If you were raised in the Seventh-day Adventist Church like I was then there is a strong possibility that you experienced some permutation of the following question, "Adventists... same as Mormons, right?"

Actually no, not even close. Adventists aren't really even first cousins of Mormons. Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are lovely people with many fine qualities but, aside from sharing a belief in the divinity of Christ and hyphens in our church's formal names Mormons and Adventists don't have much in common. Well, perhaps they have one more thing in common. They can both trace their historical origins to the teachings of men in early 19th century New York. The Mormons had Joseph Smith; Adventists had William Miller. So they aren't perfect cognates. William Miller did not proclaim himself a prophet but he did start a movement that would change religious history; first in America and then globally. Despite the similarities, American popular culture seems to be far less familiar with the man who got the ball rolling on the formation of the Seventh-day Adventist Faith.

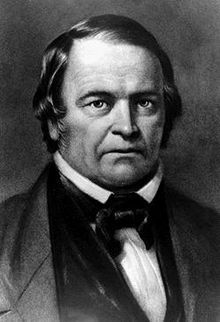

William Miller was born in 1782 in Massachusetts but moved as a small boy to Low Hampton, New York where he was raised in the Baptist faith. As a young man he had access to the private libraries of local politicians and was a voracious reader.

The War of 1812 found Miller working as a civil servant and a commissioned lieutenant in the Vermont militia. About this time, he came to the conclusion that he was no longer a believing Baptist but rather, a Deist, drawing inspiration from the writings of Voltaire and Hume. After he survived a particularly bloody skirmish at the Battle of Plattsburgh, he emerged from his military service with renewed faith and attributed his survival to Divine intervention.

Miller tried valiantly to reclaim his Baptist faith but his Deistic beliefs held sway. He tried to combine the two and speak publicly about Deism while still attending his local Baptist church. One day the pastor of the congregation was out of town and so Miller was asked to read the sermon. According to his own accounts, he had something of an epiphany at this time and became impressed by the compassion and goodness of the divine being who atoned for the sin of men. He converted wholeheartedly back to Christianity.

Miller's Deist friends were surprised by this turn of events and challenged him to make sense of the many inconsistencies in the Bible. Miller, ever the voracious reader and scholar, said if given time "I would harmonize all these apparent contradictions to my own satisfaction, or I will be a Deist still." Starting with Genesis and studying each verse of the Bible he arrived at two conclusions: Postmillennialism was not scriptural and that the time of Christ's Second Coming was revealed in Biblical prophecy.

Miller focused on what is known as the 2300-day prophecy. Basing his belief principally on Daniel 8:14: "Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed", he assumed that the "Cleansing of the Sanctuary" represented the Earth's purification by fire at Christ's Second Coming. Using the interpretive principle that a day in prophecy was equal to one calendar year and that the 2300-day period started with the decree to rebuild Jerusalem by Artaxerxes I of Persia in 457 BCE he surmised that this worldly era would come to an end in 1843. Miller wrote, "I was thus brought... to the solemn conclusion, that in about twenty-five years from that time 1818 all the affairs of our present state would be wound up."

It was not until August, 1831, when Miller preached in the small town of Dresden, New York, that he shared his ideas on the date of 1843. I must insert a personal side note at this point. According to my own family lore, my ancestors from neighboring Oswego attended this sermon and were converted to Miller's way of thinking at this very gathering.

From 1832 to 1834 Miller published letters and articles sharing his research. The interest in his theories became so overwhelming that he published a synopsis of his teachings in a 64-page tract entitled Evidence from Scripture and History of the Second Coming of Christ, about the Year 1844: Exhibited in a Course of Lectures.

With the publication of his work Miller was no longer a farmer living in obscurity. His writings had captivated so many that followers of his teachings were referred to collectively as the Millerites. If you lived in the United States in the 1840s you knew about them.

Then, along came Joshua Vaughn Himes, the pastor of Chardon Street Chapel in Boston. Joshua Vaughn Himes was a well-known publisher and while he may not have subscribed to Miller's ideas he saw their literary value. On February 28, 1840 he established a bi-weekly newspaper to publish them which he called Signs of the Times.

Despite the urging of his supporters, Miller never set an exact date for the Second Coming. He did narrow the time-period to sometime in the Jewish year beginning in the Gregorian year 1843, stating: "My principles in brief, are, that Jesus Christ will come again to this earth, cleanse, purify, and take possession of the same, with all the saints, sometime between March 21, 1843, and March 21, 1844."

When March 21, 1844, came and went he amended the date suggesting that April 18, 1844 could be the date based on the Karaite Jewish calendar as opposed to the Rabbinic. Again, April 18, 1844 came and went without incident and Miller responded publicly, writing, "I confess my error, and acknowledge my disappointment; yet I still believe that the day of the Lord is near, even at the door."

So while William Miller is often credited with arriving at the proposed date of the Second Coming, it was actually a man named Samuel S. Snow who set the date of the Lord's return. In August 1844, at a camp meeting in Exeter, New Hampshire, he presented a message that became known as the "seventh-month" message or the "true midnight cry." In a discussion based on scriptural typology, he presented his conclusion that Christ would return on October 22, 1844.

The fact that you are reading this article would indicate that the Second Coming didn't happen. October 22 would go on to be known as "The Great Disappointment", a somewhat unfortunate name as Bill Maher pointed out while talking about Dr. Ben Carson, a member of the Seventh-day Adventist faith, recently. He said of Carson's Adventist beliefs, "Do we really want a guy who is disappointed that the world didn't come to an end having his finger on the button?" One hundred and seventy-three years later, that interpretation of Scripture is a bit problematic for Adventists. But, on October 22 every year, my Adventist friends and I will jokingly wish each other a Happy Disappointment Day.

Miller lived five more years after the Great Disappointment and never gave up his belief in the imminent Second Coming of Christ.

Miller's followers would go on to found the Seventh-day Adventist Church. And while in his life he never called himself a Seventh-day Adventist nor even used the term his actions were the catalyst for the formation of a religion that now numbers over 18 million adherents worldwide. None of whom should be confused with Mormons. Adventism and Mormonism both trace their points of origin to American men in the 1840s but the similarities stop about there. So the next time you hear Mormons and Adventists being conflated into one group you can say, "Nope, Adventists are the result of that other farmer from upstate New York."