Recently, PBS's Frontline aired a disturbing documentary chronicling the National Football League's history of downplaying and distorting the evidence that football-related head injuries cause long-term brain damage. The film included footage from a 2009 Congressional hearing in which lawmakers compared the NFL's approach to the problem to Big Tobacco's decades of sham science and lies about the link between smoking and disease. The analogy is spot on.

The NFL borrowed a page from Big Tobacco's playbook by choosing to dump millions of dollars into experiments on animals that won't ever help humans, but will allow dangerous activity to continue while giving the public the illusion that they're being protected.

Inconclusive tobacco studies on animals allowed cigarette companies to peddle their products despite mounting evidence that smoking causes human disease. This is now happening with head injury experiments. In one 2009 experiment that was co-authored by a member of the NFL's Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee, rats were smashed in the head with a projectile. The animals suffered from brain hemorrhaging and other brain injuries. Some of the animals died immediately on impact as a result of bleeding in the brain.

Yet, the authors paradoxically conclude that, "When the immunohistochemical results are extrapolated to professional football players, concussions result in no or minimal brain injury." Another experiment by the same team concluded that similar animal head injury experiments indicated that "NFL concussions may involve minor petechiae that are absorbed within days but are below the level of transition to more serious brain injury."

The authors added that, "There are known anatomic differences in the brains [between humans and rats], and the reliance of a single scale factor based on the radius of the brain can be questioned" and that "the scaling used [to extrapolate results from rats to humans] has no known validation for brain injury research of this type."

In other words: Because it is widely acknowledged that animal experiments do not translate to humans -- which I have discussed previously -- it's easy for the NFL researcher and his colleagues first to waste resources and animal lives by conducting meaningless experiments and then to manipulate the findings from rats to support the league's claim that concussions do not cause long-term brain injuries.

The NFL continues to fund misleading head injury studies on animals (see here, here and here, for example) that will not get the league closer to identifying the precise causes of brain trauma in football players and how to prevent and treat it.

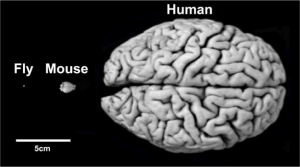

Despite some similarities, the brains of humans and other animals are vastly different in important ways. For example, the human brain weighs 675 times more than a rat's brain and 3000 times more than a mouse's brain. There are 86 billion neurons in the human brain; in the mouse that number is only 70 million. The cerebral cortex (the outermost layer of the brain) makes up more than two-thirds of the human central nervous system and less than one-third in rats. Our skull shapes, thickness, and sizes are distinct, which greatly affect what kind of brain damage we sustain.

Each of these and numerous other differences in neuroanatomy and function -- and the unique nature of the injuries being studied -- make brain experiments on other animals irrelevant to humans. The International Brain Injury Association states that "animal models of [traumatic brain injury (TBI)] cannot possibly capture the diversity of the human physical injury after TBI." For example, hitting sedated animals in the head is nothing like what happens to a moving football player -- often with a history of head injuries -- when he is being hit with various amounts of force from different directions by several 300 pound defensemen.

Further, neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's Disease and ALS usually take decades to develop. One cannot recreate these uniquely human diseases in experiments that last a few weeks or months with animals who don't naturally develop these diseases and whose life spans are only a couple of years.

So of course the animal findings are frequently inconsistent with what occurs in humans. Many of the experiments on animals show no evidence of accumulation of tau protein in the brain, which is a hallmark of human Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), or changes in the white matter parts of the brain and loss of brain volume as occurs in humans.

In order to be effective, experiments have to recreate the injury characteristics, genetic and physiologic changes, and show the same clinical signs as human cases. Animal experiments can't. The NFL-funded experiments themselves prove how irrelevant they are.

Ultimately, the proof of the value of these experiments lies in whether or not their results apply to humans and lead to effective therapies. In this, the animal experiments fail miserably. Despite decades of animal head injury experiments, there is not a single effective treatment for TBI. A British Medical Journal review showed how a steroid treatment was found effective in animal brain injury experiments, but was ineffective in humans and is actually associated with increased human deaths.

The bottom line is that because of inherent species differences and the unique nature of football-related head injuries, animal head injury experiments add more confusion and more layers of complexity. The human brain is hard enough to figure out without throwing in useless, confounding data from other animals.

Rather than wasting brain power, time and money on dead-end animal experiments, the NFL needs to support a more robust "human brain injury project" in which post-mortem brain examination, as well as imaging studies and tissue biomarker studies with living players are coordinated so that we develop a comprehensive picture and model of human brain injury. Only then can we find ways to prevent and cure the repercussions of head injury on the football field and beyond.

Want to know more? Check out my website and join me on Facebook.