In an effort to keep migrants from entering Britain through Channel Tunnel trains, the British government has recently decided to increase security around the train line at Coquelles and in the French town of Calais on the other side of the channel by building fences. Such a reaction is expected, since physical barriers are one of the most popular ways of controlling migration flows around the world.

Yet, fences create rather contradictory scenarios in immigration policy: while they may deter migrants from entering a country from one particular point, they create new pressures elsewhere; they encourage the proliferation of the same smuggling and human trafficking networks European governments strive to dismantle through programs like the recently re-launched anti-smuggling operation in the Mediterranean; and finally, physical barriers force migrants into life-threatening situations, such as crossing the Mediterranean, to which European governments then try to answer through rescue operations like Mare Nostrum. As such, fences are the least effective and least humane tool of immigration policy. The following case studies illustrate why more precisely.

Ceuta and Melilla: The two Spanish enclaves in Morocco are unique in that they are Spanish land; thus although they are found inside a North African country, they are part of the European Union. Despite the fact that they are surrounded by three rows of six-meter high barbed-wire fences, many immigrants are not deterred from trying to enter these territories; they either attempt to make it over these fences, in which case most are caught and sent back, heavily injured, or sometimes killed, or they take to sea, where many often drown. The two areas have been flagged by human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, both for the inhumane physical treatment of immigrants who are attempting to cross into the two territories and for the Spanish government's violation of the principle of non-refoulement (no forced return) by turning away migrants before they can make their asylum claims.

Bulgaria: In September 2014, Bulgaria completed a 21-mile border fence along its border with Turkey, in order to prevent "the illegal crossing of the border" and to "transfer such attempts to the border check points as it is done in every other country," according to Defense Minister Angel Naidenov. Along with this new barrier, the Bulgarian government has also deployed additional border officers and begun to use new surveillance equipment. As usual, these efforts are a response to an increase of immigrants, mainly Syrian refugees, trying to enter Bulgaria. Like in Ceuta and Melilla, such measures by the Bulgarian government have involved violations of human rights and international law; in an April report, Human Rights Watch wrote about asylum seekers being forced back into Turkey, another violation of non-refoulement, and about Bulgaria's failure to provide basic humanitarian assistance. Spokesman for UNHCR in Bulgaria Boris Cheshirkov argued, "UNHCR in principle is against deterrents such as fences as they do not provide a solution, but provide pressures elsewhere. Mothers, fathers, and children fleeing war and persecution should be allowed onto the territory of Bulgaria."

Hungary: While 43,000 migrants registered in Hungary in 2014, more than 80,000 registered by July of this year. Such an increase in immigration has caused outrage in Hungary, and a four-meter high, 175 km fence along its border with Serbia is to be completed by November 2015. Amnesty International France has warned against recent legislation which prevents asylum seekers who pass through countries considered "safe" by the Hungarian government from applying for asylum in Hungary and allows for their expulsion. According to Amnesty, such a law disregards each state's obligation to protect refugees by allowing them to apply for asylum, especially since it would expel refugees to countries like Serbia and Macedonia, which do not have functional asylum systems.

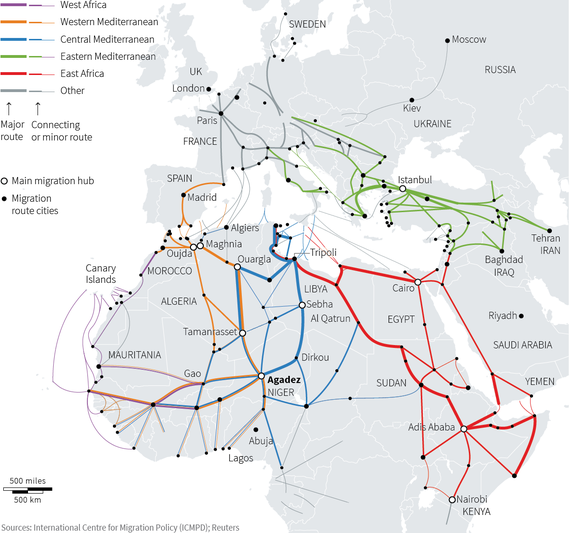

These examples highlight that physical barriers are usually accompanied by anti-immigrant legislation, and they also show that fences do little to mitigate migration; rather, they divert migrants elsewhere and thus simply change migration patters. For instance, when security was increased along the Greek border with Turkey (including a fence) in 2012, migrants began going towards Bulgaria. As the example above describes, increased immigration to Bulgaria led the country's government to increase security along its own border and again divert refugees elsewhere. Gil Arias Fernandex, deputy director of Frontex, explains that such measures did not mean that refugees were not reaching Europe - "those thousands who failed to cross into Bulgaria were offset by larger numbers crossing from Turkey by sea to the nearby Greek islands." And yet, such a situation raises the question: how long can governments redirect migrants from one country to another, and what will be the ultimate effects of such confining policies?

Migration patterns constantly evolve and multiply in response to various factors, including increased border security.

If physical barriers like fences are so ineffective and inhumane, why are they so popular? As Ruben Anderson, anthropologist at LSE's Civil Society and Human Security Research Unit, argues, fences are an easy way for politicians to react to discontent regarding immigration. When questioned about what they are doing to keep "illegal immigrants" from entering the country, they can easily point to a fence to demonstrate their commitment to securing the nation's borders. Especially when viewed in the context of the rise of many extreme right-wing parties in Europe, it is no surprise that fences continue to pop up.

Furthermore, as Anderson argues, fences allow governments to crystallize the immigrant threat by creating a space where "masses of immigrants" gather and "siege" the host country. If terms such as "floods" and "influxes" of immigrants permeate the news, fences are where these floods and influxes materialize and can be used by the media to show the extent of the country's immigrant crisis. In effect, fences serve as political tools to justify human rights violations and inhumane treatment of migrants.

This summer is not the first time that Calais and the Channel have made headlines regarding immigration. Rather than working together to erect another physical barrier, the British and French governments should question how root causes of migration can be addressed and work within the bounds of international law to make sure no agreements regarding asylum or human rights are violated. Another fence in Europe will do little to stem immigration flows, and it's time migration is seen not as a nuisance, but as a signal of larger problems in those parts of the world thousands are fleeing.