"Paul wrote relentlessly, fueled by purpose.... He started with midnight bursts when he was still a neurosurgery chief resident... drafted paragraphs in his oncologist's waiting room... took phone calls from his editor while chemotherapy dripped into his veins....

"When his fingertips developed painful fissures because of his chemotherapy, we found seamless silver-lined gloves that allowed the use of a trackpad and keyboard. Strategies for retaining the mental focus needed to write, despite the punishing fatigue of progressive cancer, were the focus of his palliative-care appointments. He was determined to keep writing."

We are so grateful that Dr. Paul Kalanithi kept writing. And we are grateful for the Epilogue to his memoir - When Breath Becomes Air - in which his wife, Lucy, provides us with the details of his determination and commitment.

When the future begins to flatline

Lucy Kalanithi, an internal medicine physician, sensitively tracked her husband's every symptom; she helped him manage - with grace and accomplishment - every aspect of arduous, depleting treatment. She encouraged and comforted him as he endured efforts to halt further metastasis; as he endured the side-effects of chemotherapies that increasingly challenged the organs, tissues, nerves, and muscles that were already under siege by cancer.

This intimate consultancy and attention, she tells us, was the most important doctoring role of her life. For the reader, her support of her husband's terminal ambitions, made it possible for him to "forge a new future" - however truncated.

In the memoir, we learn of the demands and sacrifices involved in becoming a neurosurgical chief resident; we are allowed to understand the impact of a diagnosis, at the age of thirty-six, that totally negated the future that Paul Kalanithi had put into probability by so much study, diligence, devotion and skill; we learn about grief, acceptance, adjustment, and still more acceptance.

And, most significantly, we learn how to think about our own futures, our own trajectories, our own aspirations - imagining a time when there will be complications in our own respirations.

A neurosurgeon's techniques, and talents

Prior to learning of Paul Kalanithi's end-of-life lessons, we learn about his life - and his decision to try to save lives.

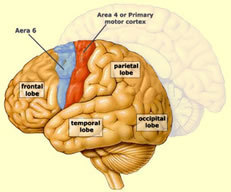

Unpretentiously, he acquaints us with what plays havoc with the brain and the delicate neurosurgeries he performed to alleviate, if not remove, the afflictions: emergency craniotomies, glioblastoma excisions, suboccipital craniectomies for brain-stem malformations, giant aneurysms, intracerebral arterial bypasses, arteriovenous malformations, temporal lobectomies, interhemispherics done parietal transcortical ....

We are given an intro to brain anatomy: the primary motor cortex, the hippocampus, the hypothalamus, the subthalamic nucleus, ....

The mind's eye is allowed to peek into the operating room

•to note that "the skin slips open like a curtain, the skull flap is on the tray before the bone dust settles...."

•to observe the "ball-tip electrode inserted to deliver electrical current to stun a small area of the cortex while the patient (awake) performs various verbal tasks..." so that "the brain and the tumor can be mapped, to determine what can be resected safely."

•to register the scalpel as it "incised the skin just above the ear... with the electrocautery, I deepened the incision to the bone, then elevated the skin flap with hooks.... I took the drill and made three holes in the skull. The attending squirted water to keep the drill cool as I worked. Switching to the craniotome, a sideways-cutting drill bit, I connected the holes, freeing up a large piece of bone. With a crack, I pried it off.... I tacked back the dura with small stitches to keep it out of the way of the main surgery...."

Reflexively, protectively, the skin above and behind my ears tightened; my forehead raises and retreats at the thought of .... Fervently, I hope I am spared such cranial measures. My palpable mental and physical queasiness made medical school inconceivable, even as the heroics of TV doctors - Ben Casey, James Kildare, and especially Gregory House - were of some fascination.

However, for anyone thinking about applying to medical school, I recommend the memoir's descriptions of anatomy lab cadaver dissections (pages 44 - 50).

For those who believe that "life" begins at conception, the description of twin preemies should prompt re-thinking, for at twenty-three weeks the twins are shy of "the cusp of viability" - visibly and biologically so. (pages 55 - 61)

Life examined

Each of us has our own particular "meaning of life" computation, which may be recalibrated from time to time - and is most certainly refigured when there's an unfavorable medical diagnosis: Is intubation and perpetual equipment-aided breathing enough? Is unconscious metabolism enough?

For each of us, there is a unique continuum - a downward spiral - descending from life-altering, to life-shattering, to life-threatening, to life-ending. Somewhere along that descent, we can hope for life-clarifying thoughts, and actions.

Who's there to help clarify? Paul Kalanithi was, and, through his memoir, he still is: "While all doctors treat diseases, neurosurgeons work in the crucible of identity: every operation on the brain is, by necessity, a manipulation of the substance of our selves.... the question is not simply whether to live or die, but what kind of life is worth living."

Paul Kalanithi tried to help his patients and their loved ones focus on the possibilities and potentials they'd hope to preserve, or salvage. "We meet patients at inflected moments, the most authentic moments, when life and identity are under threat. Our duties include learning what makes (made) that particular patient's life worth living. We work to save those things, if possible - or, if not, allow for a peaceful death."

Potentials, possibilities, examined - a different DNR

When Breath Becomes Air spares us heavy doses of metaphysical ponderings - it grounds "meaning of life" musings into something akin to arithmetic equations, risk-reward calculations: tradeoffs. More aggressive treatments, and more toxicity? More tradeoffs.

Yes, a Do Not Resuscitate may be a good move. But prior to coding, we might try to work on another DNR - a Do Not Regret mindset.

What would we risk, or what would we have a loved one risk, to preserve some sight, some speech, some mobility? How much debilitation and pain - neurologic suffering - would we endure, or have a loved one endure, in the hope of - just the chance of - a few more... ? a bit more... ?

Paul Kalanithi had trained his mind, his eyes, and his hands to retrieve and perhaps reclaim, to salvage and perhaps restore, identities by freeing the brain of alien impediments. To those skills, he added pastoral sensibilities - along with physiological realism.

Neurosurgeon as arbiter, and adjudicator

Paul Kalanithi sought to "forge a relationship" with the "identities" of each patient, so that he could best decide what to do - or not do - inside their respective skulls.

"As my skills increased, so too did my responsibility. Learning to judge whose lives could be saved, whose couldn't be, and whose shouldn't be requires an unattainable prognostic ability. I made mistakes. Rushing a patient to the OR to save only enough brain that his heart beats but he can never speak, he eats through a tube, and he is condemned to an existence he would never want....

"I came to see this as a more egregious failure than the patient dying. The twilight existence of unconscious metabolism becomes an unbearable burden, usually left to an institution, where the family, unable to attain closure, visits with increasing rarity, until the inevitable fatal bedsore or pneumonia sets in. Some insist on this life and embrace its possibility, eyes open. But many do not, or cannot, and the neurosurgeon must learn to adjudicate."

"Before operating on a patient's brain, I realized I first had to understand his mind: his identity, his values, what makes his life worth living, and what devastation makes it reasonable to let that life end."

An image of one's self - planning for the unplanned

The CT scan images showed that "the lungs were matted with innumerable tumors, the spine deformed, a full lobe of the liver obliterated. The cancer was widely disseminated." Stage IV.

Paul Kalanithi would be seen by a lung cancer oncologist in the very hospital room in which he had seen hundreds of his patients.

Getting too caught up in statistics (survivability odds) was, to Kalanithi's mind, like trying to quench a thirst by drinking salt water. Only 0.0012 percent of 36-year-olds get lung cancer. Those odds triggered dialectics. He shares with us his sorting through existential questions: Given my diagnosis, and prognosis, what makes me most sad? Given my diagnosis, and prognosis, what I am afraid of?

He had always been a striver, for good, even breath-taking work, as a neurosurgeon and a neuroscientist.

In one realm or another, to one capacity or ability, or another, to one degree or another - we are all strivers. If any of us had a crystal ball, or reliable tea leaves or tarot cards, or some such - we would prioritize our strivings, accordingly. We'd put off, or abandon some; we'd make way for those that are really important to us - strivings that would really count in the end.

Rather than death's enemy, death's ambassador

When Breath Becomes Air allows us to become more keenly aware of death's biological and experiential components.

"As a resident, my highest ideal was not saving lives - everyone dies eventually - but guiding a patient or family to an understanding of death or illness."

"When there's no place for the scalpel, words are the surgeon's only tool."

"The families who gather around their beloved - their beloved whose sheared heads contain battered brains - do not usually recognize the full significance.... They see the past, the accumulation of memories, the freshly felt love, all represented by the body before them. I see the possible futures, the breathing machines connected through a surgical opening in the neck, the pasty liquid dripping in through a hole in the belly, the possible long, painful, and only partial recovery - or, sometimes more likely, no return at all of the person they remember. In these moments, I acted not, as I most often did, as death's enemy, but as its ambassador."

A pastoral role

"I had to help those families understand that the person they knew - the full, vital independent human - now lived only in the past and that I needed their input to understand what sort of future he or she would want: an easy death or to be strung between bags of fluids going in, others coming out, to persist despite being unable to struggle."

For a patient's well-being - and for the well-being of that patient's family and loved ones - Kalanithi worked at actually, authentically, informing the standard informed consent. He saw the authorization not as an administrative necessity (and hurdle), but as an opportunity to elicit, become acquainted with, come to appreciate and counsel patients and their loved ones.

For him, this was not a pro forma, perfunctory process: Those meetings were much more than "a juridical exercise in naming all the risks as quickly as possible, like the voiceover in an ad for a new pharmaceutical." Instead, those exchanges were exploratory and expository, revelatory; an opportunity for discovery; "an opportunity to forge a covenant with a suffering compatriot."

Conclusions - Communions Paul Kalanithi - neurosurgeon extraordinaire and neuromodulation-neuroscientist (writing signals into the brain) - revered literature. He held language to be "a supernatural force... bringing our brains, shielded in centimeter-thick skulls, into communion."

Paul Kalanithi - neurosurgeon extraordinaire and neuromodulation-neuroscientist (writing signals into the brain) - revered literature. He held language to be "a supernatural force... bringing our brains, shielded in centimeter-thick skulls, into communion."

He described his sufferings but we are left holding on to his reflections: "Words have a longevity that I do not have."

Even as we are saddened by what is so intimately documented in When Breath Becomes Air - we are instructed, in a most kind and gentle way. The memoir is communicative and thought-provoking, without a scintilla of the pedantic or the didactic. We come away thinking about our own aspirations and trajectories, and we hope - we really really hope - that if we are ever under the scalpel, saw, and drill, that our neurosurgeon is someone very much like Paul Kalanithi.

--------------------------------------------------------

Brain schematics: McGill University and The Brainwaves Center

Photo: Norbert von der Groeben/Stanford Health Care