Is that the "Laughing Buddha"? Yes and no. This jolly character got his start in tenth-century China. A Chinese Zen text dated 988 tells of an eccentric monk who "wandered around with a cloth sack," asking for food and playing with children. His nickname was "Cloth Sack" -- Budai in Chinese, Hotei in Japanese. Entering popular culture, he became the Laughing Buddha or the Fat Buddha. The painting above is Japanese, so I'll use Hotei (pronounced hoe-tay).

In Buddhism, Hotei is distinguished from Buddhism's founder, who lived in India in the fifth century B.C. His many names include Shakyamuni, the Buddha, the historical Buddha. Shakyamuni is almost always depicted as slender. You can't tell a Buddha by his belly, but you can tell the Buddha by his lack of one.

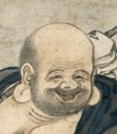

Zen played a central role in East Asian art and culture for nearly a thousand years. Painting, calligraphy, poetry, gardens, Nō drama, the tea ceremony, and other arts were valued as expressions of Zen. The image above is a scroll by one of Japan's greatest painters, Kanō Masanobu (1434-1530). Kanō's synthesis of Chinese and Japanese elements influenced Japanese painting for centuries.

The scroll shows a stocky, somewhat underdressed man traveling on foot. A huge sack hangs from a walking stick over his shoulder. His robe is -- or was -- the robe of a monk. His right hand touches his ample belly. Turning his head, he laughs.

Kanō's skill as an artist deserves a closer look. His brush strokes are rough on Hotei's robe and bag, meticulous on the face and body. Two flow lines add energy: the upward line from Hotei's elbow to the end of his staff, and the downward line from his elbow to the end of the robe. The bag and the belly seem to be in balance. The background is completely empty.

This fellow would certainly stand out in a crowd. His forehead is elongated -- a sign of a sage, according to Daoism. His earlobes are also elongated -- in Buddhism, a mark of spiritual attainment. His eyes are twinkly, his nose slightly askew. Some aspects of the painting are cartoonish.

Call it what you will -- contentment, happiness, freedom -- Hotei seems to have found it. If he is carrying everything he needs in that sack, he is not burdened by belongings. If he knows his mind, he is not burdened by thoughts. Zen's sense of humor usually involves some combination of spontaneity, playfulness, irreverence, and insight. Kanō's Hotei embodies those, too.

The painter brings his subject to life by zooming in to a specific moment. Has Hotei just heard the voices of children? Or smelled some food? Maybe he's laughing at himself. In images of Hotei by other artists, his joy is so radiant that it must be the joy of enlightenment. A scroll by Mokuan Reien (d. 1345), though faded, captures this elusive quality:

Like a temple bell or a cogent haiku, Hotei keeps resonating. Exposing his belly is symbolically equivalent to manifesting his true nature, his selfless Self. In that case his sack holds the whole universe. Nothing is lacking; everything is bearable. The Japanese Zen master Hakuin (1686-1768), also an artist, painted pictures of himself as Hotei, calling them "self-portraits" - in other words, a Selfie.

We have identified two Buddha-level figures: Shakyamuni the founder, and Hotei the traveling monk. To appreciate Hotei's full dimensions, we need to revisit traditional Buddhist cosmology. Mahayana Buddhism, which emerged around the first century AD, ushered in many new buddhas and bodhisattvas (near buddhas). One of these, Maitreya (my-tray-a), was in line to be the Buddha of the next cosmic cycle, billions of years in the future.

Chinese Buddhists revised this scenario, shortening the time of Maitreya's arrival to the near future, if not the here-and-now. Cloth Sack, the tenth-century monk, linked himself to Maitreya in a final poem. Might the future Buddha already be keeping an eye on things, incognito? Was Hotei an avatar? From that time on, if you encountered a wandering monk, you had to wonder.

In China, Hotei/Maitreya became a symbol of hope for a better world. On the serious side, revolts in the name of Maitreya erupted sporadically for centuries. On the lighter side, Hotei metamorphosed into the Laughing Buddha. In Japan, he became a god of good fortune.

What about the belief that rubbing a Buddha's belly brings good luck? Does the belly-touching gesture of Kanō's Hotei allude to that? Ritual rubbing probably has prehistoric roots. Fortunately, it is almost impossible to rub a Buddha the wrong way.

Within Zen, great masters are criticized with surprising severity. Insults such as "blind donkey," "dreg-slurper," or "broken-toothed barbarian" are not uncommon. Even the Buddha doesn't get a pass: one Zen monk famously tossed a wooden Buddha figure into a fire, just to stay warm. It seems un-Buddhist, to say the least.

Sometimes this eye-catching iconoclasm is praise in disguise. But its more important function is to restrain the impulse to glorify religious/spiritual heroes. The Buddha's humanity, Hotei's earthiness, and the Laughing Buddha's availability are reminders that the joy of enlightenment is not beyond the reach of ordinary people.