Your child, my father, and all of our loved ones who may be suffering from illnesses are not rats or dogs or monkeys. So why do animal experimenters keep treating them as though they are?

Suppose you are an experimenter and are determining if methylprednisolone, a steroid, will help humans with spinal cord injury. After crushing the spinal cords of many different animals, you test the drug on them. My colleagues and I looked at the published studies (62 in total) and here are the results broken down by species [1]:

- In Cats: the drug was mostly effective

- Dogs: mostly effective

- Rats: mostly ineffective

- Mice: always ineffective

- Monkeys: effective (1 experiment)

- Sheep: ineffective (1 experiment)

- Rabbits: results were split down the middle

Based on these results, can you determine if methylprednisolone will help humans with spinal cord injury?

This leads to the third major reason in my series why animal experimentation is unreliable for understanding human health and disease:

IN REGARDS TO PHYSIOLOGY, ANIMALS AREN'T LITTLE HUMANS

Noticing how methylprednisolone results differed among species, we then examined the reasons behind this [2]. We found that living conditions, stress, and the artificiality of the models affect test results.

Furthermore, test results vary by species and even by strains within a species, because of inter-species and inter-strain differences in neurophysiology and the functions of the relevant genes. For example, the cellular and tissue pathology of spinal cord injury, injury repair mechanisms, and recovery from injury vary greatly between different strains of rats and mice.

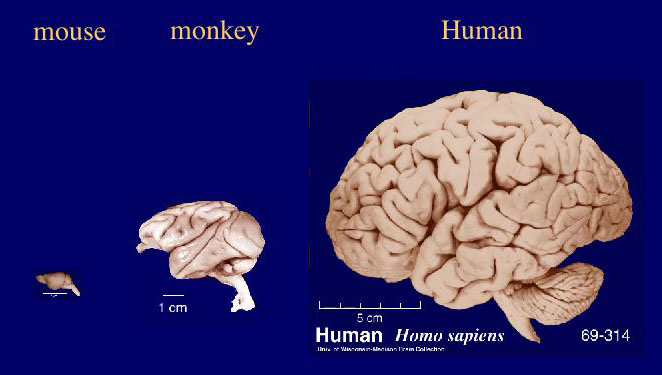

Just as you are not a larger version of a mouse or a monkey, they are not smaller versions of you. This photo may give you some ideas why.

Although we share most of our genes with other mammals, there are critical differences in how our genes actually function. As an analogy, as pianos have the same keys, humans and animals share the same genes. What makes us different? The way the genes or keys are expressed. Play the keys in a certain order and you hear Chopin, a different order and you hear Ray Charles, yet a different order and it's Jerry Lee Lewis. In other words, same keys or genes, but very different outcomes.

To circumvent these differences, experimenters alter animals' genes in attempts to make them more "human-like." Does this work?

How Human Are "Humanized" Mice?

Mice are used extensively because of their supposed genetic similarity with humans and because their entire genome has been mapped. Their genes have been manipulated to make them more "human." However, as we saw in the prior article, if we put a human gene in a mouse, that gene is likely going to function quite differently from how it functions in us. To continue the piano analogy, the key that was playing Chopin is now playing Ray Charles.

Even among mice, corresponding genes can behave very differently. The disruption of a gene in one strain of mice is lethal, whereas disruption of that gene in another strain has no effect [3]. Six strains of mice, which share the same genetic mutation that causes Fragile X syndrome, show radically different behaviors. In other words, one strain of mice isn't predictive of another strain of mice.

These are just a few examples. The more we look, the more we discover that "humanized" animal models aren't living up to their promise. That's because human genes are still in non-human animals.

Are Non-Human Primates Human Enough?

Instead of mice, many experimenters use non-human primates (NHPs), hoping they will mimic human results. Here again, however, the species barrier is real. There is a reason why a monkey looks like a monkey and your wife or husband looks like someone you wanted to marry. Our different outward appearances are a reflection of differences in our internal biology.

Chimpanzees share 98 percent percent of our genes, yet there are many differences between chimpanzees and humans in DNA sequence and how our genes function [4]. These genetic differences ultimately cause differences in physiology.

HIV/AIDS vaccine research using NHPs is one of the most notable failures in animal experimentation. A lot of time, energy and money have been spent studying HIV in chimpanzees and other NHPs. Yet all of about 90 animal-tested HIV vaccines failed in humans [5].

Remember when hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was hailed for preventing heart disease and strokes? The campaign to prescribe HRT in millions of women was based in large part on experiments on non-human primates. HRT is now known to increase the risk of these diseases in women [6].

Experiments using monkeys are not any more predictive of human responses than those using any other animal. This is the essential problem with using other species to inform human health.

No two humans are alike in their physiology. Even identical twins differ in their susceptibility to diseases and their responses to medications. If we can't reliably extrapolate from one identical twin to another, how can we expect to extrapolate results from different species to humans?

Let's return to methylprednisolone. Do we pool results from all tested species? If we do, our answer on the usefulness of the drug may depend on whether most of the experiments involved rats and mice, which showed the drug to be largely ineffective, or cats and dogs, which showed the opposite.

If instead we put our faith in results from only species we believe to be most predictive of human responses, how do we know which species to choose? Monkeys or rats? But it doesn't stop there -- do we trust the results from a certain strain of rat and not another strain?

So what's the final answer? We don't know. Besides being incredibly cruel and wasteful, the animal experiments are completely useless in determining if methylprednisolone is effective in humans. Rather frustrating, isn't it? That's the point.

Stay tuned for my next article: The top 3 ways that animal experimentation hurts humans. Share your thoughts. What do you think they are?

Want to know more? Check out my website and join me on Facebook.

- Akhtar, et al. ATLA 2009; 37:43-62.

- Akhtar, et al. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2008; 19: 47-60.

- Horrobin. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2003; 2: 151-154.

- Akhtar (2012) Animals and public health. Why treating animals better is critical to human welfare. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 148.

- Bailey. ATLA 2008; 36:381-428.

- Pippin. South Texas Law Review 2013; 54: 469-511.