Let's start the debate about trade policy on the right foot. Everyone I know is "for" trade. A better question is, "Who gets the gains from trade?"

Gains from anything, trade included, can be divided in 3 ways.

- Someone might give you your share of gains, for whatever reason.

- You might take your share, if you have power.

- You might get nothing, or possibly lose what you have.

Option 1 presumes some level of trust. Microsoft's CEO, Satya Nadella, projected that sentiment onto women, when he told them to be patient and not ask for raises. Their bosses would recognize their value and reward them in due time. Nadella and other CEO's are accustomed to power. He was probably expressing benevolence, muddled with sexism.

Ultimately, power relationships determine how gains are shared. If you have power, you get gains. If someone else has power, they get gains. If power is balanced, then gains are more likely to be shared.

Nadella's paternalism is reflected in an edgy cliché told about trade policy, "Sure, trade creates winners and losers. The winners could compensate the losers." Right. Winners might voluntarily compensate losers, but the point of being a winner is to win, not to compensate someone else!

Where do workers get power? I remember a time when unions made demands. They could strike to increase their share of gains from productivity and work. Union contracts would then set standards for employment generally.

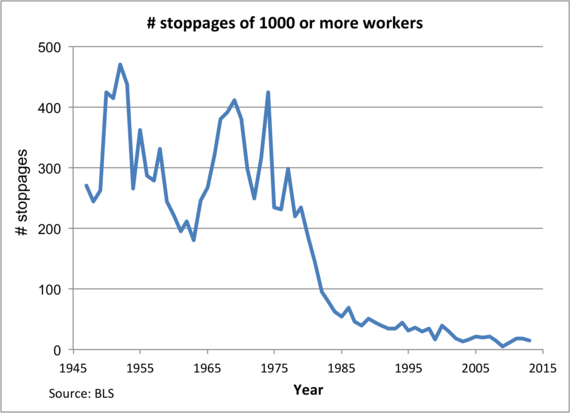

Figure 1. Large works stoppages over time.

In the late 70's that power started to evaporate.

The message in Figure 1 is actually more dire than it appears, because it includes both strikes and lockouts. Employers lock out employees to force concessions. Lockouts are the opposite of workers striking to demand gains.

Lockouts are becoming more common, while strikes are becoming more rare. The NFL, NBA and NHL work stoppages were lockouts. Steelworkers in 2015 - locked out. Art handlers(!) at Sotheby's - locked out. Bakery workers at Kellogg - locked out. The last strike by west coast Longshore workers was in 1971. Since then, lockouts.

When I was on strike in 2000, I was startled by an offhand comment that strikes were more about keeping what we have, and not so much any more about increasing our share of gains. One of our strike messages was "no medical takeaways." (We had other, more uplifting messages.)

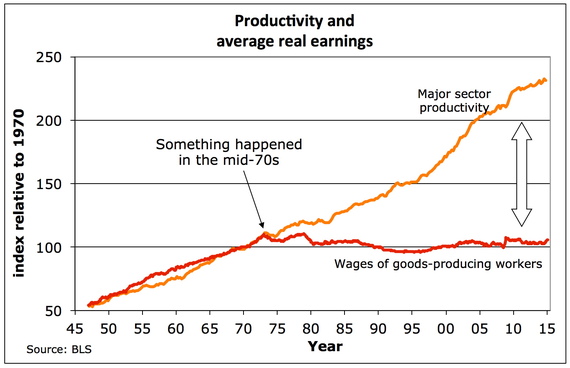

The message in Figure 2 is that in the post-war period, productivity gains were shared with workers. The social principle then was, "We all do better when we all do better." Social movements enforced that principle for civil rights, women's rights, and the environment.

Something happened abruptly in the mid- and late-70's to shift bargaining power away from workers and in favor of employers. Actually quite a few things happened, not the least of which was shredding the social contract. One aspect of that was to weaken the employment relationship, making workers feel more contingent and precarious.

By the 80's our new social principle became, "I can do better at your expense."

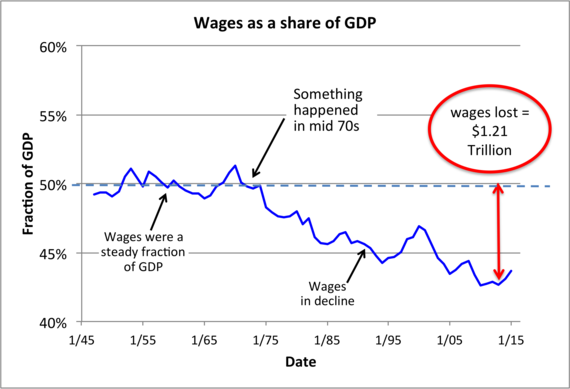

Figure 3 illustrates two ways of sharing gains in the post-war period. In the post-war period, we did share. After 1973, we stopped sharing.

"Labor share of GDP" includes income for everyone - regular workers, as well as CEOs, the top 1%, .1% and .01%. Since the mid-70's, CEOs and hedge fund managers have taken additional billions in income, but that is more than offset by relatively smaller incomes for everyone else.

Under our current trickle-down policies, our economy - overall - is under-performing by $1.21 trillion dollars.

Trade deals define power relationships in the global economy. Globalization, as we manage it, is administered by global financial institutions. The WTO, IMF, and World Bank are devoted to investor interests. We have no corresponding democratic political institutions at the global level, for balancing public interest with business interests.

The power relationships in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) are pretty clear - investors first; workers and communities last. Six of the 12 TPP countries fail to meet global standards for human trafficking. Malaysia, one of our TPP "partners," has consistently been among the worst in the world for forced labor in its electronics and garment industries, child labor in its palm oil industry, official corruption, and exploitation of thousands of refugees from Thailand.

One influential Member of Congress told a group in Seattle he preferred to "engage" with Malaysia by letting them into TPP immediately. Malaysia could prosper. Then workers in Malaysia could work themselves up from slavery to freedom.

Actually, slavery doesn't work that way.

President Obama promised us better. He would hold Malaysia and Vietnam to high standards. We could have told Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei to meet basic labor standards, first. Then they could "dock" in to TPP, like any other country. That would give an advantage to workers in those countries.

Instead, the President back-flipped. Our trade negotiators reportedly pressured the US State Department for an artificial upgrade in Malaysia's annual ranking on trafficking in persons, so TPP could qualify for Fast Track consideration in Congress.

Thailand and Indonesia are in the queue to dock into TPP, even though their fishing industries are notorious for 21st century slave labor.

Our negotiators' indifference to workers and environmental protections makes us wonder how low would we go to help US companies get electronics components and palm oil from Malaysia, or tennis shoes from Vietnam, or shrimp from Thailand.

We have never enforced environmental standards in any trade agreement.

Years after CAFTA, Guatemala is arguably the most dangerous country in the world for labor leaders. Honduras is arguably the most dangerous country for environmentalists. Under the US-Colombia trade deal, Colombia is still notorious for violence. Mexico has flaunted its labor obligations under NAFTA for decades. Peru has backed out of its historic commitments for labor and environment in the US-Peru trade deal.

Our trade policy encourages producers to move work to low-wage countries with weak worker protections. The global oversupply of labor and the threat of offshoring work overshadow almost every labor contract negotiation in America. That threat chokes off bargaining power for workers around the country.

Nothing in our trade policy increases workers' power, or positions us to share gains from trade. It is no surprise that workers' wages have decoupled from productivity. Workers continue to create gains, but those gains are swept up by a tiny few. That is a predictable outcome from the unbalanced power relationships built into our trade and other policies.

A good trade policy would have real protections with meaningful enforcement, and effective institutions that will follow through on commitments. That's what global investors designed for themselves in the blizzard of trade deals, and that's what they have in their global institutions, such as the WTO, IMF, and World Bank.

Larry Summers(!) and Hillary Clinton called for a "rethink" on trade. Amen. The sooner the better.