Today is the birthday of my twenty-third book! I haven't arranged a book launch since 2012 and as an introvert, I'm really not much of a party girl. But I've decided that the publication of this particular book is worth celebrating. It took me over a decade to finish The Door at the Crossroads--sequel to my time-travel novel A Wish After Midnight--and I'm proud of it, though it isn't the story I originally set out to tell back in 2003. Still, I finally reunited my Black teen protagonists after stranding them in separate centuries on the eve of 9/11. And I've learned to be kind to myself when it comes to my writing because let's face it--the publishing world can be brutal.

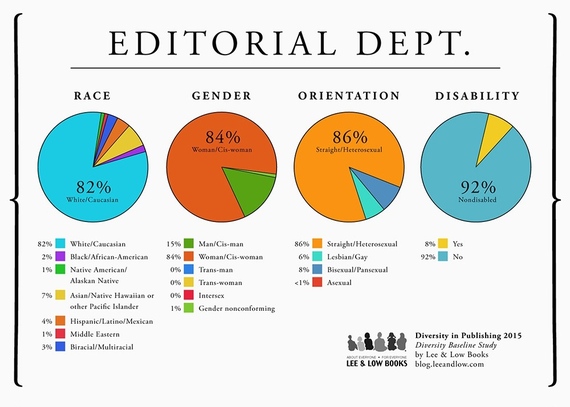

I have three traditionally published books for young readers (Bird, A Wish After Midnight, Ship of Souls) and a fourth will come out this fall (Melena's Jubilee), but the rest of my books are self-published. I didn't plan to be an indie author--who would? We're regularly scorned. But after facing a decade of rejection in an industry dominated by white women, I realized that self-publishing was the only way I could get my books into the hands of the kids I serve. And as I explained in a recent article for Publishers Weekly, I have no regrets. Three of my indie titles have been included in Bank Street's "Best Children's Books of the Year," and one (A Wave Came Through Our Window) was starred for outstanding merit.

What does it mean when stories about kids of color are rejected over and over by some white women but then declared "outstanding" by others? After spending years railing against racism in the kid lit community, I've decided the answer to that question really doesn't matter (though at least one editor has a theory). I have a new mantra these days, which I owe to African American historian John Henrik Clarke who--long before the era of Black Lives Matter--understood that "white people think when you love yourself, you hate them" (All lives matter!) These days when I think about discrimination in children's publishing, I take a deep breath and repeat Clarke's words: "When I love myself, they become irrelevant to me."

As a Black feminist I have come to understand that self-publishing is, for me, an act of radical self-care--and self-love. Most people think of self-publishing as an act of vanity, but when you are Black in an industry that is overwhelmingly white, a different dynamic is at play. As John K. Young explains in his book Black Writers, White Publishers (2006):

...what sets the white publisher-black author relationship apart is the underlying social structure that transforms the usual unequal relationship into an extension of a much deeper cultural dynamic. The predominantly white publishing industry reflects and often reinforces the racial divide that has always defined American society.

Last month I was invited to speak at Harvard for the second time. Prof. Robin Bernstein assigned A Wish After Midnight in her course, "The Child in African America," and so I met with her students to discuss the book and then gave an informal presentation at the Women's Center. My talk was titled "Inclusivity and Indie Authors: the Case for Community-Based Publishing," and it was the first time I spoke publicly about the relationship between self-publishing and self-love. I told those in attendance that a blue-haired, brown-skinned 9th grader in Brooklyn recently asked me how I persevered in the face of so much rejection. I usually say that I'm "doing it for the kids," making sure they have the "mirror books" I never had as a child. But upon further reflection, I realize that the example of other Black feminists is also what keeps me going.

When I wrote "Something Like an Open Letter to the Children's Publishing Industry" back in 2009, I drew inspiration from June Jordan's 1986 essay, "The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America: Something Like a Sonnet for Phillis Wheatley." Jordan's essay helped me understand the response of an editor who declared The Door at the Crossroads "didactic." Another editor (and self-proclaimed "diversity advocate") concluded that A Wish After Midnight, with its Afro-Panamanian and Rastafarian teen protagonists traveling to a free Black community in the city of Brooklyn during the Civil War-era, was "unoriginal." Such assessments of my work would not surprise the Black feminists who founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press in 1980, and they wouldn't surprise June Jordan. Twenty years earlier she wrote,

...the difficult miracle of Black poetry in America, is that we have been rejected and we are frequently dismissed as "political" or "topical" or "sloganeering" and "crude" and "insignificant" because...we have persisted for freedom. We will write against South Africa and we will seldom pen a poem about wild geese flying over Prague, or grizzlies at the rain barrel under the dwarf willow trees. We will write, published or not, however we may...of the terror and the hungering and the quandaries of our African lives on this North American soil. And as long as we study white literature, as long as we assimilate the English language and its implicit English values, as long as we allude and defer to gods we "neither sought nor knew," as long as we...remain the children of slavery, as long as we do not come of age and attempt, then to speak the truth of our difficult maturity in an alien place, then we will be beloved, and sheltered, and published.

But not otherwise. And yet we persist...This is the difficult miracle of Black poetry in America: that we persist, published or not, and loved or unloved: we persist.

For me, self-publishing is a radical act of self-care because it redirects my energy away from a toxic engagement with those who are oblivious to the "urgencies" of my community (I am indebted to Robin Bernstein for this definition of obliviousness: "not merely an absence of knowledge, but an active state of repelling knowledge"). Self-publishing stops me from knocking on a door that will never open--or only open grudgingly.

Telling my own stories in my own way is also, for me, the ultimate act of self-love because it is an act of resistance. It is a rejection of the implicit messages editors send along with their "Thanks, but no thanks": you're not worthy, you're not one of us, you have nothing meaningful or important to say.

And so holding a party for my twenty-third book is a way of celebrating the fact that I didn't give up. I didn't internalize the rejection and surrender my right to write. The Door at the Crossroads may not be perfect, but it deserves to exist in the world. It can serve as a mirror for so many Black teens who never get to see themselves in the pages of a fantasy novel. My hope is that my act of Black feminist resistance will inspire a new generation of writers just as Audre Lorde, and June Jordan, and Octavia Butler inspired me.