Automation could revolutionize architecture--by eliminating architects.

Seven years ago, in my then-column for Architect magazine, I wrote that computerized automation eventually could fulfill the ultimate aims of green building by achieving dramatically better performance. Now the same magazine has taken up the same topic in a couple of recent articles. In June, Daniel Davis declared that architecture can't be completely automated because "it is--for now--impossible to get computers to think creatively." Last month, Blaine Brownell echoed this sentiment, citing a new McKinsey report claiming that "creative tasks are largely immune from automation." Yet, the implications of automating creativity are much bigger than either author lets on.

"Robot replacement is just a matter of time," wrote Kevin Kelly in Wired a few years ago. "It doesn't matter if you are a doctor, lawyer, architect, reporter, or even programmer." Robotic manufacturing and other advanced industrial technologies are familiar, but computers also have taken on many white collar tasks, including customer service, journalism, and web design. Kelly says nothing more of architects, though automated processes already are changing the profession. Computational design and parametric modeling are routine in architectural practice now, but often they merely facilitate architects' pursuit of exotic geometry. Hi-tech eye candy. What's still relatively rare is employing advanced techniques to improve performance significantly, and what's nearly unheard of is automating the creative process entirely.

This is how designers work: We study a variety of possibilities and choose the ones that work best or we like most. Automation potentially can improve every aspect of this process and become, in Kelly's words, "better than human."

First, innovation involves generating a large number of ideas to find a very few remarkable ones. Computers can study thousands of variations in the time it takes a designer to look at dozens, discovering possibilities that might never occur to us. As Davis reports, Autodesk, which makes the most popular computer-aided design (CAD) tools for architects, is developing software that "learns the same way we do," only faster, says the company's chief technology officer, Jeff Kowalski. "This is the biggest, most fundamental change that I've ever seen coming our way."

Trouble is, the way architects normally use computers is to enhance, refine, or document our ideas, not to generate new ideas altogether. As I wrote last month, the architect-as-artist is driven toward highly personalized visions, and we often sacrifice other priorities along the way. In other words, what we like isn't always what works best, and this could be holding back the entire profession.

In Paris this month, world leaders pledged to shrink greenhouse gas emissions markedly, and they cannot accomplish this without the building sector, which is responsible for nearly half of energy and emissions in the US alone. However, a typical "high-performance" building achieves fairly modest energy reduction--25-35 percent, according to the US Green Building Council and the American Institute of Architects. And those numbers have flat-lined in recent years, so the industry is stuck, it seems. Yet, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory calculates that adopting current best practices can nearly double that outcome, getting to 50-60-percent reduction, without any additional costs. Applying that to every building could cut the total annual US emissions by a quarter, half the amount needed to stabilize the climate by 2020, according to estimates. While the information needed for architects to raise the bar is readily available, most of us don't use it, but it's easily be automated: for example, the engineering firm Thornton Tomasetti has developed automated tools to optimize structures for cost and carbon footprint. With the stakes so high, and human architects not stepping up fast enough, maybe Kelly's right that "robots will--and must--take our jobs."

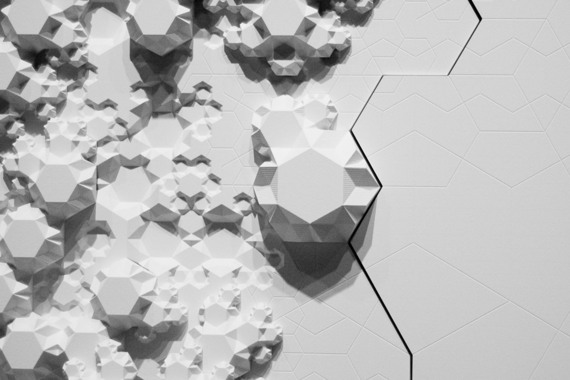

Aranda/Lasch, "Rules of Six"

What of beauty? Architecture isn't strictly about saving money and resources, after all. As I write in my book, The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design (2012), a growing wealth of research is revealing how people respond to light, space, form, pattern, texture, and color, and much of this information could be automated during design. "Beauty is merely a function of mathematical distances or ratios," explains computer scientist Daniel Cohen-Or. He and a team invented a "beauty engine" that subtly improves photos--with an 80 percent success rate, according to their polling. The "computational aesthetics algorithm" CrowdBeauty, launched this year, mines millions of photos on Flickr to find overlooked images with exceptional composition, pattern, color, contrast, and brightness. As the MIT Technology Review put it in May, "These guys have taught a machine ... to recognize beauty."

I know of few places more gorgeous than an Aspen grove in autumn, but there's no "design" there--just genetic coding and environmental conditioning. Architects Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch have used automated techniques to emulate the growth patterns of nanostructures, and Portuguese artist Leonel Moura has applied artificial intelligence to generate architectural forms by mimicking the emergent behavior of ant colonies. With sufficient computational power and speed, buildings could evolve the way any living system does and make design cheaper, faster, smarter, more efficient, more sustainable, and more beautiful.

Naysayers are plenty. Last February in the New York Times, Nicholas Carr declared that "robots will always need us": "We exaggerate the abilities of computers even as we give our own talents short shrift." Architects agree: "Technology is important," Jacques Herzog told Vanity Fair in 2010, "but computers cannot do anything without the assistance of the human brain." Yet, according to estimates, machines soon will exceed the computational abilities of the human brain--possibly in the next handful of years but certainly during this century. Just this month, Elon Musk launched the OpenAI project specifically to "surpass human intelligence." In his book, The Glass Cage: Automation and Us, Carr himself confesses that just a few years before Google created a self-driving car, many experts thought it couldn't happen.

Cognitive scientist Margaret Boden defines creativity as "the ability to come up with ideas or artifacts that are new, surprising, and valuable." Because machines can demonstrate all three, Boden maintains that debates about creativity and computers really are disagreements about what we value. "To accept robot creations as artistic expression," Moura tells me, "means to deny humans the exclusiveness of creativity, and many people are not willing to do this."

Artificial creativity isn't science fiction--it could be the future of architecture. The only thing holding it back is architects themselves. Can we get smarter about solving serious new challenges, or will we risk becoming obsolete?

Follow Lance Hosey on Twitter: @lancehosey