This semester, I taught a repugnant movie. On purpose.

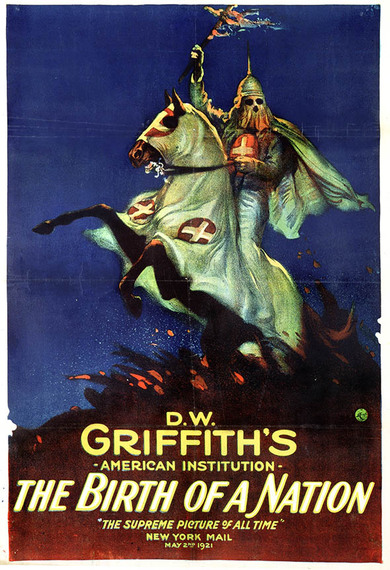

In my film class at Baylor University, I assigned--and my students and I discussed--D. W. Griffith's 1915 epic The Birth of a Nation. This early American feature film, adapted from Thomas Dixon's polemical novel The Clansman, follows the intertwined stories of two families--one Northern, one Southern--through the Civil War and Reconstruction, and ends with a stirring finale as the Ku Klux Klan rides to the rescue of white womanhood and civilization. Although African-American characters are among its prime villains, they are played by white actors and actresses in obvious blackface--which may be the most appalling of the film's many appalling elements.

The Birth of a Nation captured the imaginations and inflamed the passions of the nation when it first appeared. It was responsible in a very real way for the birth of the Hollywood film industry as we know it--and also for the early stirrings of film censorship. It doubled the membership of the NAACP--and also relaunched the Klan. It was, for many years, the top-grossing film in American history, and, adjusted for inflation, would still be one of the most popular films of all time.

Like a silent film version of Donald Trump--if such a thing were possible--it simultaneously embarrassed and enticed with its strident blend of racism, appeals to earlier values, and ability to entertain. But today, The Birth of a Nation is rarely taught and rarely seen in its entirety. James Baldwin wrote that it was clearly a work of artistic genius. It was also, he said, "an elaborate justification of mass murder." As I told my students, a work of art can, sadly, be both.

So it goes, down to the present day. The Birth of a Nation occupies a strange shadow status in our culture, one of the most important American movies ever made, yet one that is rarely watched and even more rarely discussed. It is a work that deals with some of our most fundamental American conflicts, but it has been pushed outside of public discourse. American Movie Classics sometimes airs it (with elaborate presentations of its historical and critical context), but still receives heated protests. Many college professors fear that students won't be able to talk critically about a work so blatantly ideological about the superiority of whites and the inferiority of others, so they don't teach it, or show only snippets. And when the film was named to the National Film Registry, the Library of Congress' index of major American films, the action was roundly condemned.

Some people are offended by the movie's racism.

Some are offended by having to talk about the movie's racism.

But this failure to talk about the past and its implications for the present (so well represented by this movie from the past about the past) seems to be the problem we find throughout American society. We are finding it harder and harder to talk about race these days, and often when we do, we enter those conversations with our minds already made up. As this summer's Pew Research Center report on racial attitudes in America suggests, we have become calcified in our thinking about racism. If we are white, it's possible that we are sick of talking about it, and may even believe it is no longer an issue. If we are people of color, we may be sick of talking about it because nothing seems to change, even though we believe it is certainly still an issue.

In refusing to have conversation about The Birth of a Nation (or about other works that deal directly or indirectly with the question of race, prejudice, and how our culture thinks about them), we are missing out on a prime opportunity to have conversation not about our own entrenched positions, but about the entrenched positions of the characters in a story--which takes us, often, from a different starting point, and so can lead us to some different conclusions. Over the years, I have taught Huck Finn many times at Baylor, and while that work too is tinged with racism, it also offers us the chance to have conversation about what makes us all human.

We begin with suspicion; we end, if all goes well, with some understanding.

Earlier this year, an Episcopal priest invited me to lead a retreat on race and film for his inner-city mixed-race parish. Although they worshiped together on Sunday and worked together on peace and justice issues all week long, his congregation had never, he said, had hard conversations about race.

They had not truly talked to each other about who they were, how they saw themselves, and how they saw others--and he was ready to finally have that conversation.

So over the course of a weekend together, we watched Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, Do the Right Thing, and Crash. We talked about how those films had been viewed by their original audiences, what they seemed to be about, and how we received them now.

We were offended and inspired. We agreed and disagreed with the decisions made by characters. We told our own stories, and listened to those of others.

And in the process, we had a powerful conversation about race--and perhaps more importantly, about the powerful human connections that unite rather than divide us.

I would never show a film or teach a book just to shock someone, and as a child of the American South, race and prejudice remain my most sensitive issues. But sometimes--as with The Birth of a Nation--a text that offends all or many can also open a window into a new way of seeing the world, which is what every teacher hopes to do.

That's while I'll continue to be appalled by The Birth of a Nation.

And why I'll continue to teach it.