When the U.N. General Assembly adopted The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in December 1948, it essentially stipulated the right for all people to a decent job with decent pay and social protection in the case of temporary unemployment that would lift them back into the workforce. This made sense for the industrialized economies that made up the U.N. at the time and that were yearning for prosperity and social justice after the devastating years of World War II.

But even 65 years after the Human Rights Declaration, the empirical reality of many developing and emerging markets is starkly different. According to the Gallup world poll less than half of all working-age adults globally have regular employment of more than 30 hours a week. According to the International Labor Organization, only 20 percent of the world's population has adequate social security coverage such as a pension or health insurance and more than half lack any coverage at all. In the least-developed countries fewer than 10 percent are covered by social security. This reflects the structure of the underlying economies and their large share of informal and self-employment. Fiscal constraints mean that many middle and low income countries will likely not be able to deliver universal rights-based social protection in the foreseeable future.

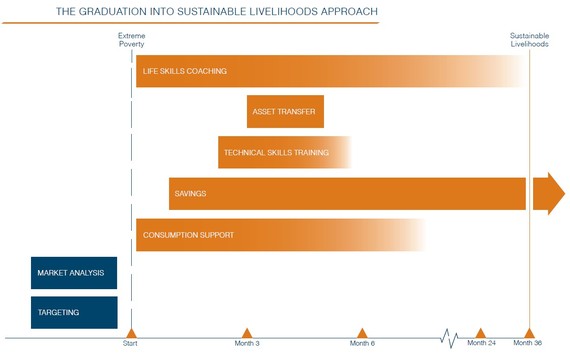

Against this reality, Southern practitioners have felt an urgency to experiment with new approaches that help the extreme poor to graduate into sustainable livelihoods. This "graduation approach" was originally pioneered by BRAC in Bangladesh and is now being adopted in a number of other countries. The approach combines a sequenced mix of interventions. Participants receive consumption support, access to savings services, technical skills training, a variety of assets and regular life skills coaching over a period of 18-36 months. The goal is to help them create livelihoods that will end a lifelong existence in abject poverty.

At a gathering last month in Paris, some 100 leading policymakers, practitioners, researchers, and development experts gathered to exchange learnings from graduation pilots around the world and to examine how the bottom-up graduation approach can be incorporated into top down government social protection policies in order to reach the extreme poor at large scale.

One of the strong impact narratives emerged from the rigorous evaluation of the original graduation program in Bangladesh. There, BRAC and researchers from the London School of Economics cooperated to randomize the roll-out of the program across more than 1,400 communities. This allows a comparison of the effectiveness of the program by looking at the families who were early participants and comparing them with families who will only benefit later. Over three bi-annual surveys, the researchers have created a rich database covering more than 26,000 families.

Participants in the graduation program increased their income by nearly 40 percent over the control group. This increase was largely due to more hours worked and less to an improvement in productivity. Half of the extra income went into higher consumption, the other into more savings. Participants also experienced health benefits as well as improvements in nutrition and education. LSE's Robin Burgess at the Paris event interpreted the data to show that the extreme poor in the BRAC program were severely under-employed at the outset. With the opportunities provided through the graduation program, their labor hours became more evenly spread across the year. They started getting out of seasonal, daily wage labor for landlords or others and increased their income from self-employment. Essentially, they began to successfully mimic the working profile and choices of the rural middle class they had observed; the incidence of other activities increases. The poor started to accumulate assets outside of those transferred by the program. This interpretation is consistent with Esther Duflo's analysis of a smaller pilot in West Bengal highlighted in an earlier blog.

Behind the research findings are firsthand stories of individual success. For example in Ethiopia, Asqual Gimay, 31, a single mother living with her seven year-old-daughter, her ailing mother, and a divorced sister had no land, limited access to food and very little cash income when she joined the CGAP-Ford Foundation Ethiopia Graduation Pilot: "I'm usually not lucky, so I'm happy I got a chance to be in this program," she told researchers at the outset. As part of the program, Asqual chose to start a bee-keeping business, with a clear goal in sight: "I want to be rich because I have suffered for a long time because of my poverty." Her business expanded rapidly during the program: in 2012 she had 10 bee colonies and still occasionally worked as a daily wage laborer to earn extra cash.

She also managed to save 12,000 Ethiopian Birr (approximately $USD 645) at a local microfinance institution: "Now I feel confident that I can provide for my daughter in all ways -- material and otherwise. I can even cover the cost of [her] long term study. I can buy her enough clothes. Now I want a separate house and stop crop-sharing. I want to buy oxen and hire paid laborers instead."

Asqual Gimay, CGAP-Ford Foundation Ethiopia Graduation Pilot Participant. Photo Credit: BRAC Development Institute*

At the global level, the extreme poor are those living with less than $1.25 a day, estimated in 2012 to be nearly 1.2 billion people. Individual countries may use higher poverty lines, but however defined, the extreme poor tend to be food insecure, lack education, usually have few or no assets and are limited in their options to make a living. They often live on the outskirts of society and lack self-confidence or opportunities to build the skills and resilience necessary to plan ahead.

I realize that not everyone will be as successful as Asqual: the Graduation Approach is not a silver bullet to ending extreme poverty. But it seems to hold real potential, in particular if the NGO sector, governments and the international development community can team up to scale the successful elements of the approach in the context of national safety net policies.

*Asqual Gimay's story is summarized from Pathways out of the Productive Safety Net Programme: Lessons from Graduation Pilot in Ethiopia, BRAC Development Institute (BDI), 2012. Since 2010, BDI has been conducting qualitative research at the Ethiopia Graduation Pilot, following the lives of 22 participants.