During oral argument in the Proposition 8 case last month, Justice Anthony Kennedy said:

I think there's... substance to the point that sociological information [about gay marriage] is new. Five years of information to weigh against 2,000 years of history or more...[O]n the other hand, there is an immediate legal injury (or... what could be a legal injury), and that's the voice of these children. 40,000 children in California, according to [a brief in the case], that live with same-sex parents, and they want their parents to have full recognition and full status. The voice of those children is important in this case, don't you think?

To a lot of people, it may seem downright strange that a Supreme Court justice is asking how social scientists would project the impact of their potential ruling. As a social scientist myself, I find this an interesting phenomenon, of which there is quite a history.

During the Industrial Revolution of the late 19th/early 20th century, state governments (and Congress) became more active in regulating the economy, particularly employer-employee relations. In many instances, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down these laws as a violation of the right of both employees and employers to make economic contracts as they see fit.

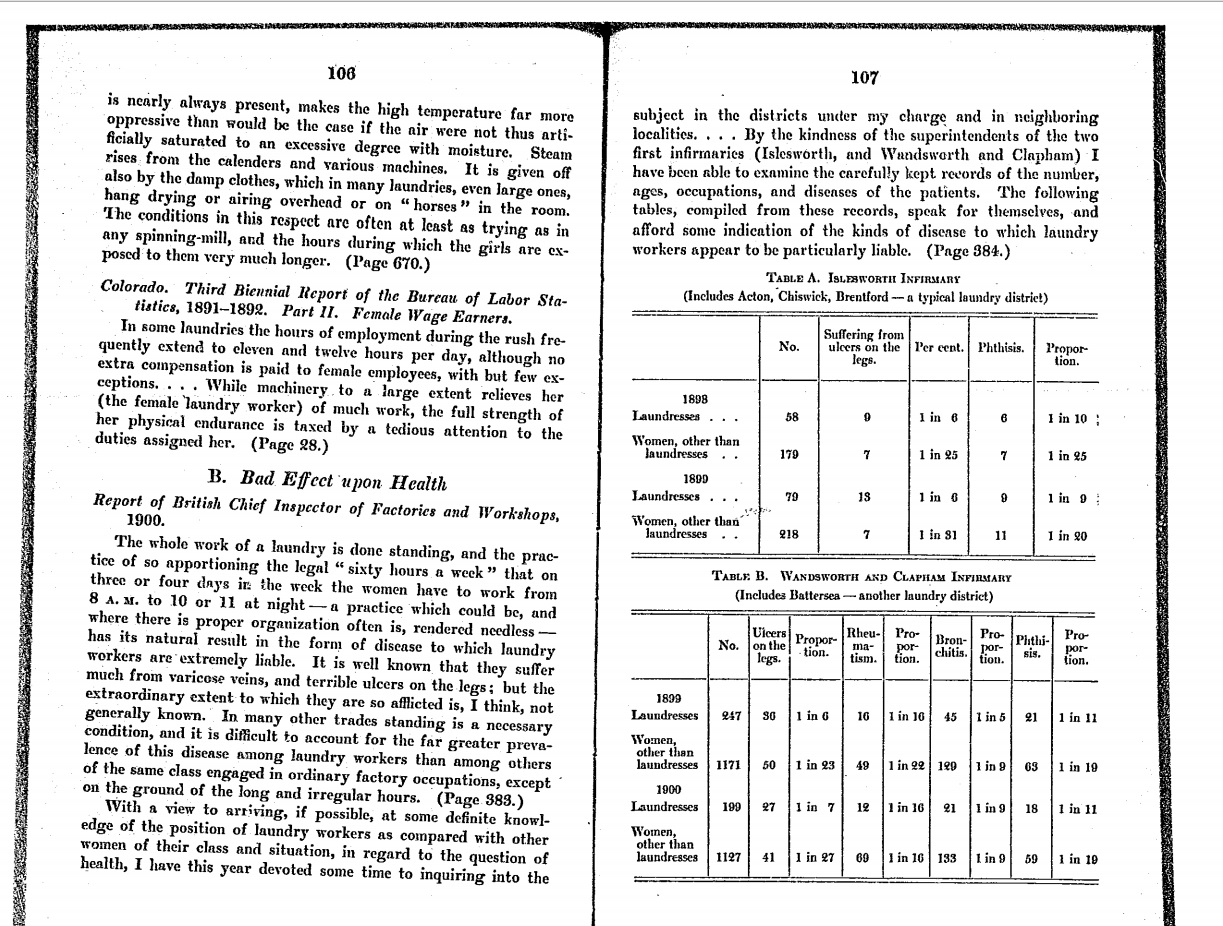

State governments would often defend these types of laws -- the rights to join a union, maximum work hour laws, minimum wage laws, etc. -- on the grounds that they protected the health and safety of workers. In defending a law regulating the number of hours per day that women could work laundries, future Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis issued a lengthy appendix to his brief detailing the potential hazardous health effects that the Oregon law was attempting to mitigate (as well as highlighting the fragility of women in demeaning terms).

The most famous (or to some legal scholars, infamous) invocation of social science evidence in Supreme Court history was in Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 case which declared school segregation unconstitutional. In prior cases, the Court had chipped away at the doctrine of "separate, but equal" by striking down segregated law schools and graduate schools where the programs for black students could not be considered materially equal to those of whites.

In order for desegregation to work across the board, the Court needed to argue that separate schools were inherently unequal, even if given identical levels of resources. To make that argument, Chief Justice Earl Warren cited several psychology and sociology studies that presented evidence that segregation, in its many forms, created:

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this finding is amply supported by modern authority.^11

Footnote 11. K.B. Clark, Effect of Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality Development (Mid-century White House Conference on Children and Youth, 1950); Witmer and Kotinsky, Personality in the Making (1952), c. VI; Deutscher and Chein, The Psychological Effects of Enforced Segregation A Survey of Social Science Opinion, 26 J.Psychol. 259 (1948); Chein, What are the Psychological Effects of Segregation Under Conditions of Equal Facilities?, 3 Int.J.Opinion and Attitude Res. 229 (1949); Brameld, Educational Costs, in Discrimination and National Welfare (MacIver, ed., 1949), 44-48; Frazier, The Negro in the United States (1949), 674-681. And see generally Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944).

While law professor Michael Heise welcomes the Footnote 11 approach as indicative of the multifaceted and multidisciplinary effect law exerts in our society, it is also important to remember that social science can cut both ways. In prior research, I examined a Kentucky law segregating school -- even private schools, such as Berea College, which wanted to be racially integrated. I described the state's legal argument as:

strikingly similar in its philosophical and legal basis to the famous "Brandeis Brief" submitted to the Court in Muller v. Oregon in that same year. Just as the "Brandeis Brief" disparaged the physical and social potential of women, Kentucky based its arguments on the fundamental inferiority of the African American race. The logical conclusion of this inequality was that the races must be kept separate to prevent racial amalgamation.

To prove its contention of natural and eternal racial differences, Kentucky cited an array of scientific evidence, which Benno Schmidt characterizes as "eugenic pseudoscience" used for an "unabashed exaltation of racism." At the forefront was a study by Dr. Sanford B. Hunt, a prominent expert in anthropometrics -- the study of the physical characteristics of racial groups. Hunt's analysis of brain weight indicated that an average African American's brain weighed five ounces less than the brain of an average white person. The brain of an average mulatto weighed even less than the brain of an average African American. In a shocking display of racism, Kentucky argued that this physical difference is "not the result of education, but is innate and God-given; and therein lies the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon-Caucasian race."

The Supreme Court refused to strike down this law.

How will social science influence the Court in the gay marriage cases? The American Sociological Association submitted an amicus curiae (or "friend of the Court") brief outlining the scientific consensus that children raised by same-sex parents "fare just as well as children of opposite-sex parents." Based on the precedent set by Footnote 11, social science may be a critical factor in this case.