Here's one tried and tested way for a president to deal with a difficult Congress: Go to your private office on Capitol Hill and stay there until a deal is done.

Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president of the United States, lobbied Congress from his private room in the Capitol Building -- called the President's Room -- that has seldom been used in the nearly hundred years since and is now largely forgotten to history. One of Wilson's innovations that did stick was the State of the Union Address, which previously been a written address to Congress.

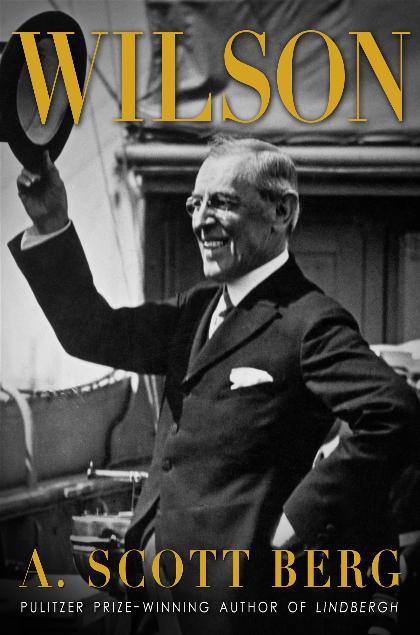

"Wilson wanted to put a face on the presidency," said A. Scott Berg, whose new biography Wilson is a comprehensive and deeply human portrait of the former president. "He wanted to Congress to see a person who has an agenda of ideas that they might enact together."

So alive is Berg's depiction of Wilson that Warner Brothers has already optioned the film rights as a starring vehicle for Leonardo DiCaprio.

Berg, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Lindbergh, his biography of aviator Charles Lindbergh, spoke with me recently by phone from an Amtrak train en route from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., to speak at the National Book Festival. Berg talked about his research, comparisons of Woodrow Wilson to President Obama, and Wilson's lessons for dealing with an obstinate Congress.

Did you start out to write a biography about Wilson, or did you happen into it?

He had been a great figure in my life growing up. I really admired him a lot as a teenager, and one of the reasons I went to Princeton was because that's where Woodrow Wilson had gone. Wilson has really been with me since I was a proper reader. All that time, I had an image developing of Wilson in my own mind, which I had never seen in another book. And that's ultimately the question a biographer asks before he falls off a cliff for -- in my case -- 13 years, which is: Do I have something new to say? And I felt I did.

I felt nobody had ever written a really emotional book about Woodrow Wilson. In part, because he was an academician himself, most of his biographers have been academics who have written, I felt, dusty books that never made him come alive. You get a lot of military history or diplomatic history or political history, but they never capture the personal history, which I felt informed every personal decision he ever made.

I wanted to write the most personal, humanizing biography of Wilson that I could -- especially humanizing because he is usually depicted as this very cold, dour Presbyterian minister's son, and he certainly had that streak within him. But he was a very full-bodied, red-blooded man. That's what I tried to capture in Wilson.

How did you know about Wilson growing up? I assume your formative reading years were in the 1960s?

That would be correct. I read a book called When the Cheering Stopped by Gene Smith, which was about Wilson's last few years. And it was really the first book to talk about the role the second Mrs. Wilson played after Wilson suffered the stroke, which was kept a dark secret from the world. I just remember reading that book and being hooked on him.

So at 15, which was in 1965, I really began reading a lot about Woodrow Wilson and books by Woodrow Wilson. By the time I went off to college at Princeton, Wilson was very much in my mind and in my life.

Did you always think you would write this book?

In the back of my mind I had always thought I might get to it, but I wasn't sure there would be an audience beyond me. Wilson has fallen into disfavor in the last few decades especially. After I finished "Lindbergh," I went to my editor and we discussed that I would do my memoir of Katherine Hepburn [Kate Remembered].

I went in to talk to my editor -- Phyllis Grann, to whom the book is dedicated in part -- and I said I wanted to do a Katherine Hepburn memoir that I had thought about for 20 years, and then we went through ideas for potential subjects. And I said, "Phyllis, you know, I must confess to you I have one secret idea I've been carrying around with me ever since I started writing, and that's Woodrow Wilson. She said, "Oh, I don't even need to discuss that. Done."

She asked how I ever got interested in Woodrow Wilson, and I told her when I was 15 I had read a book called When the Cheering Stopped. And she went very quiet and welled up a little. She said, "Scott, that's kind of amazing because in 1964 I was a secretary at William Morrow & Co., and my boss walked over to my desk and said 'Phyllis, I know you want to be an editor, so here's a manuscript. See what you can do with it." And it was When the Cheering Stopped.

Since you already knew a good bit about Wilson, how did you start with this book?

I've been reading about Wilson for 40 years, so I had a lot of material under my belt. Starting in 2000, I sat down with his papers and began to go through them. I had a great stroke of fortune, which was a Princeton professor named Arthur Link, who spent 40 years of his life collecting all of the Wilson papers he could possibly find, and he printed Wilson's greatest hits in 69 volumes. I bought a set of those books so I could work from home, then I visited libraries like the Library of Congress and the Princeton Library to go through the papers left out of the 69 volumes, and then traveled around to some other libraries.

In the last five or six years, two really important caches of personal papers surfaced -- one being a couple of trunks of papers belonging to one of Wilson's daughters, and the other being papers that belonged Woodrow Wilson's personal physician and really most loyal friend, Dr. Cary Grayson. I had access to those that nobody else had.

I took notes for eight years, six months to sift through and sort it all out, and then about five years to write it.

For the op-ed that you wrote earlier this year in the New York Times about Wilson and Obama, did the Times come to you and say they wanted a history lesson for President Obama?

No, I went to them, actually, around January and said, "March 4, 2013, will be the 100th anniversary of Wilson's inauguration. I would really like to write a piece to remind people that -- A -- Woodrow Wilson existed and was important and governed in a brand new way, and -- B -- I think I could really contemporize this story and really make it reverberate by writing a kind of open letter to President Obama."

It was partly historical and partly editorial. It was basically: Obama, take a few pages out of the Wilson playbook. Look at the way he legislated. Show up in Congress more. Sit in the President's Room [in Congress], which no president has really done since Woodrow Wilson. Co-operate the government the way Wilson did with the legislature.

Did Wilson reinvent the State of the Union address as a lobbying tool?

Less for lobbying, though that's why he sat in the President's Room day after day. It was mostly that he wanted to humanize, to personalize, the institution of the presidency. He believed governments were not just institutions but the people who worked in them. It's what he used to say about industry: There aren't corrupt corporations; just corrupt people who work within corporations.

You've been on the road a lot already for the book. Are you more promoting the book or promoting Wilson?

I'm sort of on a mission to reinstate people in Woodrow Wilson's minds. I don't mind so much if people love or hate Wilson, but I want them to be informed about Wilson. Until a few decades ago, he was always in the top four or five of the great presidents. Now, most people under 50 don't have a clue who he is.

This is a man whose ideals are so much with us today. When Barack Obama gave his speech about Syria [on September 10, 2013], that whole speech was pure Woodrow Wilson. When he asked: Are we supposed to be the policemen of the world? When he asked: Can we just stand by while someone is gassing a thousand of his own people, killing children? Can the United States morally stand there and do nothing? Those were the very questions Woodrow Wilson posed on April 2, 1917, when he said the world must be made safe for democracy.

It's not just foreign affairs. Our economy is built on Woodrow Wilson's ideas and principles -- the Federal Reserve System, the modern income tax, the eight-hour work day, workers' compensation. That's all Wilson.

If you take Wilson's eight years in office and divide that into four congressional terms, did he have an agreeable Congress throughout those terms?

No. The trajectory was a downhill slide. He started big. In the second, he still had a Democratic majority. By his third Congress, things were pretty even. By the fourth, the Republicans were taking over. By the time he left office, a Republican landslide replaced him. [President] Warren Harding and Congress began to undo as much of Woodrow Wilson as they possibly could.

That happened to Johnson, to Clinton, and to Obama. Is there something built into the system that favors the challenging party?

I think it's sort of the pendulum theory. Pendulums can only swing so far. When you look at the presidents you named - Johnson, Clinton, Obama - who came in like a house on fire and did as much business as they could. Republican's say, "Let's slow this down." And then Congress become increasingly Republican. And then the pendulum swings back.

What's the causation link? Is the president caught in an up-and-down wharp, or is it a response to the president?

Progress is generally incremental. Woodrow said the country is not really Republican or Democratic. There's a big independent middle. Republicans and Democrats on either side are trying to move that big independent middle in one direction or the other. I think that's why there can only be incremental progress. Periodically, a great progressive leader will push things one way, or a conservative will come along -- Reagan -- and push things the other way. But the public at large only wants so much change at a time. I think the only exceptions to that are times of extreme crisis such as a Great Depression or a war when the public is less inclined to change leaders mid-stream and really wants the leader to carry on with the full support of the country.

Do you see Obama's presidency as far as the relationship of the three branches of government being analogous to Wilson or any other president?

I don't think [Obama] exerts the power or the skill that Wilson did in working with the Legislative Branch. That said, Obama has been extremely effective when you start to tally up the legislation that has gone through during his administration. It's pretty remarkable considering the contentiousness in Washington.

Did Wilson deal with that?

Oh, my God! You've got to get to the end of the book! You will see [Wilson] fighting with Henry Cabot Lodge -- especially over the League of Nations -- which literally killed Woodrow Wilson. Lodge was so hostile that Wilson felt he had to take his show on the road. He went on a 29-city tour for, I think, the greatest cause a president has ever fought for, and collapsed in the middle. None of that that would have happened if Henry Cabot Lodge and Woodrow had said down at a table and hashed things out.

The enmity was so great between them that when Woodrow Wilson died and Henry Cabot Lodge was going to show up for the state funeral as the leader of the Senate, Mrs. Wilson wrote him a note that said, "Please don't show up." And he didn't.

Did you read John Milton Cooper's Woodrow Wilson: A Biography?

I didn't read it. I didn't want to be influenced in any way or have anyone think I had been influenced in any way. I will confess I always had what I thought was a great beginning and end for my book. So when his book came out [in 2009], I went to a bookstore and read the two opening pages and two closing pages just to make sure my opening and closing were not the same thing, and mine were far from it.

Did you decide at some point that Wilson would be a single volume?

I decided at the beginning. There are several multi-volume [Wilson biographies], and that's the last thing I wanted to do. I wanted to write a readable but historical biography of Woodrow Wilson, and I really tried to write it in a style unlike any other biography of Wilson. I wanted to write a page-turner, and I think it is.

Scott Porch is an attorney and writer in Savannah, Georgia. He is writing a book about the historical impact of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.