"SO?! How about the Lulu thing?" about 20 messages flashed insistently when I turned on my phone.

Thirty seconds on Twitter caught me up: Lululemon Athletica founder Dennis "Chip" Wilson had glibly explained away apparent issues with the company's legendary stretchy pants by locating the problems with women themselves, specifically those of us whose thighs rub together.

A chorus of angry journalists and turncoat "Luluheads" were already decrying Wilson on the Internet, but I was pinged for my thoughts for two reasons: one, because I study gender in American culture. Two, unlike most college professors, I also happen to have been a Lululemon ambassador.

Before I knew what I thought, I knew how I felt: angry.

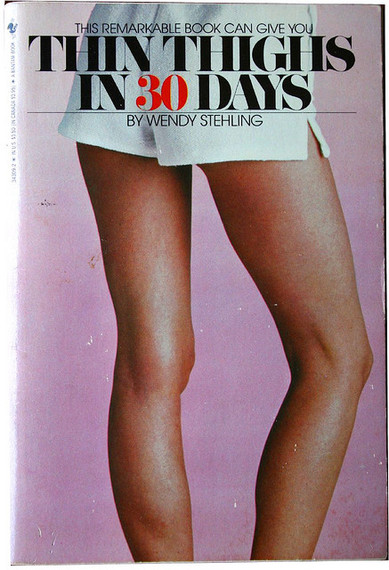

Wilson didn't just dismiss as unworthy consumers an entire group of women whose bodies don't conform to his ideal, he did it with galling insensitivity: by honing in on one of the most fraught areas on women's bodies. Thin Thighs in Thirty Days was released in 1982. Three decades later, in our age of the Spanx-made billionaire, the book still sells because we continue to vilify "thunder thighs," most obviously by our fetishization of the elusive "thigh gap" in online "thinspiration" communities.

Elsewhere, Wilson has raised ire for unapologetically disdaining the "mediocre" as beneath Lululemon's "culture of excellence." These comments are of a piece with his latest gaffe, in that our society often reflexively associates fat bodies with moral qualities such as laziness, complacency, and, yes, mediocrity. Wilson's implication that training our eyes on our thighs will cultivate excellence is preposterous, particularly when the damage wrought by constructing women's bodies as embodiments of self-worth is widely acknowledged, even as it is a timeworn tradition.

If you're reading this, you probably have some sense that the personal is political, so I'll just share that my own thighs touch. I've had two babies now, but my legs also met when I was a roly-poly baby myself, an elementary-schooler who felt chubby but in retrospect looked quite "normal," a teenager who wrote out her daily calories as dutifully as her French conjugations, a college student who sweated it out in Step aerobics fueled by the '90s "healthy" menu of fat-free fro yo and Diet Coke, and as an adult who ran two four-hour marathons. But here's the rub: my thighs also touched when I was enthusiastically invited to become a Lululemon ambassador in 2008.

And this is why I feel deeply disappointed.

Because my work in wellness, all of which emphasizes empowerment specifically around questions of body acceptance, has been strongly supported by Lululemon staff, almost all of them women.

The New York City team first approached me out of admiration for the principles of the physical practice I teach: self-acceptance, mindfulness, and body positivity. The fact that my full-time job was professor, not personal trainer? No problem: it only made me more inspiring to women carving out their own niche. That I was pregnant during my ambassador year? Fantastic! Schedule the photo shoot as late as possible, the managers suggested, in order to showcase a fit pregnancy. After my second child, two years later, Lulu sponsored my "Love Ur Body, Move Ur Body" workout events, occasions for women to exercise in clothing they had always shunned for fear of appearing physically inadequate. Most recently, Lululemon has supported my public-school wellness program HealthClass2.0, an initiative designed specifically to reframe the stigmatizing, obesity-centric discourse about health in under-resourced communities.

Capitalism is inherently patriarchal, feminist theory explains, and the examples above can easily be understood as benevolent paternalism: symbolic gestures that do little to disrupt underlying power hierarchies. This is probably true. Yet Lululemon's support of me and of my peculiar brand of fitness-activism was substantial and sincere enough for this feminist to make peace with the circumstance. And anyone who has happened upon a favorite yoga teacher at a free in-store class or who suddenly felt motivated to hit the gym a little harder thanks to a pretty pair of pants can attest to the fact that Lululemon's messages of empowerment can translate into genuinely inspired action.

I'm not one to be personally wounded by the actions of a corporation, no matter how loud its feel-good proclamations. For this reason, I haven't gotten too worked up about Lululemon's recent spate of scandals. Indeed, the "j'accuse" zeal with which many point out lululemon's corrupt "heart of darkness," often seems overblown; one part resentment of the company's massive success and another sanctimoniousness about how a "yoga company" should behave.

But there was one incident that resonates in light of Wilson's comments.

In 2010 I was flown to Vancouver to attend Lululemon's inaugural Global Ambassador Summit: three days of networking, exercise, and immersion in lululand. The organizers described it as an opportunity to "create awesome" and in many ways it was. At a roundtable discussion with a senior executive, however, I enthusiastically raised the idea of focusing more deliberately on pregnant women, whom I knew loved their clothes. The answer? A bemused snicker, and an explanation that Lululemon was about "aspirational fashion -- and there is NOTHING aspirational about pregnancy." I smiled weakly, astonished at the incongruence between this arrogance and the attitudes of the lulu team back in New York.

I immediately thought of this interaction when I heard Wilson's interview. That same macho derision toward female bodies, especially heavy ones. Most of all: a repugnantly familiar misogynist tendency to reduce a woman to her body parts. This cultural malaise reaches far beyond loudmouths at lululemon. The anti-choice movement is notorious for defining women as little more than uteruses. Ardent "lactivists" are guilty as well, disdaining women who choose not to breastfeed. Even the breast cancer awareness movement has embraced a do-it-for-the-boys campaign to "save second base." Wilson's comments, in correlating a woman's worthiness to wear lululemon with the distance between her thighs, (that's an inverse relationship, FYI) partake of the same disturbing trend.

So what does this mean? Sadly, for me it means I will be hanging up my Lulus once and for all. For all the genuinely positive energy that exists on Lulu's retail floors, an equally disturbing culture festers at the top and perpetuates a discourse with far more damaging implications than pilling capris. Wilson, in his "worst ever" apology video issued last week, surely got one thing right: angry customers should not be taking out their frustrations on store staff, many of whom I'm willing to bet are similarly repulsed by his comments. Rather, we should no longer be walking through those store doors at all.