No one likes to be put on hold but as life's certainties go, "please hold" is right up there with death and taxes. When a customer service rep finally does take your call, he or she might just as well say: "Please work." At least that's pretty much the case when you're contacting the telecom behemoths, one of which almost just got more monstrous with Comcast's attempt to swallow Time Warner Cable.

That didn't happen, but even if it had it probably wouldn't have changed the curious nature of the working relationship that has evolved between millions of customers and these communications-oriented companies that are uniquely wired into our personal and professional lives, like an extracorporeal nervous system.

Anytime our telecom connections falter - namely TV, internet, telephone - most of us go into unflattering paroxysms that require calling an 800 number for relief. First we are typically put on hold, of course, but then a customer service rep almost inevitably enlists our help in trouble-shooting whatever our technical difficulty seems to be.

It would be one thing if our woes, whether wired or wireless, took just a few minutes to resolve, but these calls to telecoms can drag on for hours. I still marvel at having once been on the line for nearly eight hours - a full working day! Just recently I was reminded yet again that we, the customers of the United States, have tacitly allowed ourselves to be drafted into a volunteer corporate army of sorts. We're like a shadow infantry of trouble-shooters, working on the front lines of our communication lines to keep them from breaking down like so much frayed cable.

Working for The Man is one thing, but somehow we have wound up volunteering for The Man.

There have been studies showing that the average American can look forward to racking up a lifetime total of somewhere between six weeks and a full year on hold. But I have not found the study that calculates the many hours that customers put in as trouble-shooters, undoubtedly saving the telecoms millions of dollars in the process. It's an interesting arrangement, since most service providers - like plumbers, electricians, roofers and car mechanics - don't usually expect their customers to lend a hand, as if they're unpaid interns.

What's more, our technical difficulties are really as much a problem for the telecoms as for us: If we're not properly connected, we can't be paying customers.

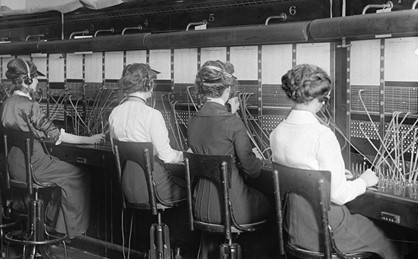

But somewhere around the dawn of the Internet's dial-up days and the Big Bang in cable and satellite TV services, customers became accustomed to taking an active role in fixing their finicky systems, often with a company rep on the phone giving orders, like a softer-spoken breed of drill sergeant. Obviously telecom service workers still show up for certain jobs - like those involving climbing ladders, stringing lengths of cable or affixing satellite dishes - but a lot of essential jobs fall to customers themselves.

My latest act of pro bono problem solving was especially striking because I hadn't even called a certain telecom company for help. All systems were go. It was the company that got in touch with me about installing a new modem with a built-in wireless router to speed up the flow of Internet data. I found out that I'd receive a new unit in the mail - and I was to install it. What struck me was that the concept of the volunteer corporate army has apparently become so well accepted, by companies and customers alike, that the telecoms themselves may initiate calls to their customers for service, rather than the other way around.

I of course heeded the corporate call, which came with assurances that this modem-switching process would take just a few minutes. But as a veteran volunteer who is by now familiar with a modem's modus operandi, I knew I had better carve out more than mere minutes for the supposedly quick and easy task at hand. Indeed I was only at Step 2 in the written instructions before the instructions failed to match the reality of the job I was trying to do. So I had to call the 800 number - and added about another five minutes to my lifetime tally of time spent on hold.

Then I got down to business with a representative named Meg, who ordered me through a series of clicks on my computer screen quite different from what was described in the instructions. After talking me through the initial steps Meg asked if there was anything else she could do. At that juncture it was going to take me a little while to complete the next steps, which included unplugging and reconnecting several phone lines and cables, and Meg didn't seem eager to be left waiting on hold - ironic, perhaps, but presumably I was now well on the road to reconnection, having rendered myself disconnected to do this modem installation job.

I hardly need to repeat the details of what happened next, so familiar is this sort of scenario with those large companies whose names we so often embellish with four-letter descriptors. Suffice it to say that, not long after my initial conversation with Meg, I had to call the 800 number a second time. I re-explained my problem, took orders from another rep, eventually got transferred to another, and then another, until I was reasonably sure my precious data flow had returned to normal, along with my heart rate and blood pressure.

This latest trouble-shooting tour of duty, which the company itself had initiated, had taken nearly three hours - an improvement over that eight-hour day I once spent, but still. It somehow seemed unfair. When I grumbled out loud about the hours that had passed since my initial call, Debbie, my final customer drill sergeant, offered to put a $15 credit on my account. At first I thought she had said $50, which sounded more equitable, considering my usual rates when working for The Man, but of course I had volunteered - what else could I do?

I gladly accepted the credit, but it was still hard not to feel taken advantage of, as I have after other such drawn-out calls. So I try to tell myself that all of this voluntarism is for the greater good of the growing communication grid. And someday, when the grid hums along with scarcely a glitch, we can regale our children and grandchildren with tales from the digital trenches that'll seem as distant as the frustrations of programming a VCR (a what?) or finding a phone booth (a what?!!).