaching goals. Mrs. Corcoran has discovered that often her students learn faster when working with a peer.

The peers work in the classroom every day. The program takes the place of one of their electives and they receive a grade. Those looking for an easy grade need not apply. These kids really work -- trust me, I know. I've seen it in action and sometimes it's not for the faint of heart. They really impress me, because when I was in middle school, I also volunteered in a special needs classroom. I lasted exactly one hour. I'm not exaggerating. In addition to the grunt work, the students also have a curriculum filled with vocabulary words, written assignments and lots of reading. For each book assigned, the peers have to write a summary. At the end of each semester there's a final exam and they must write another essay describing what they've learned from working with children on the spectrum.

Still, there's a great demand to be in the classroom. Mrs. Corcoran routinely has to turn students away. I was curious as to what kind of person feels the pull to work in special needs classroom at 12 or 13 years old. The only common trait I can discern is a caring heart and call to serve. There's someone from every "clique" in school, which I think is amazing. Imagine the Breakfast Club, but they're all volunteering of their own free will.

Mrs. Corcoran told me that at least three of the peers want to be special education teachers, another four have expressed interest in occupational, speech or physical therapy. And another student wants to be pediatric neurologist, focusing on autism. Would these career aspirations come to fruition without the peer program? Who knows?

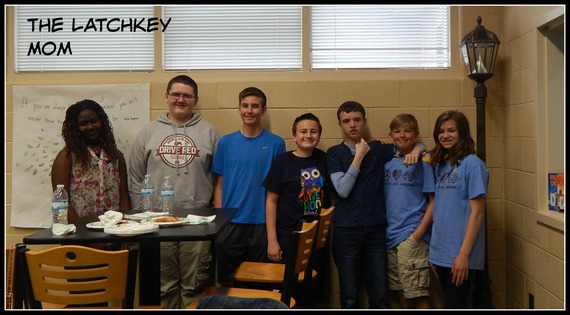

What struck me, as I had lunch with some of the peers and my son, was the effect their presence had on Barrett. Barrett has matured quite a bit in the last year, but still, I was seeing altogether different boy during our lunch. He did not get out of his seat once, not even to jump up and down (something he often does when an environment get too loud). I'd arrived with three boxes of pizza, which were in his sight and within his reach. He did not attempt to get up and score another slice. Not once. He did look around and stare at the boxes, but he refrained from any attempt to swipe a slice. One of the boys noticed this and asked Barret what he wanted. Barrett replied, "pizza." Then Barrett looked to me. Well, I had an audience, so I had to do the right thing, which was to require Barrett to ask with a full sentence. When I do this at home, especially when he distracted by his love and desire for pizza, in can be a bit of an ordeal. Usually I have to prompt him repeatedly, and model what he needs to say -- verbatim. Sometimes he gets impatient with me, ignores me and gets his pizza, laughing as he does.

So I put on my autism mom hat and said, "Barrett, you need to ask me properly." Then I felt a twang in my belly, as I braced myself for his reaction. I was fully expecting to me embarrassed.

He looked me in the eye and said, "Mommy, can I have another piece of pizza, please?"

You could have knocked me over with a feather.

At another point, Barrett was drumming on the table. This drives me crazy. Before I could reprimand him, a peer beat me to it. "Barrett, we don't do that at the lunch table."

Would he believe that he stopped? Right then I was blown away. It dawned on me that Barrett cared about what these kids thought of him. Barrett has never cared about what people think of his behavior. He wanted to fit in, he wanted to one of the gang. And he was.

Later, I observed in the classroom and got to witness a "shift change." For each new period, a new crew of kids takes over. I thought it was all a bit chaotic, because at one point there were a lot of people in one room, plus two service dogs. I'm not on the spectrum, but could feel my anxiety level rising -- just a tad. But, it was seamless. Each new peer buddy tagged the old one out, checked their student's schedule and they were off. Barrett and some nice young lady, who helped him change his shoes for P.E., left together and he didn't even look back to see if I was watching or even still there.

I asked the group if they were ever bullied for being peer buddies by their mainstream classmates. They all looked appalled by the question and unanimously and strongly answered that they never were. They said everybody in the school thinks it's cool -- and many of their friends also want to be to peer buddies.

Times have changed and I'm so grateful. Not only do these kids help Barrett and his friends, but they are champions for their cause. They set an extraordinary example for a whole student body and they make their teachers and administration proud. They are actively molding the future for our children through their actions, and with their kindness and generosity. Seriously, I think every child, regardless of whether they are special needs or not, should have buddies in their corner like my son does. I'm so grateful and full of love and hope for the future.