Women are 53% of voters and 18% of Congress

A majority (58%) of Americans would like to see men and women represented equally in the U.S. Congress, according to a new HuffPost/YouGov poll. Despite efforts like Rutgers University CAWP 2012 Project "20% in 2012" campaign, women still account for only 18% of Congress.

While many would like to see women members of Congress at parity with men, many challenges remain to getting them even close. For Republican women, the challenges are even steeper.

Where there's no will, there's no way: First, women have to want to run and most don't. Studies show that men are significantly more likely to think about running for office than women - a gap that shows no signs of closing. For example, American University researchers conducted a Citizen Political Ambition Study in 2001 and again in 2011 and in both studies, despite a ten year separation, men were 16% more likely than women to consider running for office. Women expressed much more distaste for the trappings of a political career - negative campaigning, loss of privacy, less family time. While men saw politics as a career ambition, women were more likely to come at it through a cause or issue on which they may have spent decades working in their communities or volunteer organizations before thinking about politics. And even then, women need to be encouraged to seek political office.

The younger generation of women is ambitious, just not politically: The gender gap in political interest continues with the Millennial generation. A recent study "Girls Just Wanna Not Run" by American University Professor Jennifer Lawless and Loyola Marymount University Professor Richard Fox (who pair up for really interesting gender and politics work) found that college women are just as ambitious as college men when it comes to wanting to have a successful career and make a lot of money, but they were significantly less likely to see politics as one of their paths. College women were far more likely (63%) than college men (43%) to say they had never even thought about running for office when they're older. They were also less likely to think they would even be qualified. In terms of making a difference in their community or country, college men were more likely to say that running for office would be the way to achieve it, while college women were most likely to say that working for a charity could best bring about change.

The study's researchers wondered if high school seniors might be different so we conducted a small, nonscientific, Facebook survey of our intern Kristen's peers at T.C. Williams High School in Alexandria, Virginia and found these young college bound women described themselves as capable (80%), caring (73%), smart (73%), and ambitious (67%). But only 20% said "interested in politics" would describe them very well. (We hope to have time and money to follow up with a representative survey.)

Juggling motherhood and politics isn't easy: The American University Citizen Political Ambition Study found no difference in political ambition between mothers with kids at home and those without kids at home, but their sample was among professionals who already decided to pursue careers in law, business and other demanding fields. It did not include women who may possess the credentials and advanced degrees but decided to stay home or direct their energy to a home based business while raising kids. In fact, a 2009 Center for American Women and Politics survey of state legislators found that women state representatives were less likely (14%) to have kids under 18 than male state representatives (22%) and that having children that were old enough was a more significant factor for women (57%) than men (42%) in deciding whether to run.

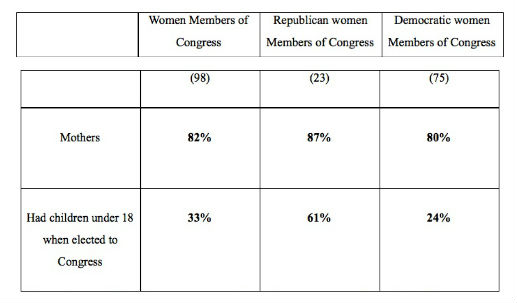

We weren't able to find statistics on how many current women in Congress were elected when they had kids at home, so we gathered the data ourselves. We found that 82% of women members of Congress are mothers, but that most Democratic women had either grown kids or no kids when first elected to Congress, while the majority of Republican women serving in Congress had kids under 18 when first elected.

This small group of Republican women members of Congress are survivors. Most of them ran for office while balancing the responsibilities of younger children and, to top it off, faced extra resistance from within their own party to get there.

Republican women have a particularly tough road: In 2012, 57% of Republican women who ran for a U.S. Senate or U.S. House seat lost their primary. Democratic women were more numerous to start with (210 Democratic women filed compared with 124 Republican women) and more successful getting out of their primaries - only 38% lost. In 2010, 64% of GOP women lost their primaries, compared with just 34% of Democratic women (source: CAWP).

A 2008 Pew Research survey examined the impact of gender and parenthood on support for a U.S. congressional candidate, testing hypothetical candidates "Ann" and "Andrew" with and without school age kids. The bottom line was that Republicans were far more likely to support Andrew the dad than Ann the mom. Women candidates with children at home were the most appealing of the options to Democrats, but not Republicans. The Pew report concluded that "women with young children pay a 'mommy penalty' among Republicans if they run for Congress."

And to show how little has changed; twenty years ago I conducted similar research for the now defunct Republican Network to Elect Women to test the impact of a Republican candidate's gender on voter support. On a national survey, we split sampled identical bios, changing only the gender:

"I am going to read you a brief description of a potential candidate for Congress. After I read this, I will ask you to evaluate [him/her]. The candidate is a Republican [man/woman] who has never run for office before, but has been active in the community. [She/He] is a businessperson who is running because [he/she] says that Congress"just doesn't get it" and wants to bring a commonsense business approach to government. [His/Her] first priority is to work to reduce government spending and waste."

The female Republican candidate got 13% less support from GOP men and 10% less support from GOP women. We also tested attributes and found that the Republican woman candidate was less likely to be seen by her own party's voters as a strong leader, qualified and, most importantly, conservative. The assessment, especially by the most conservative voters, that the woman was more moderate or liberal, had a lot of impact on their vote behavior.

Harvard Professor David King, who dissected and analyzed our data in an interesting paper writes that "Given that strong party identifiers are the most active slice of voters in primaries, our experimental data suggest that female Republicans will have a more difficult time getting nominated." One could argue that since 1993, the Republican primary electorate has gotten even more narrow, conservative and male.

Why bring up data that's 20 years old? Well, the just released HuffPost/YouGov poll asked, "If you could choose, would you rather see the U.S. Congress made up mostly of men, mostly of women, or about the same number of men and women?" A majority of everyone - except for Republican men - thought an equal number of men and women sounded good. Republican men were far more likely than anyone else to think Congress should be mostly men. They also thought that women's interests were already fairly represented in Congress...so why bother electing women? So, it seems, the more things change, the more things stay the same.