Benjamin Grosser describes himself as a longtime heavy Facebook user. But a couple of years ago, he noticed some disconcerting patterns in how he was engaging with the platform.

"I would be more interested in how many likes something got, as opposed to who left the likes -- or how many comments I received, as opposed to what those comments were," Grosser told The Huffington Post. "I started to realize that I was focusing on the numbers themselves more than the content they represented."

Facebook's 1.3 billion global users post more than 3 million likes and comments each day, and tallying them up has arguably become as much of the Facebook experience as sharing content and engaging with others. And research shows we respond to the validating rush of a new Facebook "like" (or 20) -- when people gain positive feedback about themselves on Facebook, the brain's reward centers light up. The greater the intensity of the individual's Facebook use, the greater the reward. But heavy Facebook use is also associated with lower self-esteem and poor self-worth, indicating that the platform's "reward" doesn't necessarily lead to sustainable well-being.

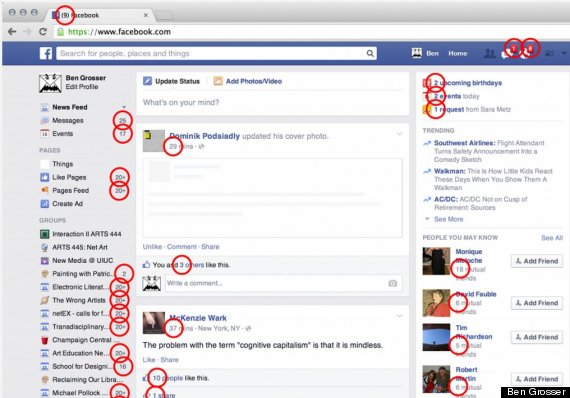

The many numbers of the Facebook interface.

Counting Facebook likes -- and taking them, on some level, as an indication of self-worth -- turns our basic drive for personal growth into a game of acquiring more and more markers of social status. This leads us to begin viewing ourselves and our friendships in quantitative terms, Grosser argues in a paper published this week in Computational Culture, a journal of software studies: How many friends do I have? How many people liked my post about my new job? How many people have "liked" this new product I'm thinking about buying?

Grosser, an artist and software developer, decided to investigate how Facebook's many numbers affect the way we all use the system -- and to see what would happen if he created a new version of Facebook without them.

So he created the Facebook Demetricator, an open-source web browser plug-in that removes all metrics from the Facebook interface. Users no longer see their number of friends or the likes received on a post (instead, it reads simply "people like this"). And there is no "+1" symbol from the "add friend" button.

"As an artist, one of the ways I ask questions... is to intervene within a system in order to examine how that system changes who we are and what we do," Grosser wrote.

The service, created in 2012, has since attracted thousands of users and plenty of media buzz. Grosser -- whose work has been referred to as “creative civil disobedience in the digital age" by Slate -- posited that Facebook encourages us to take part in a game of accumulating "social capital."

"When we are constantly being told how many friends we have, we are encouraged to add another, to make that number go higher, to exceed our current metrics," Grosser writes. "This is further reinforced by the interface, which places a '+1' in front of the 'Add Friend' button. The system makes it appear as if adding a friend increments one’s social capital by one."

Grosser's Demetricator plug-in removes the number of likes from the user's Facebook posts.

So far, the consensus among Demetricator users seems to be a relief at letting go of the need to check notifications and view Facebook as a competitive activity.

“Now it doesn’t matter to me how many likes something has," one user said in a comment cited in Grosser's paper, noting that he now pays more attention to the quality of the conversation.

"When you combine our need for personal worth with this constant conditioning to think of ourselves in quantitative terms, it starts to make us think about ourselves having to perform well," Grosser says. "By taking the numbers away... all of sudden people didn't feel as competitive."