Though it produced a body of work kaleidoscopic in its variety and intersecting interests, the search for answers to deceptively simple questions drove Alan Lomax to wander America and eventually the world: "Why do people sing? Why do they dance?"

A new Lomax biography follows his journey as he emerges from the shadow of his father, folklorist John Lomax, through successive and more expansive expeditions to collect folkloric traditions, to the unified theory of human creative expression that his collection of audio, film, photographs, and video made possible. In Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded The World (Viking), John Szwed makes a powerful argument for Lomax as "one of the most influential Americans of the twentieth century, a man who changed not only how everyone listened to music but even how they viewed America."

Lomax's later, more advanced ideas about the world's music and dance traditions, a methodology he called Cantometrics and Choreometrics, may yet exert similar influence on the current century. Not well understood, even by academics who have largely abandoned the comparative approach Lomax championed, his theories remain fertile ground for further exploration. But it was Lomax's early adventures as he discovered and recorded music, dance and folklore that drive the life story. Those journeys brought him in contact with performers who became inseparable from our idea of "folk music": Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Leadbelly, Burl Ives, Jelly Roll Morton, Josh White, Sonny Terry, Muddy Waters, Bob Dylan. Through an indefatigable production of concerts, festivals, recordings, books and radio shows, Lomax himself became inseparable from the folk revival that his work helped spark. (Lomax's Southern Journeys of 1959 - 60 are the subject of recent releases by the Lomax Archive's Global Jukebox label.)

His pursuit of song led far afield: from 1930s (on occasion working with Zora Neale Hurston) expeditions to the Caribbean and Haiti (the collected and remastered Haiti recordings earned two Grammy nominations), to his European tours of the 1950s, Lomax collected and presented the world's varied cultural traditions, in some cases just before they vanished forever. As a result of his advocacy and preservation, Lomax influenced the folk revivals of the 40s and early 50s, the folk boom of the late 50s and early 60s, what we now call world music, and jazz. In every aspect of his life's work there is an animating principle: all local and indigenous expressive traditions should be valued equally as evidence of our adaptation to life on Earth.

Anthropologist and folklorist John Szwed, currently a professor of music and jazz at Columbia (and Grammy winner for his notes to the Lomax recordings of Jelly Roll Morton), is uniquely qualified to present the story. Szwed had personal and professional exposure to Lomax, working alongside him occasionally from the 60s. (Disclosure: I periodically work with the Lomax Archive's Association for Cultural Equity on online features and content). Weaving a portrait of Lomax's life and work offers many threads. I asked Szwed about what work Lomax felt was his most important: "I believe he thought his theories of the meaning of dance and music, Cantometrics, Choreometrics, and the other methods he developed for comparative studies of music, dance and speech around the world were his most important. Still, all his work is of importance, and the early work made the later possible. No one, it's worth noting, has done so much work in folklore and ethnomusicology, and no one has seriously taken up the big questions he asked: such as 'Why do people sing?' His advocacy for folk artists was very important, but this work was also made possible by his tireless and inspired collecting and the massive archives of recordings and film that he built first."

Lomax employed successive generations of technology, from the first decades of electric media (for example, he cut aluminum discs to record in Haiti in 1936) to digital video and interactive discs; his archive now lives on the internet as well as the Library of Congress. "He certainly thought everyone's music and dance deserved the best documentation possible," Szwed says. "He wanted to give their arts the tools to allow them to compete with the highest arts. The computer and the web are extensions of his own comparativist impulse, tools of his trade." The documentary impulse anticipates what we now call oral history: "The emphasis on gathering authentic voices (the documentation he did with Jelly Roll Morton, Woody Guthrie, Vera Hall, et al.) was inspired by the early-20th century Russian documentation of folk performers and their histories, and the 'life histories' that anthropologists were doing among American Indians and ex-slaves in the US at the time. But he was likely the first person to use a recording machine to accomplish this."

Driven, certain of his work's importance and value (his FBI file describes him as "very temperamental and ornery"), Lomax was challenging to colleagues and companions. Szwed describes Lomax's pursuits as often "lonely," acknowledging that "few men or women could stand up to the rigor and energy that the work took." His refusal to disavow the populist, progressive aspects of his work also led to periodic surveillance. "He never realized the extent of his surveillance," Szwed maintains, "and, when he became aware of it from time to time, thought of it as just one or another repressive regime at work. None of it stopped him." And controversy finds anyone who pursues a singular path in the public eye. A relatively privileged white man working, no matter how idealistically, in the culture of rural, poor and ethnic societies will be scrutinized for exploitation. Szwed acknowledges the claims. "My way of writing bios - and it's for sure not the typical way -- is to let the subject speak as much as is possible," he responds. "I also try to let the subjects' critics be heard the same way. I avoid speculating or guessing about what I don't know for certain. But the four subjects I've written about (Sun Ra, Miles Davis, Jelly Roll Morton, and Lomax) were already weighted down with false claims made against them, and that was one of the reasons I found them interesting. Yet this has put me in the position of having to correct the information where I can. So I've sometimes been accused of being uncritical and too kind to the subjects. But with people who have been misrepresented, I'm happy to run that risk to correct the record."

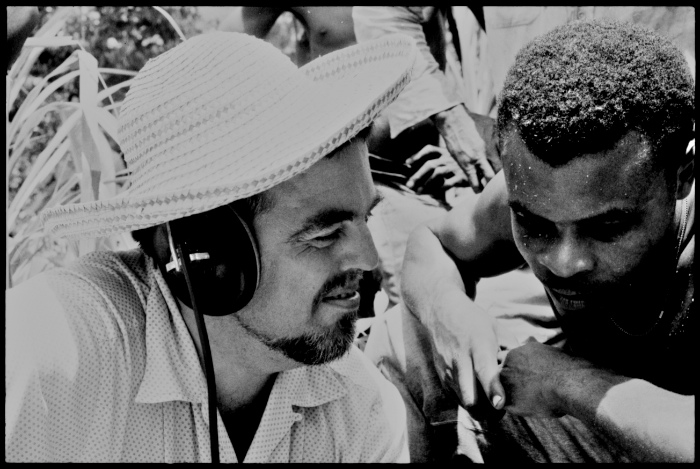

Photos: Alan Lomax in Domenica, 1962, courtesy Association for Cultural Equity; John Szwed by Martha Rose