Note: I wrote the essay below a decade ago and it was collected in "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres." On the occasion of Mother's Day, it is reposted here. My mother suffers from dementia and forgetfulness now, and is growing frail, but her ways remain forever devoted to traditions, to distant memories, to ancestors worshipping and family.

She turns 70 but she remains a vivacious woman -- her hair is still mostly black, there is still a girlish twang in her laughter, and her eyes twinkle at the telling of a joke -- still, mortality weighs heavily on her soul. After the gifts are opened and the cake eaten, Mother whispers to her younger sister-in-law: "Who will light incense to the dead when I'm gone?"

Aunty shakes her head. "Honestly, I don't know. None of my children will do it, and we can forget the grandchildren. They don't even understand what we are doing when we pray to the dead. I guess when we're gone, the ritual ends."

Such is the price for living in America. I myself can't remember the last time I lit incense sticks and talked to my dead ancestors. Having fled so far from Vietnam, I can no longer imagine what to say, or how I should address my prayers, or for that matter what promises I could possibly make to the long departed.

My mother, on the other hand, lives in America the way she would in Vietnam. Every morning in my parents' suburban home north of San Jose, with a pool shimmering in the backyard, she climbs a chair and piously lights a few joss sticks for the ancestral altar, which sits on top of the living room's bookcase. Every morning she talks to ghosts.

She mumbles solemn prayers to the spirits of our dead ancestors, and to the all-compassionate Buddha. What is she asking for? Protection for her children and grandchildren, and that they should prosper in America.

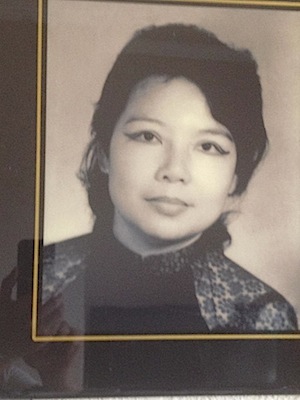

Mother as a young woman in Vietnam

At that far end of the Asian immigrant narrative, however, I will readily admit that I cannot help but feel a certain twinge of guilt and regret upon hearing my mother's question to Aunty. Once upon a time, in that other world, I was a pious child. I paid obeisance to the dead, prayed for good health. As the youngest in my family, it was my task to climb the table over which the altar stood. It was I who placed the incense in the bronze urn nightly.

In America, however, I became rebellious, distant. And once Mother asked me to speak more Vietnamese inside the house. "No," I answered in English, curtly. "What good is it to speak it, Mom? It's not as if I'm going to use it after I move out."

She had this pained look in her eyes. If she was proud of his accomplishments, she mourned the distance that had grown between her and her youngest son. Something in the water, in the airwaves, changed his inner makeup and dulled his Confucian ways. America gave him too much freedom. America made him self-centered, introspective. "He thinks too hard, he reads too much," she complained to Father, who shook his head and smiled.

We have made peace since then, she and I, but it does not mean that I have become a traditional, incense-lighting Vietnamese son. I visit. I take her to lunch. I come home for important dates -- New Year, Thanksgiving, Tet, grandfather's death anniversary.

But these days, in front of the family altar with all those faded photos of the dead staring down at me, I often feel oddly removed, as if staring not at the present, but a relic of my distant past. And when, upon my mother's insistence, I light incense, I do not feel as if I am participating in a living tradition so much as pleasing my traditional mother.

Mother's 80th birthday last year

We live in two different worlds, after all, she and I. Mine is a world of travel and writing and public speaking; hers is a world of consulting the Vietnamese horoscope and eating vegetarian food when the moon is full, of attending Buddhist temple on the day of her parents' death anniversaries, a pious devotion.

But at her birthday party, having listened to her worries, I had to wonder: what will indeed survive, Mother?

I wish I could say that I will pick it up as naturally as any Vietnamese in Vietnam would. I wish I could assure her that, after she is gone, each morning I will light incense for her and all the ancestors' spirits before her, but I can't.

Yet, if some rituals die, some others have only just begun. I am, after all, not a complete American brat, dear mother. Every morning I write, rendering memories into words. I write, going back further, invoking the past precisely because it is irretrievable. I write if only, in the end, to take leave.

And this morning, with the San Francisco fog drifting outside my window, it occurs to me as I type these words that this too, strangely enough, is a kind of ritual, a kind of filial impulse to reconcile Mother's world and my own. The solemnity of the act -- my fingers gliding on the keyboard, my mind on things ethereal -- is something akin, at last, to my mother's morning prayers.

Andrew Lam is editor and cofounder of New America Media, an association of more than three thousand ethnic media outlets in the United States. He is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres, and most recently, a collection of short stories, Birds of Paradise Lost,a collection of stories about Vietnamese refugees struggling to remake their lives in America.