No it's not a printing error. ILLUMInations is the title of the 54th Venice Biennale, which opens June 4 and runs through November 27. The mixing of the upper and lower casing is word play referencing not just the role that Venice, City of Lights, plays in illuminating the art of the world's nations every two years. It's also meant to mitigate a growing criticism of the world's favorite and most ostentatious gathering of the art tribes. In 2011, under the watchful eye of the Art Chief Curator, Bice Curiger, the assembled national pavilions have grown to 84 in number, with 89 national participations, the largest representation of nations yet assembled. It's an international event that heightens the import of Venice's other nickname, the City of Bridges.

But while the Biennale's ever-expanding representation of the world's cultural diversity is something to be lauded, critics and theorists have for years denounced the Biennale's 19th-century proclivity for dividing up the representation of artists by national identity. Surprisingly, it's a tradition that the eminently progressive Curiger has not just carried on, but has gone on record more than once defending.

The debate centers around the issue of cross-culturalism. With the nomadic idealization of art seen today as transcending boundaries (an idea that began circulating in the early 1990s and spread like wildfire over the last decade), many critics see the pavilions as ratifying an anachronistic system of ethnocentrism and nationalism that thrusts enforced identity onto artists who are ideologically removed from or opposed to such geopolitical categorizations of art. History supports the distrust of the pavillion's critics. Particularly the history of the modern museum, the development of the modern art collection, and art criticism as a whole grew out of the authoritarian and colonialist impetus of the 18th- and 19th-century European monarchies and empires. It was after all, an epoch in which art was encouraged to proselytize the regime in power and authoritarianism in general--to the extent that art criticism was implicitly developed to prevent the authoritarian ambitions of the artist from challenging the seats of European power. And who can forget how Mussolini and Hitler used the 1934 Venice Biennale as a backdrop--a pioneering photo op that the fascists excelled at developing--to show the world their solidarity in the spread of German and Italian Nationalism.

Some two centuries later, however, the powerful currents of cross-culturalism that we witness sweeping today's global art markets make it apparent that nationalism has little hold over the artists making a significant impact on them. Then, too, many of the Venice Biennale's pavilion curators have invited a transnational selection of artists to collaborate in their pavilions. With the crosscultural currents mixing up national representation so resoundingly, why would Curiger continue to extend the nationalist selection process by overseeing such first-time pavilion participants as India, Andorra, Bangladesh, Saudia Arabia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and the return of Iraq after a 35 year absence? I know for a fact that Curiger is more ideologically inclined to remove the boundaries confining artists. She did, after all, publish my call for a globally nomadic movement in art-making, marketing and criticism in her art journal PARKETT as early as 1994*, a gesture that to my mind makes her one of the pioneers of crossculturalism in the art publishing industry. It's also a move that would have left me puzzled and alienated by her retreat to the seemingly conservative defense of the Venice Biennale's national pavilions had I not recognized that Curiger's defense signifies a shift underway in the world's increasingly diversified art markets.

After decades of anti-Western posturing, the nations colonized for centuries by European powers can today rejoin their former colonizers, this time transacting freely if not dictating the terms of cultural trade for themselves. It's a new world dynamic that compels us to question whether we aren't rushing the nomadic ideal for an "artworld without borders" by at least a few decades. In stepping back to consider the reclamation of cultural, even national identity and history by the world's former colonies, we can see that there is still much to be gained by exhibiting artists under a national identity. That doesn't mean that nationalist agendas in art no longer pose a danger to cross-culturalization. Nationalism can still and at any time turn into jingoism and ethnic prejudice. What has changed, however, is the greater proliferation of indigenous cultural production and collection that suggests the reinforcement of indigenous cultural identity also benefits the diversity of cultures internationally.

In recent years a new breed of art collector and art institution has emerged in the growing global agora of art as capital has flowed increasingly from the old economic centers of Europe and North America to such economies as India, China, Latin America, and Africa. Alongside the culturophile who for decades has been ideologically nourished by cultural cross-fertilization have come the collectors and institutions who have worked to revive indigenous interest in traditional and national artists where previously there had been little or none. Trends at the new galleries and auction houses that have sprung up around the world indicate that buyers indigenous to the new art markets have become so eager to see representation of their national or tribal art gain in esteem and value internationally that they generate an economic windfall that in many instances proves resistant to the volatile fluctuations in the global economy since 2008. A recent study of the global art markets show that despite the ensuing recession, the steady incline in value and appeal of world art as a new "gold standard" proves idealism and aesthetic appreciation can and will fuel art markets.

The fact is the new collectors and institutions of former colonies are buying up the art of a national, cultural and tribal character indigenous to their homelands, much of which had depreciated for decades during the Western monopolization of markets. With the flux of capital now freed up to feed the cultural sentiments of the emerging world economies, the Chinese are buying art made by Chinese artists, the Latin Americans are buying Latin American artists, the Arabs Arab artists, and so on around the world. Most importantly, the markets aren't going indigenous under the banners of national supremacy or isolationism. Art made around the world--whether traditional or contemporary--raises both the cultural consciousness of people who had their cultural identities and arts repressed and stolen from them over the centuries, and the overall value of indigenous art on the global market today.

This accounts for the disappointment that arises among nationals when the opportunity to internationally promote their culture and artists is missed or diminished. The current controversy over the Syrian pavilion is a case in point. Not only is the Syrian Pavilion not curated by a Syrian (it was overseen and curated by three Italians), the majority of the artists are not Syrian. The Iraqi Pavilion curated by an American with Iraqis who live outside Iraq has also caused the consternation of Iraqis. Clearly, nationals whose artists lack the international exposure of the Americans, Europeans and Chinese feel cheated when their representation at the international bienniais is neither national nor culturally representative.

Clearly the process of selecting curators and artists to represent nations in Venice still has to be improved. But the expanding representation of post-colobial identity is encouraging enough to compel me to come around and agree with Bice Curiger's defense of the Venice Biennale's National Pavillions, at least for the time being. If we in the developed nations become so eager to import our idealization of cultural nomadism that we begin to zealously denounce the nationalism generating indigenous rediscovery, reclamation and celebration of lost identity and cultural pride, we would be no more enlightened in our imagined embrace of diversity than our forebears were in their pursuit of "Manifest Destiny" over the "noble savage." And, of course, reclamation of cultural identity doesn't mean that the call for national pavilions to be demolished should be permanently forestalled.

There is always the danger that cultural identity can harden into the kind of intransigent ideology that threatens cross-culturalization. Which is why the desire for a shifting nomadic criteria capacious enough to adapt to the diversity of the new international markets without the impediment of overtly ethnocentric values will always remain vital. I say "overtly" rather than "all" ethnocentrism because it seems dubious that a pure relativism can ever exist. We are, after all, residents of native cultures, though in the great urban centers of the world, our ethnocentrisms are becoming so porous as to be reaching the point of becoming mutable. With this in mind we should remember that nomadic appreciation of difference isn't intended to wipe out identity. It's meant to ensure that we possess reflexive minds capable of preventing cultural discourse and art from dissolving into narcissistic, authoritarian and myopic canons.

* The article I refer to here is "Going Back to Start, Perpetually: Playing the Nomadic Game in the Critical Reception of Art," Parkett #40/41, Zurich and New York, 1994.

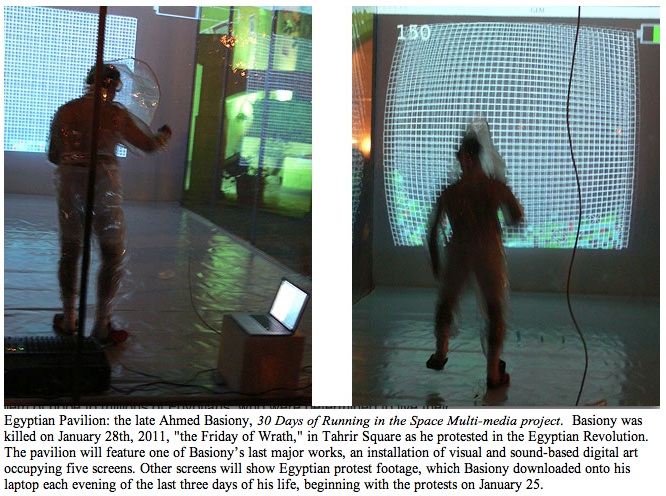

This post is dedicated to Egyptian artist Ahmed Basiony, who was scheduled to show his work in the Egyptian pavilion in Venice when he was killed on January 28th, 2011, "the Friday of Wrath," in Tahrir Square as he protested on behalf of the Egyptian Revolution. Although he has not lived to see his project through, his New Media environment has been installed in the Egyptian pavilion of the Venice Biennale as he planned it. In addition to the three photos above, the video below provides some representation of Basiony's installation and screenings at the Venice pavilion.

Work by Egyptian Artist Ahmed Basiony, assassinated in Tahir Square this January, comprises the participation of Egypt at the 54th Venice Biennale: An interview with commissioner Shady El Noshokaty and curator Aida Eltorie.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive