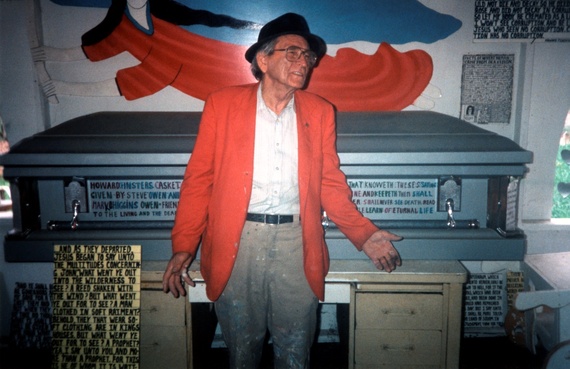

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of one of the most charismatic, productive, and celebrated visionary folk (aka self-taught, outsider, or vernacular) artists of the last quarter of the 20th century. I refer to Howard Finster (1916-2001) - someone who with varying degrees of sincerity was often called the "Backwoods William Blake" and the "Southern Andy Warhol." A garrulous Baptist preacher, inveterate tinkerer, and tricksterish showman living in the highlands area of northwest Georgia, Finster in the early 1960s, and then most dramatically in 1976, started to receive interplanetary visions that prompted him to construct a roadside bible park and junk assemblage that came to be called Paradise Garden. Making almost 50,000 "bad and nasty" paintings and other artworks, Finster's sleepless busyness and raw try-anything creativity produced many extraordinarily strange works during the 1970s and 80s that brought him national and international renown. Indeed, Finster's funky visionary work in the 70s and 80s resonated with the Pop and Neo-Expressionist turn away from Abstract Expressionism toward a figurative subject matter which for Finster involved clotted biblical imagery, cartoonish flying saucers and sleek Cheetahs, rustic sayings, and all manner of popular cultural icons like Coca Cola, Mona Lisa, Mickey Mouse, Elvis Presley, and Marilyn Monroe.

In the dark apocalyptic times after Finster's death a month after 9/11, Finster was considered by his many fans and artworld insiders (see the 2002 Raw Vision Outsider Sourcebook and Roberta Smith's obituary in the New York Times, October 23, 2001) as one of the remarkable outsider artists of the 20th century. Certainly also, it seemed, he was someone who deserved a prominent place in the history of 20th century American art. Even better was the sense that his art (the early works if not the myriad later cutout multiples) would significantly appreciate like the work of other outsider giants such as Martin Ramirez, Henry Darger, and Bill Traylor. So in Finster's centennial year, the question is simply: what happened? Allowing for a few important exceptions, why does it seem that in mainstream art salons there is almost a studied effort to ignore Finster, to belittle his artistic significance, and to suggest that it was all a temporary infatuation with his eccentric personality and homespun celebrity rather than any substantive appreciation of the quality and enduring significance of his artwork.

Having just written an interpretive study of the distinctively intertwined nature of Finster's art and religion (Envisioning Howard Finster: The Religion and Art of a Stranger from Another World, 2015), I'm admittedly biased with regard to these matters. However I do not think that that I am totally misreading the signs of the times with respect to the relative eclipse of critical interest in Finster. The fact is that outsider art gatekeepers no longer spontaneously invoke Finster as an outsider giant alongside the pantheon of Ramirez, Darger, and Traylor. I do not mean to cast doubt on the greatness of this extraordinary triumvirate, but what explains the diminishment of Finster? What is truly curious about the case of Howard Finster is the rather dramatic shift in opinion and, even more peculiar given his cultural impact, the general lack of serious interest, analysis, and interpretation of his life and body of work. In the words of the new folk art curator at Atlanta's High Museum Katherine Jentleson, the time has come for a "reappraisal" of Howard Finster (Art Papers July-August 2015).

There are numerous issues to consider not the least of which is a kind of "nostalgia for authenticity" and an escapist tendency to evaluate and promote outsider artists in relation to the quaintly exotic and colorfully "primitive" quality of their biographies. But what I want to emphasize is an important factor that all too often is avoided within the typical and largely secular narrative of modern, contemporary, and still largely Western history of art. I refer to Finster's in-your-face evangelical religiosity as a Southern Baptist and the fact that he always said he was making "sacred art" for the End Time. One way to frame this issue is to consider the perspective of the astute New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl who, when first exposed to Finster in the 1980s, was impressed and overwhelmed by the incredibly creative "irruptive singularity" of the art. However Schjeldahl tells us that he ultimately became sick to his stomach since the more he saw of Finster's sacred art, the more he realized that it was a religiously dogmatic "prison house" of the mind. As another critic put it more crudely, Finster must finally be seen as one of those disturbing Southern "religious nutters" who cannot, and decidedly should not, be taken seriously (quoting Terry Castle: London Review of Books July 28, 2011).

Let me only remark as a scholar of comparative religion that the time has come for modern/contemporary art historians to attend more knowledgeably and sympathetically to the complex history and cultural significance of religion/s (in all their glorious and awful manifestations) in relation to the nature, practice, and meaning of art. Moreover with regard to Finster it is crucial that his "visionary" experience not be dismissed too quickly as just a con-game or some kind of hallucinatory psychosis. Paying attention to these cultural and experiential issues of religiosity and art seems obvious and necessary when considering non-Western and pre-modern Western art history, but ever since the Enlightenment era and the imperial dominance of Western ways of knowing, the reigning Eurocentric paradigm has dictated an overly secularist-naturalistic, rational, and formalist approach to art. The apotheosis of these developments in many ways comes with the rise of hyper-conceptualist approaches to the production, meaning, and critical reception of art wedded to a politically correct artspeak that is predominantly political, ethnic-racial, sexual, and socio-economic in nature.

Something important seems to be missing from perspectives that ignore, and often reductionistically trivialize, the role of religion and fail to see the deep emotional and cultural linkage of aesthetic and religious practice and experience. Finster in this regard becomes particularly interesting in that he intensely embodied and lived out the interrelationship of art, religion, and craft. For Finster his religion gave passion and meaning to his art but at the same time it was his visionary experience and resulting art that significantly expanded the meaning and ethics of his religion. The gospel truth is that while Finster was a southern evangelical he was not a dogmatic fundamentalist in terms of a rigidly literalist understanding of the Bible. Finster was actually a self-proclaimed Free Will Baptist whose overriding principle was always that he liked "to feel free."

In many ways, Finster was a visionary evangelical in the expansive Moravian evangelical, symbolic, and visual sense of the great maverick 18th century visionary artist, romantic engraver, and prophetic poet William Blake. The key issue, then, with respect to Finster, as well as for many other passionate image makers often called visionaries, is that they represent important case studies in the intrinsically entangled nature of religion and art - thinking primarily and experientially of the religiosity and "spirituality" behind the religions and the artistic creativity and skill behind the different schooled arts. Here I can do no more than telegraphically raise these issues and suggest that as both Howard Finster and William Blake knew so well: "the man who never in his mind and thoughts travel'd to heaven is no artist" (William Blake, Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790-1793).