A lot of information can go into what ultimately becomes the objects on view at an exhibition. Think about the way a good journalist has to be a quick study to turn out a good story; they can't afford to invest the time of a scholar, but they had better have a solid mastery of language to give convincing shape to the information they have mastered. Artists assume a broader license. They aren't assigned a specific task, they can do as they like. If that sounds like an easier mandate, don't kid yourself. The finished product needs to engage us, but the good stuff offers multiple threads leading back to some sort of Big Bang point of origination. If that little metaphor for the creative process is decidedly cosmological, there is no shortage of art that reflects it in just that way. Andrew Schoultz throws this metaphor hard and down the middle with his assaultive explosions, tornados -- anything that intrudes transcendent energy into a world that by choice would remain placid.

The formal devices of the circle, the spiral, the vortex are perhaps history's most reliable symbols of the spiritual. But take a look at how the translucent, emanating patterns of Michael Knutson contrasted with Schoultz's hyper-aggression. If Knutson were a physicist he would be talking about the old steady state theory. However this work is not about illustrating physical laws, it's about getting the most visual complexity from the simplest possible means. The geometric forms sculpturally constructed by Garland Fielder appear to be quite simple at first, but that is deceptive, perhaps even a ploy. The artist contains a complex system of linear structures within easily grasped forms. Once your eye is drawn in you can bounce around for a good long time trying to unravel the internal logic.

Simplicity is also certainly central to Raimonds Staprans' compositions, which are still lifes set in uncluttered domestic environments, at least on the face of it. The lines that divide objects, planes and shadows contain the energy here, reading like some metaphysical force underlying the whole thing, just bursting to get out. In Patrick Merrill's images some force has been released to occupy every square inch of the picture plane. The baroque drama of his "Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse" moves from the central figures and is shared by the surrounding space, crammed as it is with the panicked mass of the dead and the dying. Such traditionally symbolic and literary figures are co-opted for Merrill's brand of expressionism. If the moral tone is overwrought, the conviction is acutely felt and conveyed.

Whether an artist bombards us with visual data or carefully controls it is a quantitative matter that is hardly crucial to what we draw aesthetically from their work. But the density and conviction of visual information, both referenced and invented, and the point around which that information is organized is crucial indeed.

- Bill Lasarow

Patrick Merrill, "Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Death)," 2002, woodcut, 72 x 36".

CSU Fullerton Begovich Gallery, Fullerton, California

College of the Canyons Art Gallery, Santa Clarita, California

Patrick Merrill left a rich legacy that resonates beyond his 40 year career as a master printmaker, mixed media artist, and gallery director. The two concurrent solo exhibitions of his art, planned over a year ago - along with a single etching included in the 30th Anniversary exhibition of the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art - are achievements he yearned to witness. But life had other plans, and Merrill succumbed to cancer on August 31st.

- Roberta Carasso

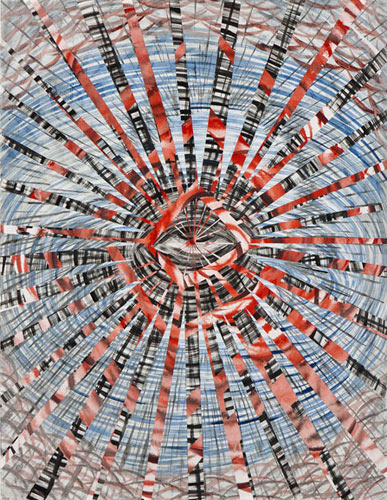

Andrew Schoultz, "Eye (Red, White, Blue), 2009, collage and monotype, 44 3/4 x 36", at Marx & Zavattero.

Continuing through October 23, 2010

Marx & Zavattero, San Francisco, California

San Francisco artist Andrew Schoultz's newest work comes at you like an explosion. It's big, bold, and colorful. It's also serious, playful, and chaotic. The show features collage and acrylic paintings, monotypes, and large-scale sculpture. Throughout, Schoultz utilizes graphic/illustrative imagery regularly featured in past work as well as his exquisitely detailed line work. In every piece there is more than a lot going on. They work on numerous levels, foremost hovering between representation and abstraction. They are a brightly twisted playground for the eye and the mind, a trip down the rabbit hole with serious social commentary.

- Cherie Louise Turner

Michael Knutson, "Tripolar Colis VI (Grays)," 2010, oil on canvas, 60 x 60".

Continuing through October 30, 2010

Blackfish Gallery, Portland, Oregon

Known for creating patterns of spiraling geometric shapes, Michael Knutson presents two exhibitions placed fourteen years apart. The earlier works are from 1996, made after the artist saw the Mondrian retrospective at MOMA. Titled "Cubic Knots," all the canvases are octagonal and painted in the De Stijl palette of the primaries plus black and white. Knutson takes formal cues from Pennsylvanian Dutch hex signs, but the patterns are more random. Each piece contains eight interlocking cubes, which play with the eye and suggest a transparency that doesn't really exist.

Nonetheless "Cubic Knots" rocks steady and is easily read next to the companion exhibition of all new work called "Transient Fields." Here Knutson uses the shape of a star, creating several layers of lattices in any given canvas. Some of these paintings are multicolored, some are monochromatic. Two of the canvases rely completely on Payne's Gray. The complexity carried out with such a limited color scheme boggles the mind. The push of the paint is all wedged in by hand, bestowing a thick, mosaic-like character. That heaviness of the material contradicts the flight of the imagery and the buoyant optimism of Knutson's palette.

- Eva Lake

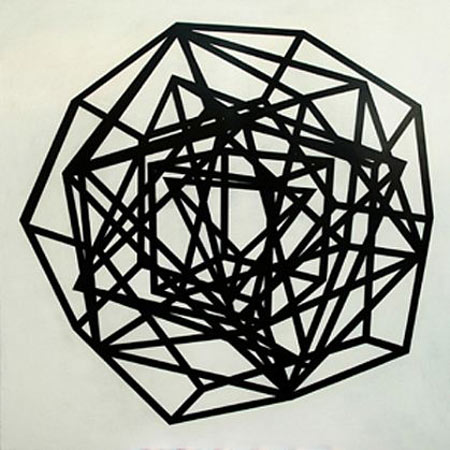

Garland Fielder, "A Theory of Everything (Version II)," 2009, at Holly Johnson Gallery.

Continuing through December 18, 2010

Holly Johnson Gallery, Dallas, Texas

The contorted and impossible geometries of Garland Fielder's painting and sculpture seem more about Gestalt psychology than Minimalism, even though he claims greater influences by the latter. What sets him apart from Minimalism, both thing and philosophical practice, is the singularity of each of his objects. Veering far from the one-thing-after-another serial repetition so central to Minimalism, no two are alike in this exhibition.

"Untitled (black contortion 05)" and "Untitled (black contortion 06)" are white cubic geometries on black matte backgrounds. Meticulously rendered, the geometries are almost feasible in reality, but ultimately not. Think here of the Necker Cube or Rubin Goblet, two very well known drawings within Gestalt psychology prized for their illumination of the ambiguities inherent to perception. A shiny black steel and a painted white polygon, "Untitled (Steel Octahedron)" and "White Cube" do not so much sit on the floor as seem embedded in it. Where each object hits the floor edges and corners go missing. Unconcerned with the core philosophy of Minimalism, the intention of which was to bring a hammer down on the old humanist conventions of truth and beauty, Fielder's pieces are more than anything else delectable formal objects.

- Charissa Terranova

Raimonds Staprans, "A Somewhat Patriotic Still Life," 2005-10, oil on canvas, 44 x 50".

Continuing through October 23, 2010

Peter Mendenhall Gallery, Los Angeles, California

The recent work of Raimonds Staprans continues his exploration of quotidian architecture. He abstracts those forms with explosive color choices. "Dark Still Life with Two Glasses" meditates on Staprans' style of delineating strict order in compositions and creating multiple spaces on the canvas with thick lines. Two glasses positioned at the far left end of the canvas glisten with a remarkable light despite the thick black line hovering above. The artist plays with the conventions of still life in presenting one glass as half full with water, while the other is empty.

Perhaps a meditation on his long career as an artist, or simply a means to establish a contrast of light in the composition, the gesture seems a fitting message. While his subjects are still lifes and landscapes, Staprans has the ability to infuse human qualities into otherwise inanimate objects. "A Somewhat Patriotic Still Life" depicts an empty glass jug and rectangular metal can with a nozzle. Once again grouped together at the far left end of the canvas, the bright light and concrete suggest the objects may be outside on a sidewalk. There is a distinctly somber tone in that the objects are vessels which contain nothing. Staprans is able to evoke a great sadness in his objects, which express a longing for and a rumination of the past, despite the beautiful light which embraces them.

- A. Moret