While the annual era of hysteria is upon us here in Hollywood -- the Oscars! -- there's another one that'll last long after the Academy's fanfare has died down. Pilot season is that glorious 4ish-month period during which all the would-be fall TV hits scamper to cast and crew up with the right mix of talent to steal the hearts of viewers and tweeters everywhere, and all the would-be fall TV stars audition like mad to earn the chance to be those ones you love... or just to book a damn job.

But I'm a dialect coach. And for me pilot season means fielding a deliciously random assortment of accent requests from said actors vying for their big break:

I need to lose my northern British and pull off New York cool!

What does medieval Russian sound like??

Can I get them to mistake my French accent for a Japanese one??

What is Salem-witch-trial-era colonial speak?

For most actors, talking in silly accents is fun -- an easy-access party trick, a dramatic flair when telling anecdotes to friends and family. But when they actually have to pass as someone from a foreign land in an audition room in front of people who may actually know good from bad? Then daunting is more the name of the game, along with choice expletives and rising terror. Which are all rather effective fun-squelchers and most certainly death to good acting.

When I moved to New York City in the mid-aughts, MFA papers in hand and acting on the brain, I was, to my surprise, thrust within seconds into coaching off-Broadway. It made a kind of sense; here was a chance to mix my unbridled affection for actors and acting with some other knacks I'd picked up along the way: a good ear, a shameless nerdiness when it comes to text analysis, and an irrepressible giddiness about how language and communication works and how it evolves. Really, if I'm being honest, I had always been drawn to the fine art of talking in funny voices -- dating back to my obsession with My Fair Lady as a wee kid shouting "move your bloomin' ass!" at what were surely inappropriate moments. But it never occurred to me back then that I'd one day play the Henry Higgins role in real life (with fewer marbles and less misogyny, one hopes).

And then there I was in the city, an English major and theater geek who'd fallen into a hot love affair with the International Phonetic Alphabet (the secret code for decoding dialects) thanks to some brilliant mentors -- now suddenly on the receiving end of a bunch of dialect gigs these mentors threw my way when they had a surplus. Impostor syndrome bedamned: during that first year or so I helped an actor go British ("RP") for a Frank Langella production of A Man for All Seasons and an actress go Katharine Hepburn-esque for a play about one of Hemingway's wives, journalist Martha Gellhorn. I coached Rwandan and Aborigine and dirty modern London and clean old-timey London and Nuyorican and Irish and Bosnian and a mythical Georgian town and "Standard American" and "casual American."

(For an example of the difference between those last two, say out loud as though you're pissed at your significant other, "Fine, just do what you want." Did you say "whatchyoo" with a full-on "ch" sound in there? Did you make a t-sound at the end that puffed air out or, more likely, not? Voila, casual American. A totally legit, contemporary accent that's pretty darn useful for TV and film but could use a little tweaking for Hamlet.)

Now in Hollywood I get fewer American clients needing to sound foreign than I did in New York, and more foreigners needing to sound American. But whether they're native or not, and whether I'm hired on a film or TV set or working one-on-one with an actor at my home office, the dance is basically the same:

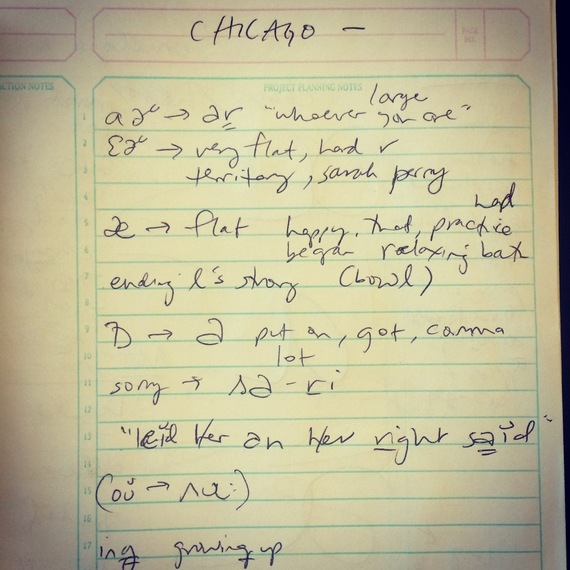

Half of it is the technical act of teaching the sound differences between one accent and another -- focusing on the biggest consistent vowel and consonant changes between the actor's own accent and the accent he or she is learning, and how those new sounds feel in the mouth. If you're from Southern California and have to sound Chicago for an audition, the first sound we'll focus on is probably the "o as in honest" sound, which switches to an "a" that you might think of as "a as in apple" but actually more closely resembles the Spanish "a as in salsa." So "mom" becomes "mAHm!" (This is a much more exact science when you can read the International Phonetic Alphabet, but I never expect my clients to be into that -- unless they're my students or former students at Stella Adler Conservatory and then you better believe they're breakin' that secret code like they're Benedict Cumberbatch in The Imitation Game.)

The other half of what I do is the kooky, inexact part, a mix of psychological and sociological nerve-calming, so that the above can actually be learned and embraced and integrated and adored (in that order). The fact is, the act of picking up a new accent inevitably arouses all kinds of internal drama, whether the client is new to acting or a big, fancy TV star. And whether the drama is conscious -- "I don't sound like myself anymore! I suddenly can't trust my instincts! I'm not even thinking about the meaning of the words! HOW WILL I EVER ACT AGAIN?!" -- or unconscious, manifesting itself in held breath, a flushed face, contorted muscles, even the most preternaturally blasé supermodel losing her cool at my dining room table.

Learning to speak with a new accent, like picking up most new skills, takes courage. And it can and should be fun to be this courageous -- to push through the fears and the rising panic and seize one's inner heroism and a whole new identity -- but of course it helps to have someone there to cheerlead the process, reflecting back that hero-in-the-making. I get to do that. And it's awesome.

But it's not just awesome, it's also serious business: many actors who do not come from money or who feel otherwise disenfranchised, reflect this disadvantage in their voices. From black actors who get typecast as thugs to girls who fight to be taken seriously as leading ladies because their voices peg them as ditzy and/or evoke Kim Kardashian ("sexy baby voice" or the much maligned "vocal fry"), it's pretty clear that how we speak plays a large role in how we're perceived -- and can dramatically affect our livelihood on stage and screen. If not in the boardroom. The thing about learning accents, and learning more about how our instrument works in general regardless of profession, is that it offers us choices. And choices are what disenfranchised people lack. Speech awareness and a bit of technique frees everyone -- no matter their background or self-professed identity -- to play different aspects of the human experience, with honesty. To have the tools to make choices.

We are large, we contain multitudes, and it's rather satisfying to try on different versions of ourselves and admire the fit. That's why most actors are in this business, after all, and why they fight through the Hollywood crap to stay in it. And it's probably why most of us tune in to watch them -- to lose ourselves in characters nothing like us, who nonetheless illuminate something about ourselves.

Let's hope the next crop of shows gives us that chance, and that those actors find their way back to the fun of it all. Me, I gotta hunt down the linguistics files on those pesky late-1600's Puritans.

For more, check out LADialectCoach.com. An earlier version of this post appeared in MsintheBiz.com