If you've been following my historical view of Muhammad Ali, you've learned about his rise to prominence, his religious and political awakening and his repudiation by the boxing establishment and mainstream American culture. But in the rapidly changing climate of 1968, some things began to shift back in Ali's direction...

You may access the other parts of this piece, as well as my other articles here.

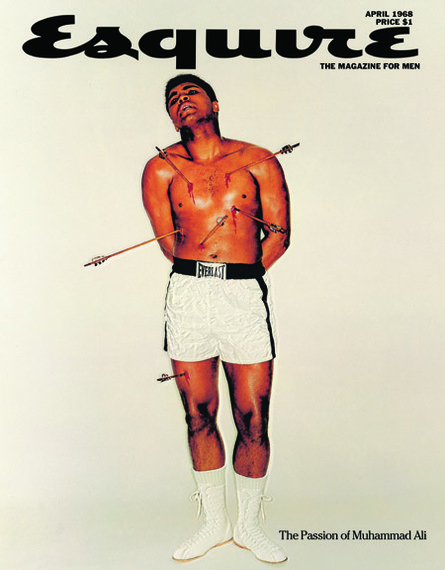

Ali became particularly exciting to the liberal elites, the sort of risque guest that famed composer Leonard Bernstein would invite to one of his radical and bizarre parties. In 1968, the designer George Lois, a photographer for Esquire Magazine, then a cutting edge left-leaning publication, brought Muhammad Ali to his studio for a shoot. The instantly famous image that Lois captured of Ali shot with arrows, as St. Sebastian is portrayed, would not only grace the cover of the April 1968 edition of Esquire, but also become an anti-war poster. Lois's intention was to depict the exiled heavyweight champion as a martyr, like St. Sebastian who was killed for his commitment to Christ by Roman soldiers. Lois saw parallels in Ali, a man who desired to live by the virtue of his faith and was persecuted for it.

In late 1970, the Georgia state boxing commission granted Ali a permit to fight in Atlanta after nearly three years out of the ring. The charge to bring Ali back was led by Georgia state senator Leroy Johnson, who represented a district with a heavy African-American population. There was a fair deal of outcry in the conservative state of Georgia. Governor Lester Maddox bemoaned: "I have called for a day of mourning because of this, that this tragic thing is happening in this United States of America where men have fought so long and their wives and children have sacrificed so much." Maddox's hope of an Ali defeat by knockout would not be realized, as the former heavyweight champion defeated Jerry Quarry in the third round by way of a technical knockout on October 26, 1970.

Even though Ali's appeal failed in 1968, the legal battle was far from over as he and his lawyers tried to bring the case to the Supreme Court. A little over two months later, on January 11th, 1971, the Supreme Court agreed to hear his case, on a 5-3 vote. They decided to review at the request of Justice William Joseph Brennan and against the wishes of Chief Justice Warren Burger. Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American Justice, recused himself from the Clay v. United States case because he was aligned with the NAACP, and disagreed with the the Black Muslims' anti-integration stance. From the start, the court was very much against the boxer, particularly Burger who was in constant communication with conservative President Richard Nixon. The court for the most part viewed the Black Muslims with suspicion. The case was named Clay v. United States not Ali v. United States, a testament to the lack of acknowledgement of Ali's preferred identity. The judges voted 5-3 to uphold the guilty conviction. Chief Justice Berger assigned Justice John Harlan, who had upheld the conviction as well, to write the majority opinion.

While all the legal complexities were being worked out, Ali finally received his opportunity to reclaim his heavyweight title against Joe Frazier; the press deemed the contest "The Fight of the Century". And on March 8, 1971 at Madison Square Garden in New York City, Ali, for the first time in his career, was defeated by decision after fifteen rounds. President Nixon, the symbol of conservative White America, after hearing the news that Ali had been defeated, was described by the White House Chief of Staff as ecstatically jumping up and down cheering the defeat of "that draft-dodger asshole". But in his next fight in the legal arena, Ali would walk away successful, and Nixon would be left enraged.

While Justice Harlan was writing the opinion, his clerk had him read both Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad's books. From this Harlan deduced that Ali would not fight in any war that was not a holy war, the same principle that allowed Jehovah's Witnesses to declare as conscientious objectors. Harlan reversed his decision and the rest of the court followed, voting unanimously to overturn Muhammad Ali's conviction. Ali won the greatest fight of his life. When the decision was handed down on June 28, 1971, there was widespread shock. Ali himself had expected he would go to jail, saying after the news of his vindication: "It's like a man's been in chains all his life and suddenly the chains are taken off." Just like when he refused his induction, there were many who supported the decision and many who condemned it. For example, two Southern newspapers, the Tuscaloosa News and the Southern Missourian, which had both been covering the draft refusal and Clay v. United States, did not report the overturning of Ali's conviction, even though the day before, the Tuscaloosa News had published a brief piece that stated the conviction would be released the next day. Many other newspapers continued to refer to him as Clay for years to come. Ali's image was irreparably damaged to some, but to the boxer, his legal battle was entirely worth the consequences.

You may access the other parts of this piece, as well as my other articles here.